Legend has it that Frederic Remington smeared his football jersey with blood from his local butcher before a game, to make it “more business-like.” Before gaining fame for his depictions of the American West, the portly painter was a rusher for Yale University from 1878 to ’79, during the sport’s brutal infancy, before it had shed the influence of English rugby and codified its own rules. The uniform Remington thus adorned consisted of a form-fitting long-sleeved shirt suggestively laced down the front and baggy taupe trousers cinched around the calves so that they billowed over the knees.

Early football was considered a warlike contest for otherwise well-behaved gentlemen. The first teams were fielded by Ivy League universities. From the start, reformers decried the sport’s sheer violence. There were often casualties. In 1904, an especially gory year, the battlefield claimed the lives of eighteen players. But so be it. Long out of the game by then, Remington said in 1894 that he hoped changes to the rules for safety’s sake wouldn’t rob football of its masculine power and hero-making potential. Football, like war and like the frontier, turned boys into men, and men into legends. A political cartoon from 1906 imagines what a “friendlier” game would look like: two players face off in pale blue and pink waistcoats and high heels, ribbons fluttering on their ankles.

Illustrating “cowboys and Indians” and the US Army for East Coast magazines made Remington his money and his reputation. But he also painted football, including thumbnails of the 1893 Yale team for Harper’s Weekly. (One panel shows a player naked from behind, being rubbed down by two team therapists.) The sport was an enduring inspiration for Remington. The frantic energy of one of his best-known and oft-imitated paintings, A Dash for the Timber (1889), evokes the charge of a defensive line—eight riders abreast, running and gunning for their lives, coming—dramatically, sensationally—straight for the viewer. It’s the kind of thing Remington wouldn’t have witnessed on assignment for Harper’s Weekly, certainly not from that risky angle (not least because he tended to avoid situations where bullets flew). But you can sense the energy of what he must have experienced from his crouch on the collegiate gridiron. Another engraving of 1893 depicts an offensive rush in a chaotic composition that closely presages Remington’s 1909 painting of the US calvary’s Rough Riders blitzing San Juan Hill.

