Sculpture is at the core of Pedro Reyes’ work. Though much of what the Mexican artist creates is outside the realm of traditional sculptural practice, he nonetheless describes his work as “social sculpture”. Using performance, participation, and installation, Reyes’ work is recognisable for the playful and humorous approach he takes in addressing global sociopolitical issues, from gun culture and nuclear armaments to staging the experimental People’s United Nations conference in 2013. Alongside this collaborative art practice, Reyes is also interested in investigating histories of art. This aspect of his work is what he describes to Present Space as a “more classical” form of sculpture.

In recent years, his art practice has been informed by sculpture and printmaking—used by Reyes to explore traditional methods of art making that date back to Mesoamerican civilisations—as well as by the emergence of a new art style in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution in the early twentieth century. After the revolution, artists turned away from the European canon to instead focus on the rich histories of art making that existed in Mexico. As Reyes explains, “Artists looked [at] what was right below their feet, acknowledging that there was an art history buried that was as important as any other in the world. When you’re coming out of a colonial period, you need to establish your identity as a country. And what Mexican artists did was to go to the ancient past and to the popular crafts to tell the story of the Mexican Revolution”.

Muralists such as Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siquerios are well known outside of Mexico, but other visual arts that were instrumental in the Mexican Renaissance, like sculpture, are less remarked upon. “The sculpture of the ’30s and ’40s was called civic sculpture,” Reyes says—monumental sculpture intended to “reach mass audiences and inhabit public spaces”. This is evident in the work of sculptors such as Oliverio Martínez, who made four sculptures for the Monument to the Revolution, a 67-metre victory arch designed by Carlos Obregón Santacilia in Mexico City. At each corner of the monument, a sculptural grouping depicts different aspects of post-revolutionary Mexico: independence, reform, agrarian and labour laws. More than 11 metres high, these monumental carvings evoke precisely the ways in which sculpture can be used to establish identity and belonging in public spaces.

