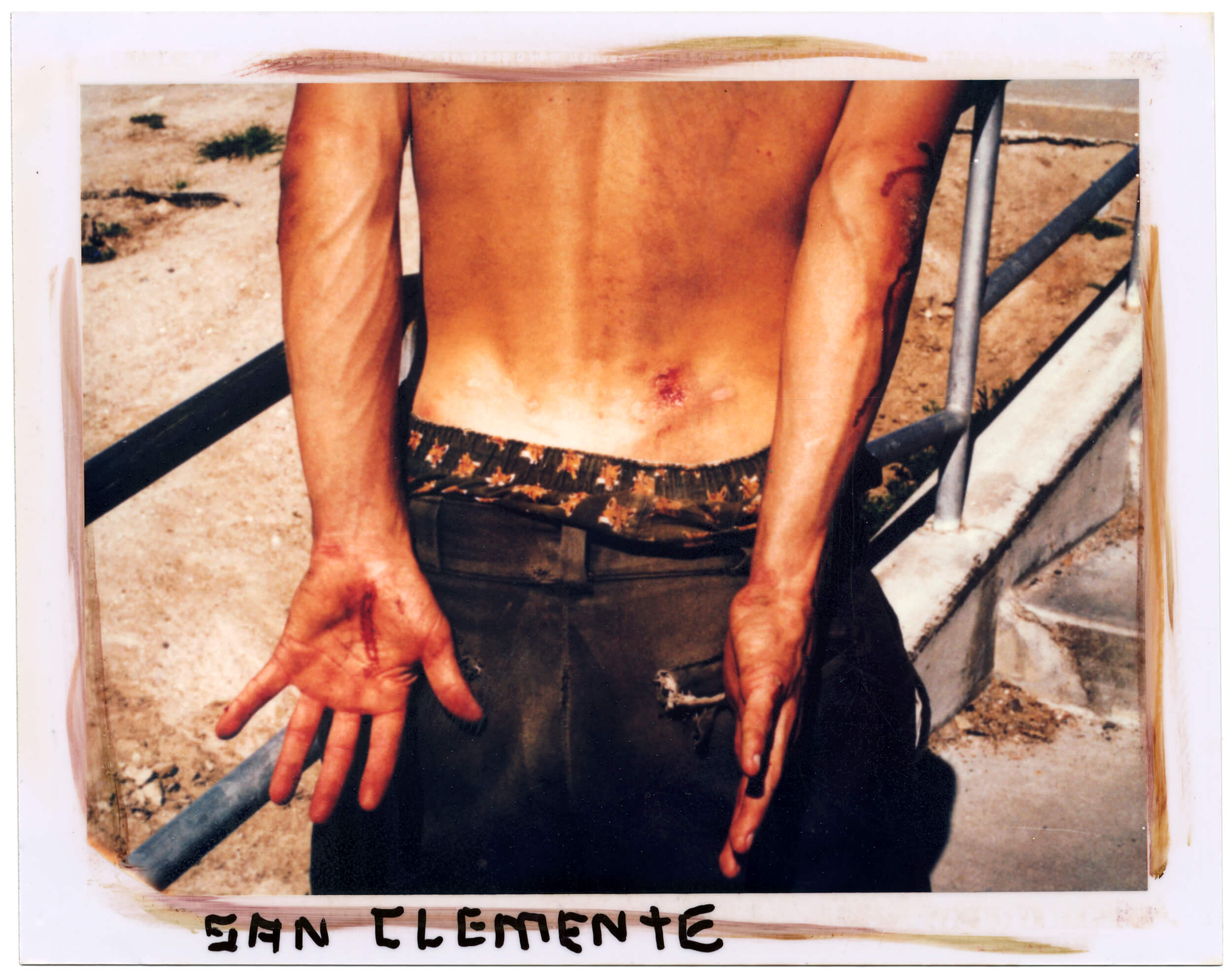

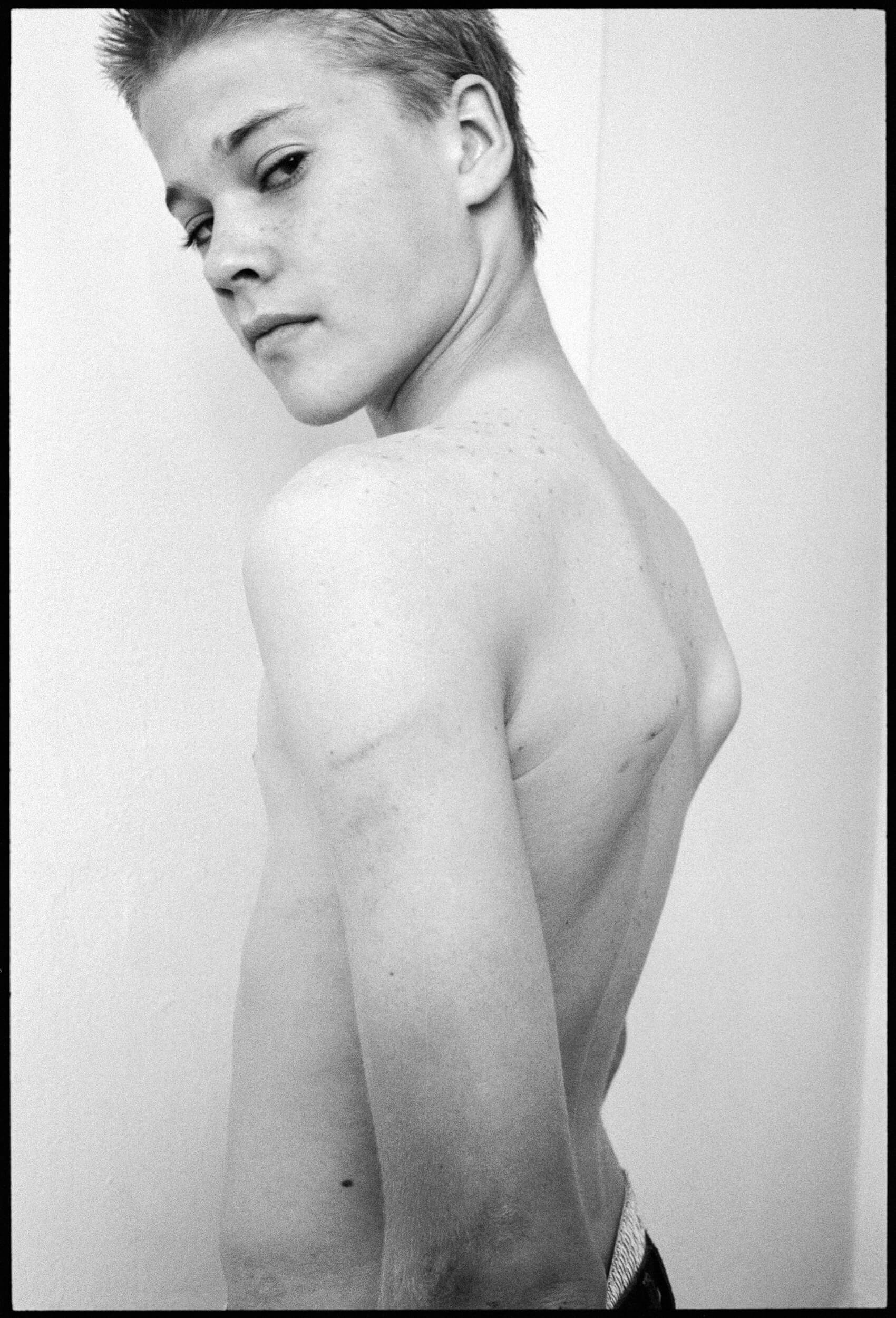

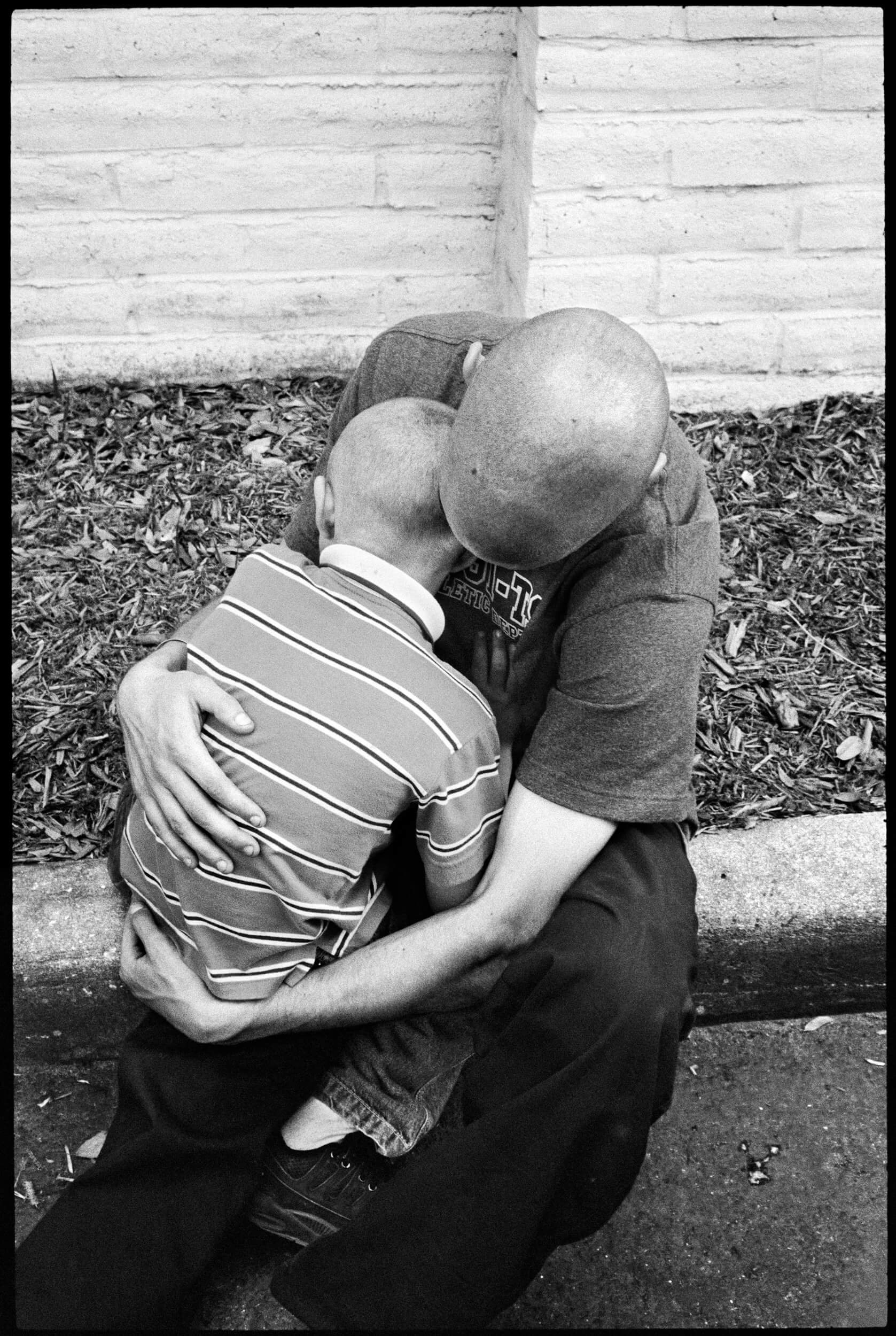

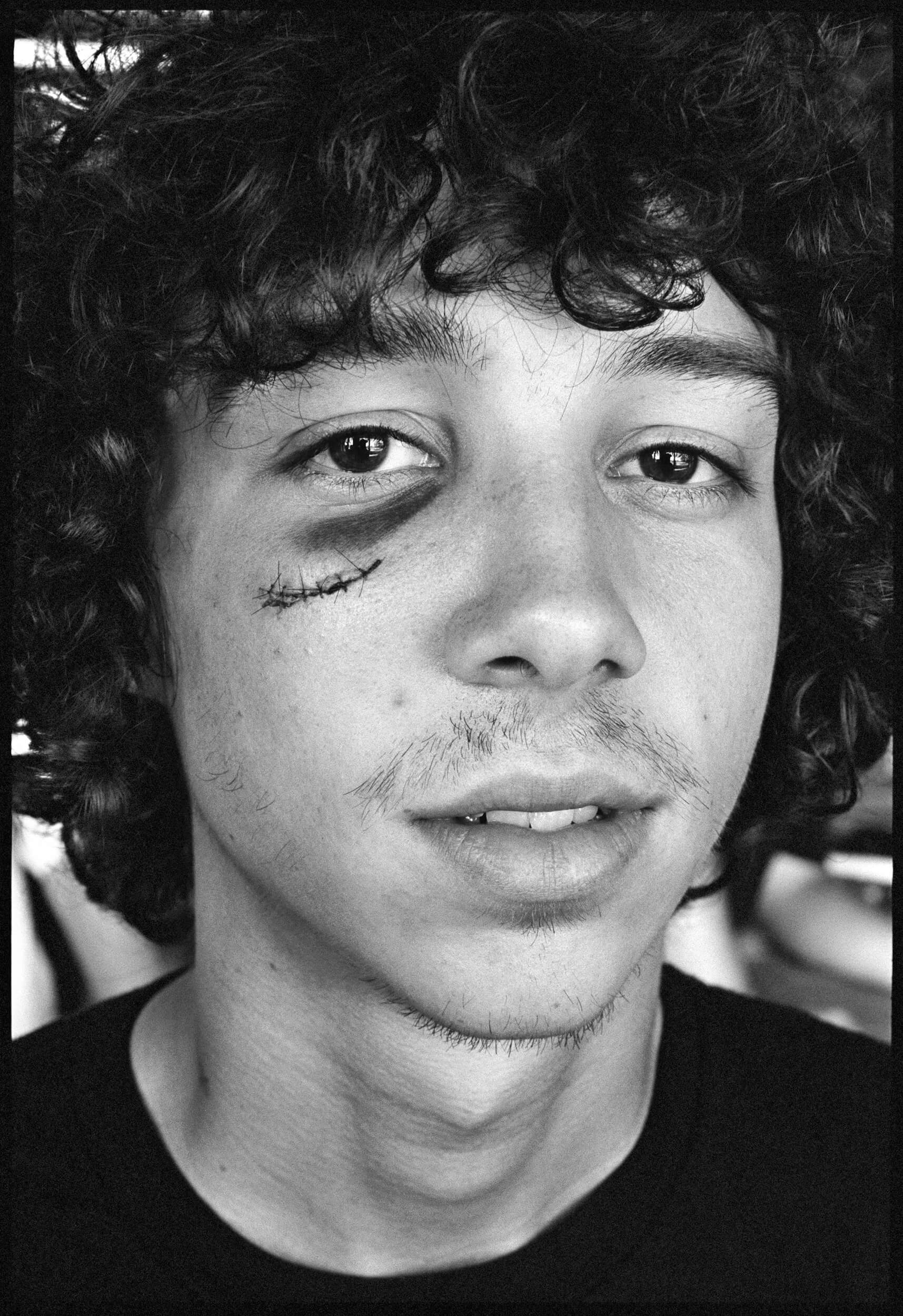

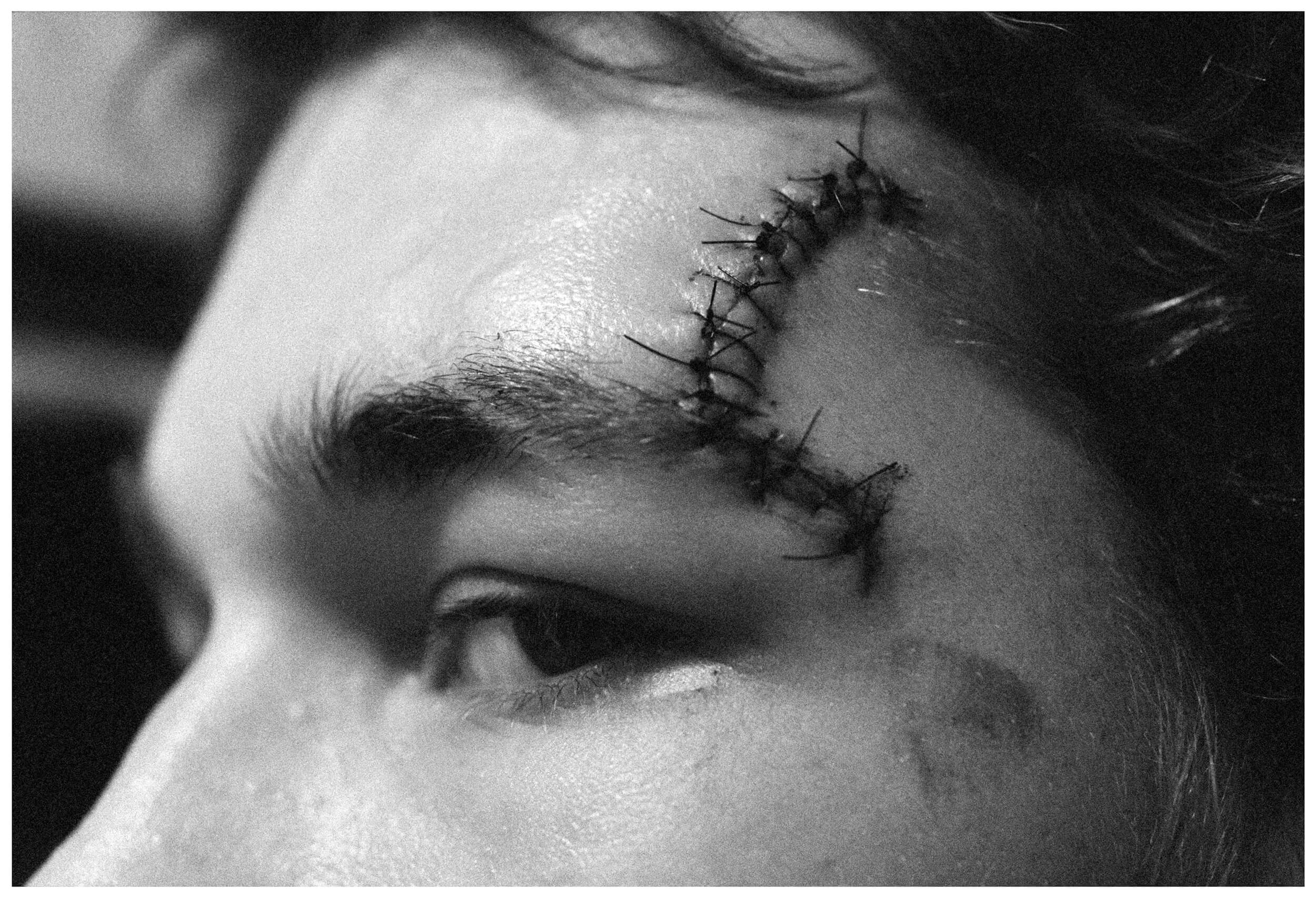

Ed Templeton keeps his followers on their toes. Over the last three decades he has excelled as both a pro skateboarder and contemporary artist. His latest photobook and touring exhibition Wires Crossed was released in 2023, documenting the frenetic DIY skateboarding subculture he was immersed in during the late-nineties and noughties. So far it has shown at Long Beach Museum of Art and Bonnefanten Museum in the Netherlands. The photographs are off-the-cuff, capturing raucous groups on the tour bus; injured skaters with blood dripping out of their knees and noses; and couples cavorting at late-night parties. Wires Crossed follows other books Templeton has published about coming of age, such as Teenage Kissers (2011) and The Golden Age of Neglect (2002).

Templeton now lives in Orange County, in Southern California. He has always painted alongside his skating and photography, creating rich works that capture his surrounding suburban life. His paintings often feature lone characters going about their daily business, walking perfectly preened poodles or carrying loaded grocery bags home. I spoke to the artist as he prepared for a solo show of these paintings at Tim Van Laere Gallery in Antwerp, opening this November.

Everything you [say] is true. When you bring a camera into someone’s face, it’s such an archaic thing at this point that everyone seems to notice it. And everyone is hyper aware. If you look at Wires Crossed, the people I was shooting thought that the photo would just live in this weird archive. Now everyone knows that a photo is directly sharable to the world. People are more self-conscious.