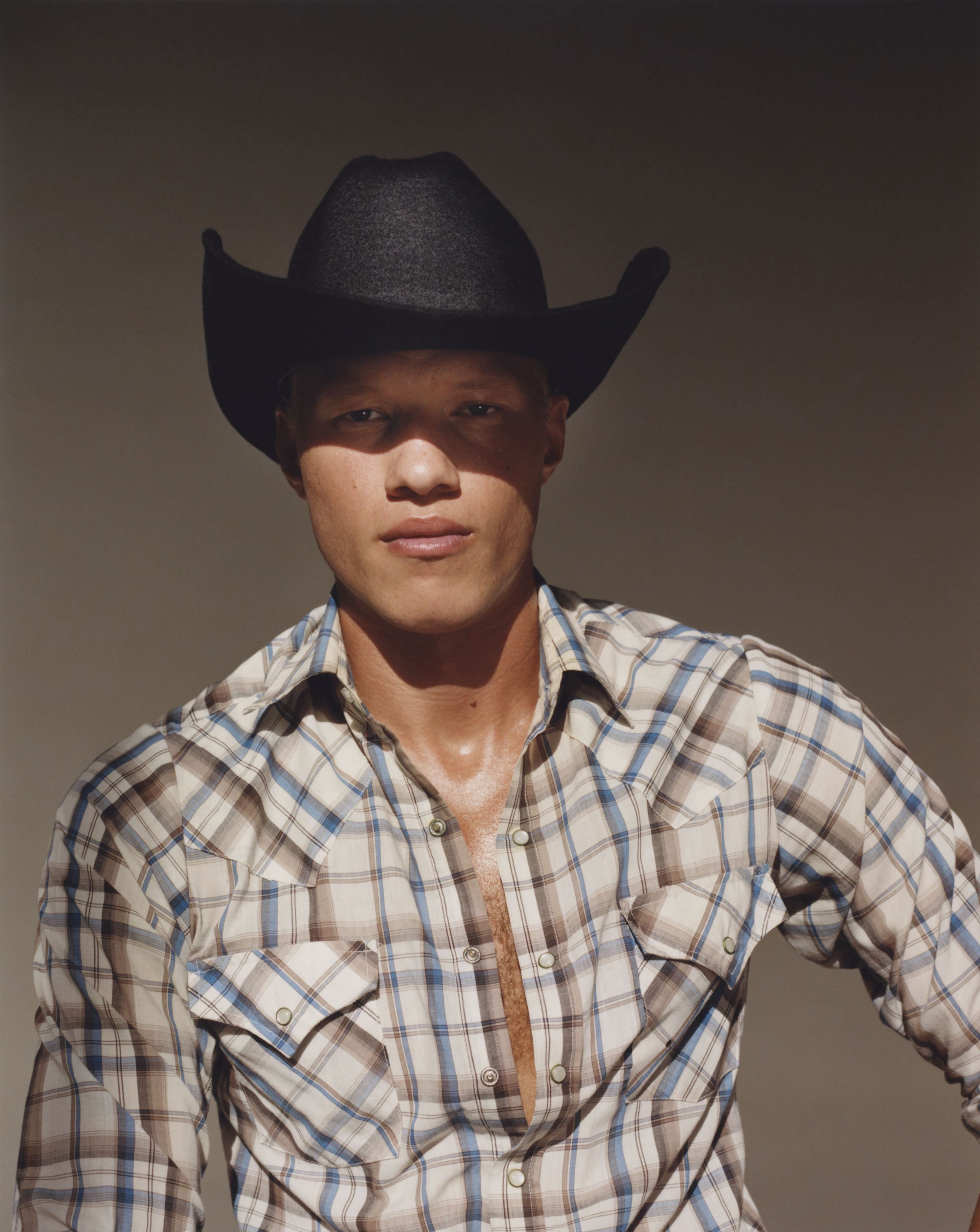

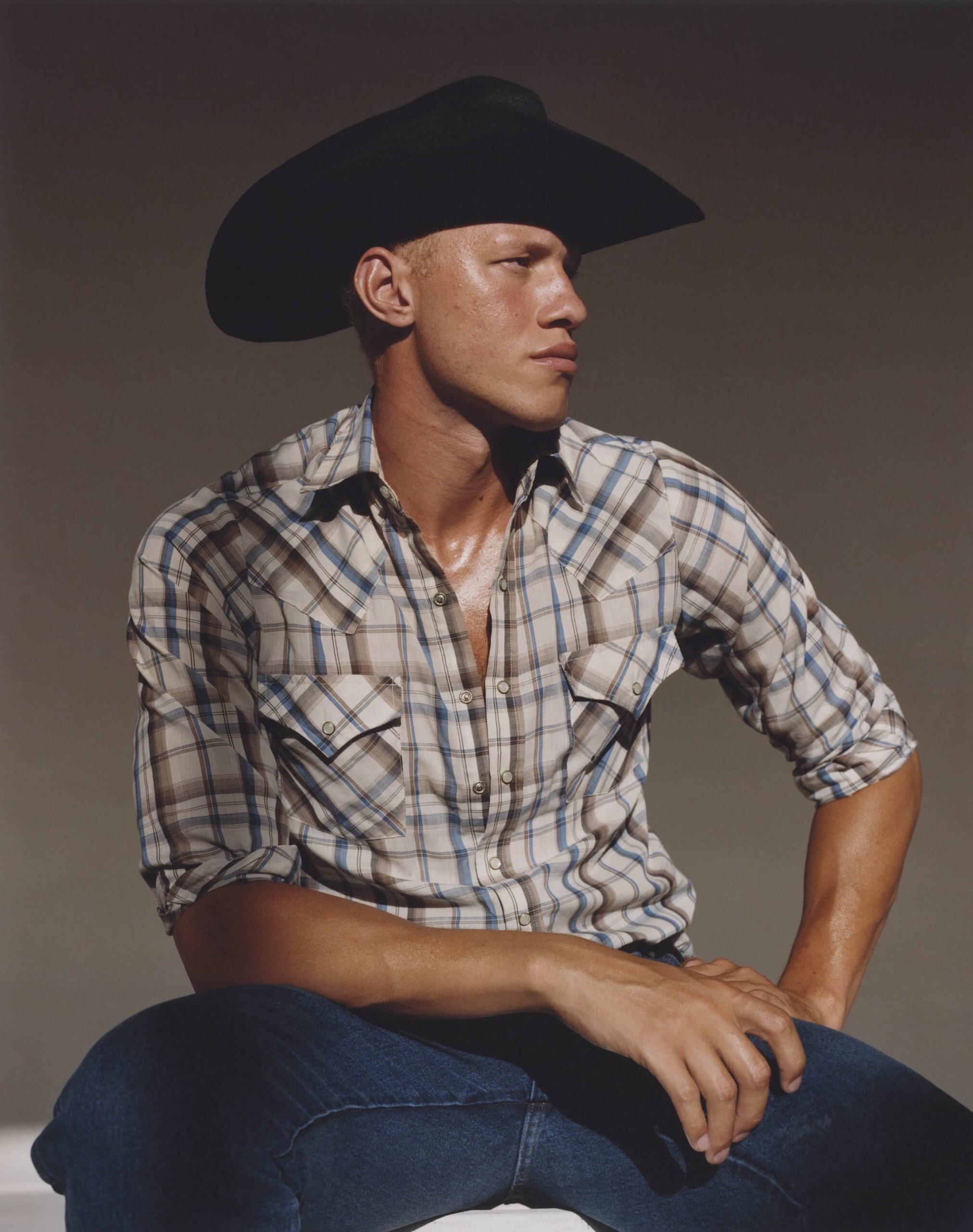

As he saw more actual battles, Remington grew disillusioned with the military. His experience of inglorious carnage in the Spanish American War left him nonplussed (he complained that the calvary barely rode horses) and the massacre of women and children at Wounded Knee turned his stomach. (Football was an abstraction of combat—that was better.) Out West, the painter registered the denouement of another manly, heroic sphere. Cattle ranching was becoming more sedentary as barbed-wire fences sliced up the prairie. A practically mournful canvas from 1895, The Fall of the Cowboy, shows a pair of roughnecks in the snow; one has dismounted to open a gate.

The mythical paradigm of manly struggle was hard to maintain as the frontier closed. Remington’s late style circa 1900, influenced by the Impressionists, is relatively misty and soft, as if acknowledging he was depicting not the actual American West but merely a dream of it. Where his past battle scenes were jagged and exciting, now the dead rested smooth on the plains. It was largely this transformation into myth that allowed the cowboy to transcend his or her unwashed reality and become a sex symbol. Western films and television in the early twentieth century wholly created the idea of the desirable loner, riding into a wild sunset after setting things right in town. In fact, cowboys usually travelled in pairs larger groups, keeping watch and keeping warm in one another’ bunks. To maintain the masculine ideal, the fantasy must be kep s far as possible from its origins—football from blood and death, cowboys from sheep shit.