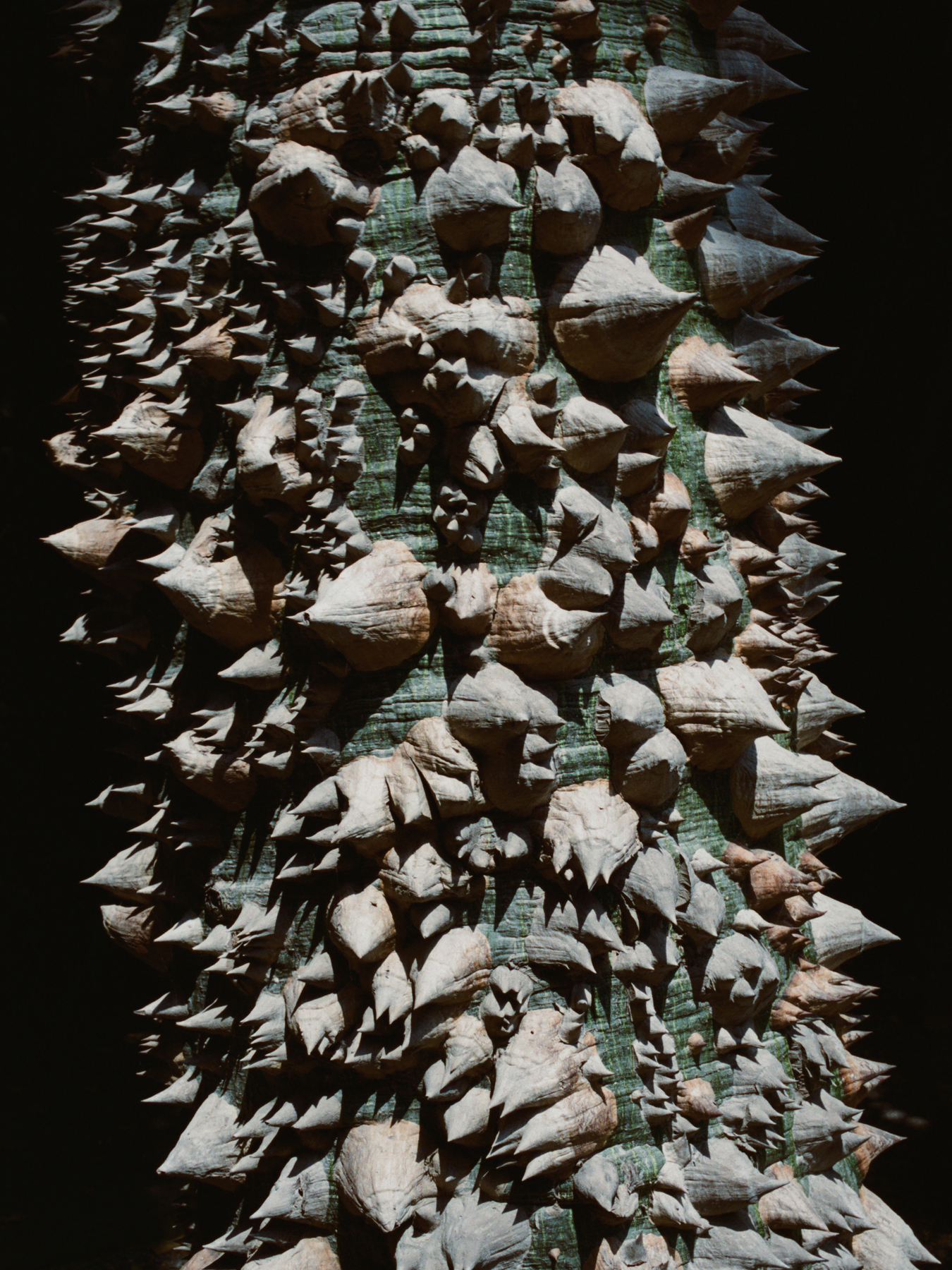

In 2022, Reyes unveiled Citlali, a large-scale direct carving in stone sculpture that was commissioned for the San Antonio River Walk in Texas. The work’s name, which means “star” in the indigenous Nahuatl language, makes reference to the first civilisations in what is now San Antonio, and thus evokes the ways in which monumental sculpture was used in the twentieth century to consider topics such as identity on a large scale.

Reyes has also turned to monumental sculpture in art settings, including an exhibition of his work staged by the Lisson Gallery in Los Angeles in the summer of 2023. Here, his work probed the notion of “monumental”, as both a formal quality and a vehicle for communicating sociopolitical ideas. For instance, hands—which are a recurring symbol in Reyes’ work—are a motif used also by Martínez. His depiction of labour laws, for example, is two workers shaking hands, with one’s hand resting on the shoulder of his compatriot.

In The Treaty (2023), a sculpture carved in volcanic stone by Reyes for the exhibition, the hands of two elongated arms meet in a similar embrace, a depiction of solidarity and comradeship. As Reyes explained in a video for the exhibition, “I like that there is the union of two in the same level—an agreement; there are two elements carved out of the same block.” In Detente (2023), a marble hand doubles as a dove, from the Corbusien notion of open hand as symbol of peace and reconciliation. As such, the hand here reflects Reyes’ long-standing pacifism while acknowledging the work—social, political, physical—it demands.

Even though Reyes describes this aspect of his practice as “classical sculptural”, the social message is never far from the surface. His use of traditional stone-carving methods that date back thousands of years ties into exploring ancient Mesoamerican practice. Reyes learned how to carve directly into stone in order to both understand the tradition and keep it alive. “Most stone carving today is all by robots, and a robot may actually do the same work that I do 50 times faster. Sometimes I ask myself, ‘Why am I doing it by hand?’” But the process ties into the artist’s exploration of national identity and how artists after the revolution looked to pre-colonial traditions.

Around the time of the Mexican Renaissance, Reyes says, there was “something called the school of open-air sculpture, where people would learn the trade and then participate in the making of public commissions”. It’s for that reason Reyes treats his own studio like something of a school, in which apprentices are taught by artisans to carve stone before going on to work as studio assistants. By not giving in to robots, Reyes hopes to preserve an “intergenerational transmission of knowledge that otherwise will be lost. The idea being to bridge different moments in history, instead of trying to be on the forefront of technology. We are trying to keep ways of working alive that resist the passage of time”.