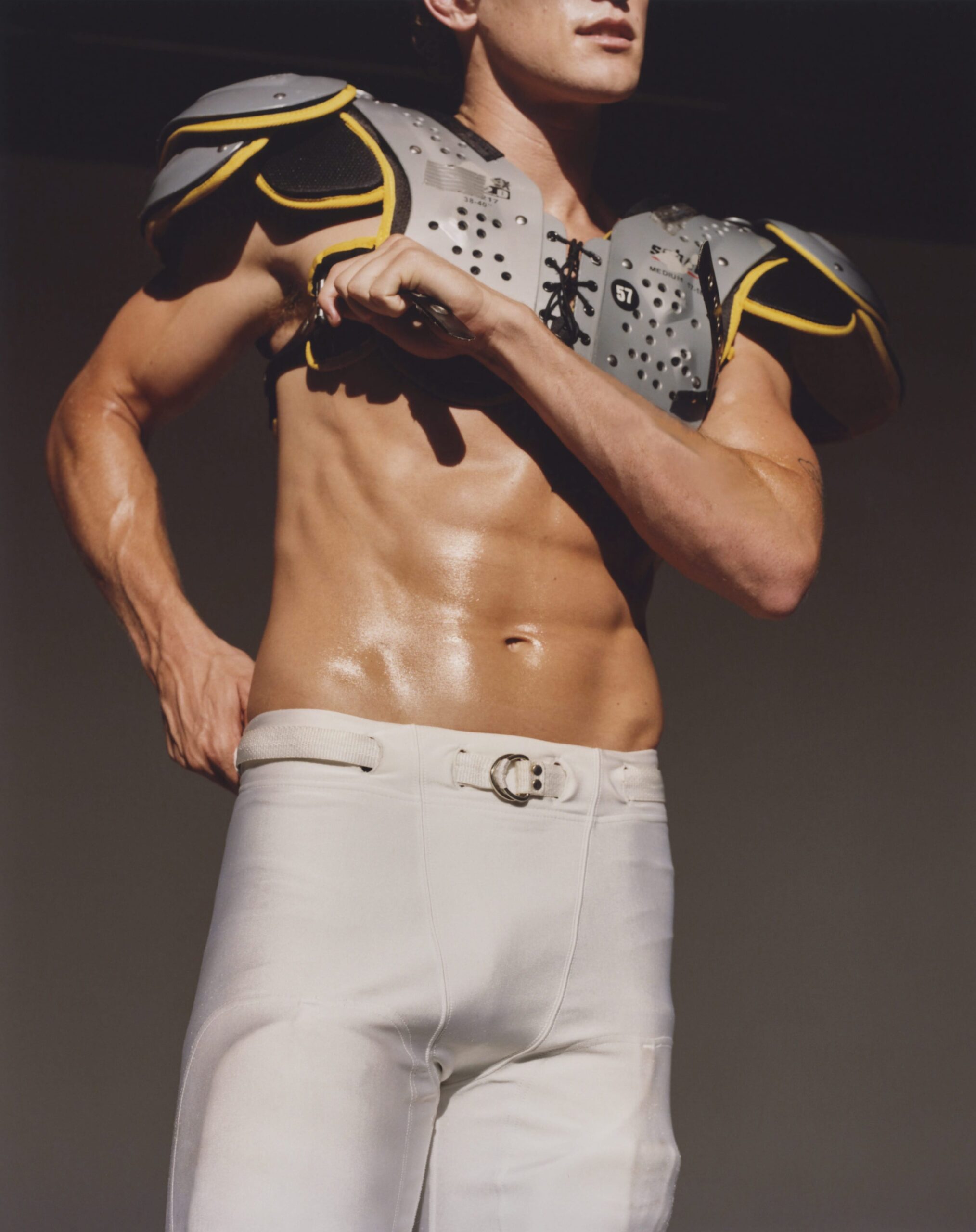

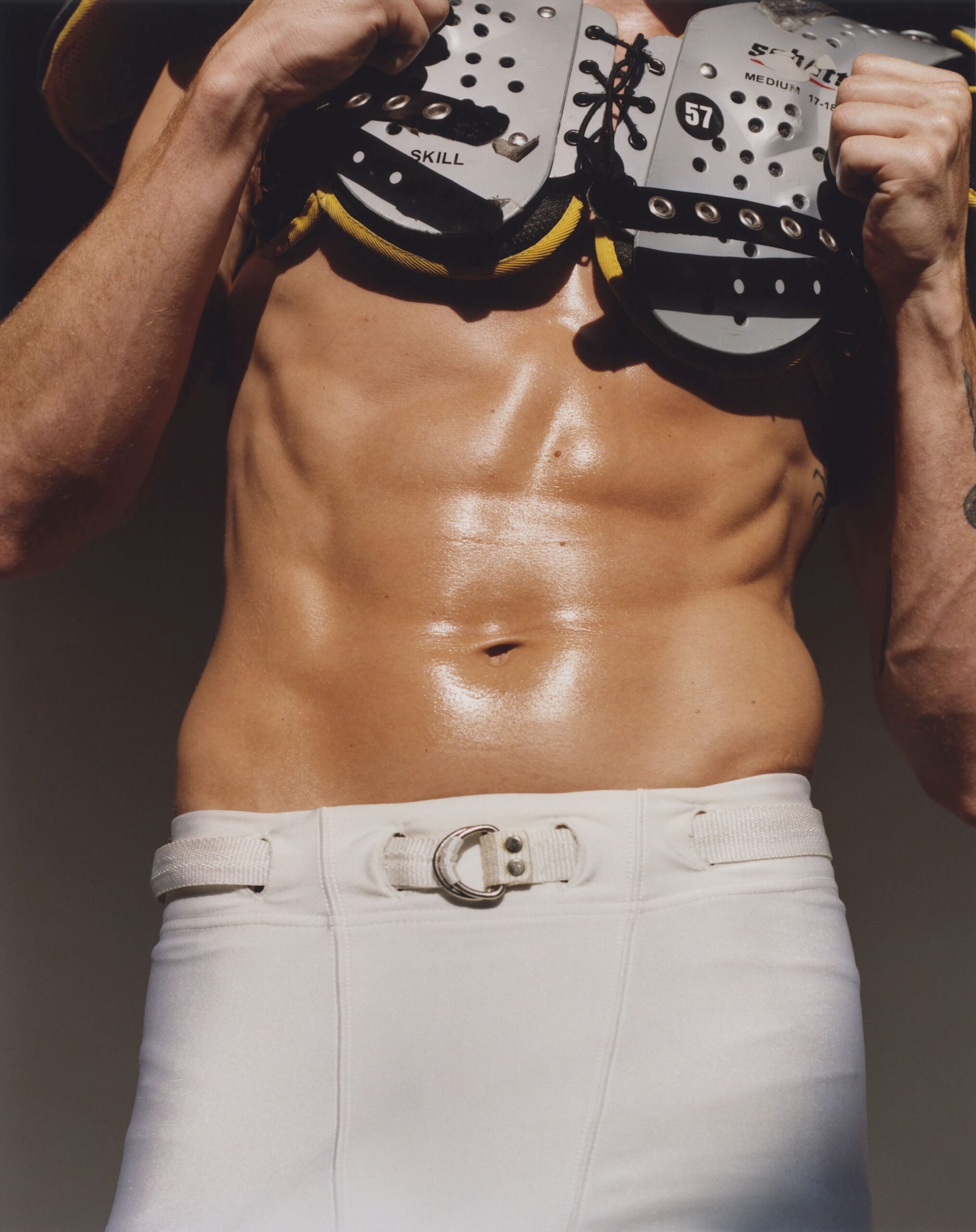

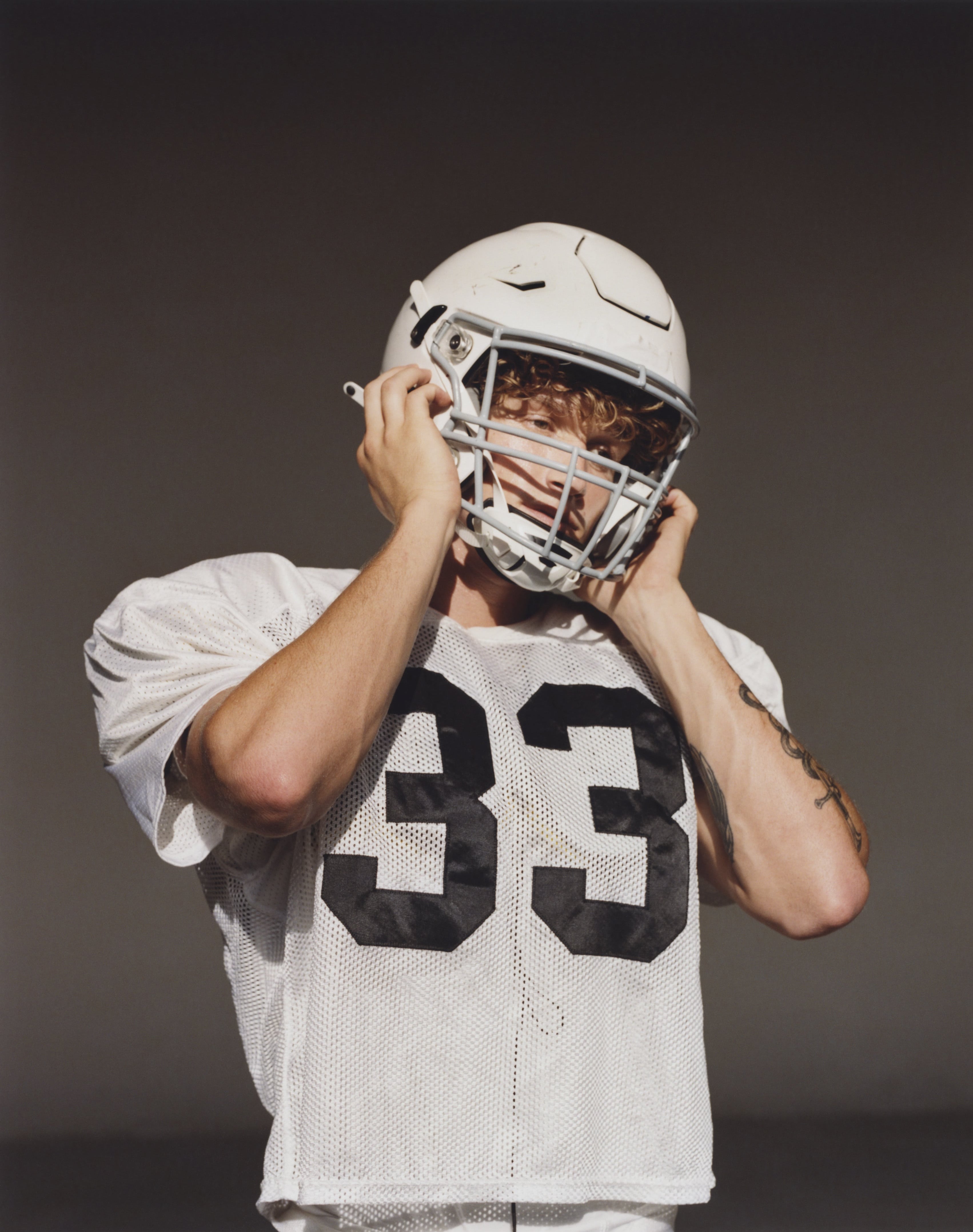

Of course, these abstract fashions are open to que r desire, too, and conservatives must spend significant energy asserting the straightness of masculine style. This is no easy task, since to certain minds even the notion of style puts one’s “manhood” in question. For J.C. Leyendecker, a prominent illustrator of the early twentieth century, football also provided a compelling outlet. Posters and magazines of the day often boosted sales with pictures of pretty girls admiring handsome quarterbacks. But Leyendecker shifted the scope of desire, making his players not just the love objects of society girls but also of other men.

One magazine cover for Collier’s from 1916 features a gargantuan player likely ready to throttle Germans in their trenches; his ripped jersey exposes a padded shoulder like a peek of negligée. In a series of ads Leyendecker produced for an overcoat company in 1919, the well-dressed male models admire geared-up football players—not vice versa.

Meanwhile, out West, as hired hands were recast as beefcakes, the rugged blue jeans worn for decades by miners and ranchers became more form-fitting. Countercultural figures, from beatniks to bikers, adopted jeans too, as a rebellion against the grey flannel suits like those Leyendecker’s clients sold. Accordingly, mainstream anxiety towards a brewing youthquake, represented by jeans sometimes snug enough to display a man’s equipment, manifested in hunts for both communists and homosexuals—a red scare and a lavender panic—two “un-American” types. Within photography, “to objectify the body is to fem nize it,” writes Patricia Vettel-Becker in her 2005 book Shooting from the Hip—an observation germane to Remington-style illustration. “Consequently, the male body must be inscribed within ritual frameworks of masculine-coded violence, such as war, sports, crime, gunfighting.” These “manly” contests legitimise the male-on-male gaze. Yet queer desire remains a constant worry—as mid-century “physique” magazines bear out. The inability to discern, once and for all, someone’s sexuality based on exterior signals has long haunted certain conservatives. This is precisely why one of the most nuanced mainstream gay love stories of our era, Brokeback Mountain, set during a sheep drive in 1963, caused such consternation: if two apparently manly-looking cowboys can be queer, who can’t?

By the 1950s the football uniform had taken its modern shape: shoulder-amplifying, hip-hugging, crotch-guarding. It’s no coincidence that in 1960, as Levi’s crossed into androgyny, a new NFL franchise in Dallas, Texas was branded the “Cowboys”—nor that a decade later the Cowboys began fielding what is indisputably the most pornographic cheerleading squad in the league. With comely co-eds waiting in the endzone, we know what the goal really is. To this day, only one openly gay player, Carl Nassib, has taken the field during an NFL season. Perhaps Remington got his wish—football remains one of the last proud pantomimes of straight masculinity—but you have to wonder who they’re fooling.