While Reyes’ investigation of traditional sculpting methods is a more recent component of his art practice, the participatory nature of opening his studio to skilled artisans and apprentices links to ideas that underpin the social aspect of his work. Reyes has long worked with institutions and government bodies to both raise awareness of and directly work towards disarmament in Mexico. This was first undertaken in 2007 as part of the ongoing series Palas por Pistolas, for which Reyes worked with the Botanical Garden in the city of Culiacán to organise an arms exchange scheme that invited people to trade weapons for household appliances. The 1,527 weapons retrieved were melted down and fabricated into 1,527 shovels to plant 1,527 trees. In a later iteration, Disarm (2012), Reyes worked with the Mexican government to transform over 6,000 parts from confiscated firearms into 50 mechanised musical instruments.

More recently, Reyes worked with the organisation New Mexicans to Prevent Gun Violence (NMPGV) to repurpose firearms into flower vases, as part of a 2022 exhibition at SITE Santa Fe. Similar to how he disseminates knowledge by teaching direct stone carving, the NMPGV project enlisted high school students and taught them how to weld firearms into new forms. In turn, profits from the sale of the vases were converted to gift cards that NMPGV uses for a gun-buyback scheme. Reyes says, “We have created a sort of circuit where the gun vases effectively remove guns from the streets”.

Such projects rely on close, collaborative work. “It would be impossible for me to do it alone”, says Reyes. “The best collaboration often happens when everyone is at the service of a cause. Art is a very important way to give shape and form to urgent problems that we may not pay attention to, and every artist can bring to the table their own way of putting the message across”.

Art as activism is something that informs much of Reyes’ work. In November 2023, for example, Reyes took part in Artists Against The Bomb, an exhibition held in New York concurrently at the United Nations Headquarters and the Donald Judd Foundation. It was not an exhibition of his own work, per se, but one that Reyes had organised and that showcased almost 200 posters, some historic and some contemporary, against nuclear weapons. “The nice thing”, he says, “is I’ve also got some of the artists involved to nominate other artists, so it’s kind of like a group show where the artists are also co-creators”. In this way, it’s something of a “solidarity network” for raising awareness of the aims of the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

Besides the sculptor’s studio, the lounge features a vast double-height library space, where the uppermost nooks are accessed by cantilevered concrete steps. These shelves contain 30,000 books, records, movies, and artworks that have become part of a lending library. The initiative began in 2021 as an Instagram account with the handle @tlacuilobiblioteca, where followers could see which books Reyes had available to borrow. At the time of writing, the account had over 22,000 followers, and Reyes said it has a “community of 500 regular users; everyday someone rings our door and comes into the library and takes books, and then they bring them [back] two or three months later”. The project also has an outpost at the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil in Mexico City.

Reyes explains the concept for Tlacuilo: “We have this motto that ‘mi cosa es tu cosa’ [my thing is your thing], which is to expropriate your goods for them to become part of the commons. It is a bit aligned with ideas from communism and anarchism, which is to work through direct action and mutual support by administering our objects for everyone to access and enjoy”. The initiative also stems from the notion that, while a book might exist on “your bookshelf for fifty years, it is in your hands for probably fifty minutes. All the time that it’s sitting on the shelf, it could be accessible to other people”.

This notion is especially relevant when you consider the kinds of books that Reyes has in his collection, many of which are specialised, out of print, or unlikely to be digitised and online. It allows those with niche interests to access equally niche resources. Reyes notes, “It’s a little bit strange that every time I go down to the living room, there’s someone that I don’t know there, and I don’t always have the time to chat!” But, he adds, “it’s nice that all these books are in circulation because, in general, I think that there is sort of vicarious joy in finding that you’re not alone in these interests. And that every time you talk with someone [who shares these interests], your mind grows”.

The lending library fits neatly within Reyes’ notion of social sculpture, the material of which he describes as “interpersonal relationships, which are a very real substance and can be sculpted and exist in the world”. The core ingredients of this type of sculpture consist of “different moving parts that are a mix of different organisations and institutions collaborating”. Sculpture, he says, “is about changing the shape of things”.