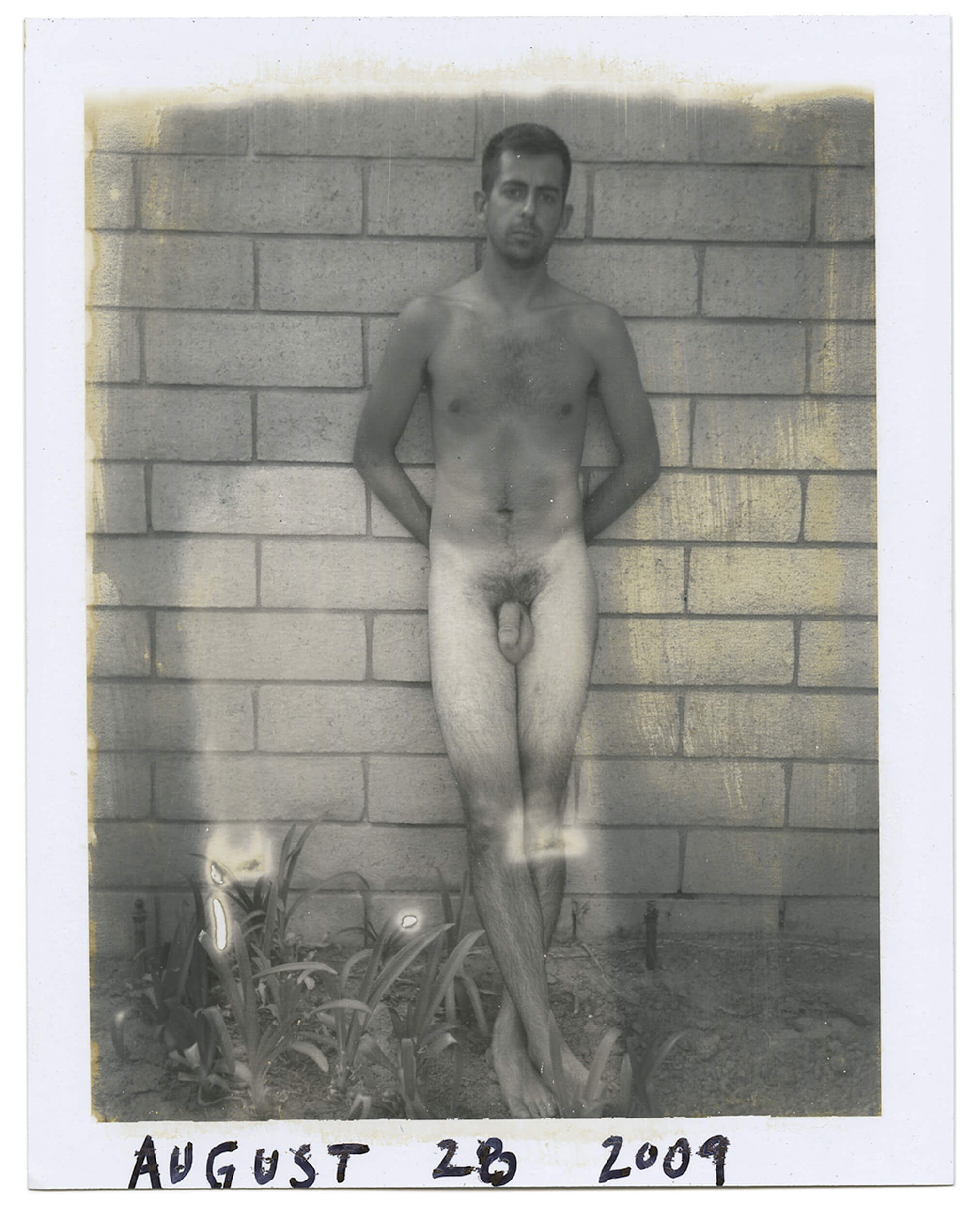

It was daunting! I did a book called Teenage Kissers (2011), which was a bit of an in-joke follow up to Teenage Smokers (1999), and in the years since the book came out, I kept finding photos I didn’t include. With Wires Crossed I really went through every photograph. Inevitably when you look back like that, your tastes have changed, and you find photographs you didn’t consider to be interesting at the time.

Everyone has said it’s ended up being a time capsule. You don’t realise when you’re living in a time capsule of course. But the big cut-off for me is 2012, when cellphones and Instagram came into wide use. The days of just getting into a van for a couple of weeks are kind of rare. A lot of companies now just do one demonstration but not necessarily a big road trip.

At the show, I heard the word “nostalgia” a lot. Everyone who came to the show had grown up reading about these people in magazines. For them, it was interesting to look behind the scenes, seeing these weird photos of people hanging out in vans and hotel rooms, not skateboarding. People in the photographs thanked me for remembering parts of their brain that they forgot. What haunts me is how much I missed. When I was organising the book into themes, I kept remembering things I hadn’t captured. I had a little depression about that.

It’s an air gun! But a lot of people at the show thought that too. I had to do a tour at one of the museums, and the first question was, “Why are you guys carrying a gun on a skate tour?” I was like, “Oh my god that’s totally a plastic BB gun”. But I realised I didn’t say that in the exhibition text. So people are like, are these guys thugs?

It’s funny that you mention that. If it wasn’t for Lesley A. Martin [formerly Creative Director at Aperture], I might have rambunctiously put the book out without thinking about the context. Some of the stuff looks very much to be from the world of toxic masculinity. As a kid you’re just doing stuff, and there is an innocence to it, but society has evolved. It was important to add interviews with the protagonists about how they look back on the work: Elissa Steamer, for example, who was the first female pro skater on our team; my wife, Deana, who was on tour. They both talk about what it was like and how they feel about it now. Someone on the team, after I shot this, came out as gay. So it was interesting to hear how he, as a closeted skater, felt at the time. It placed such an important context on the work.

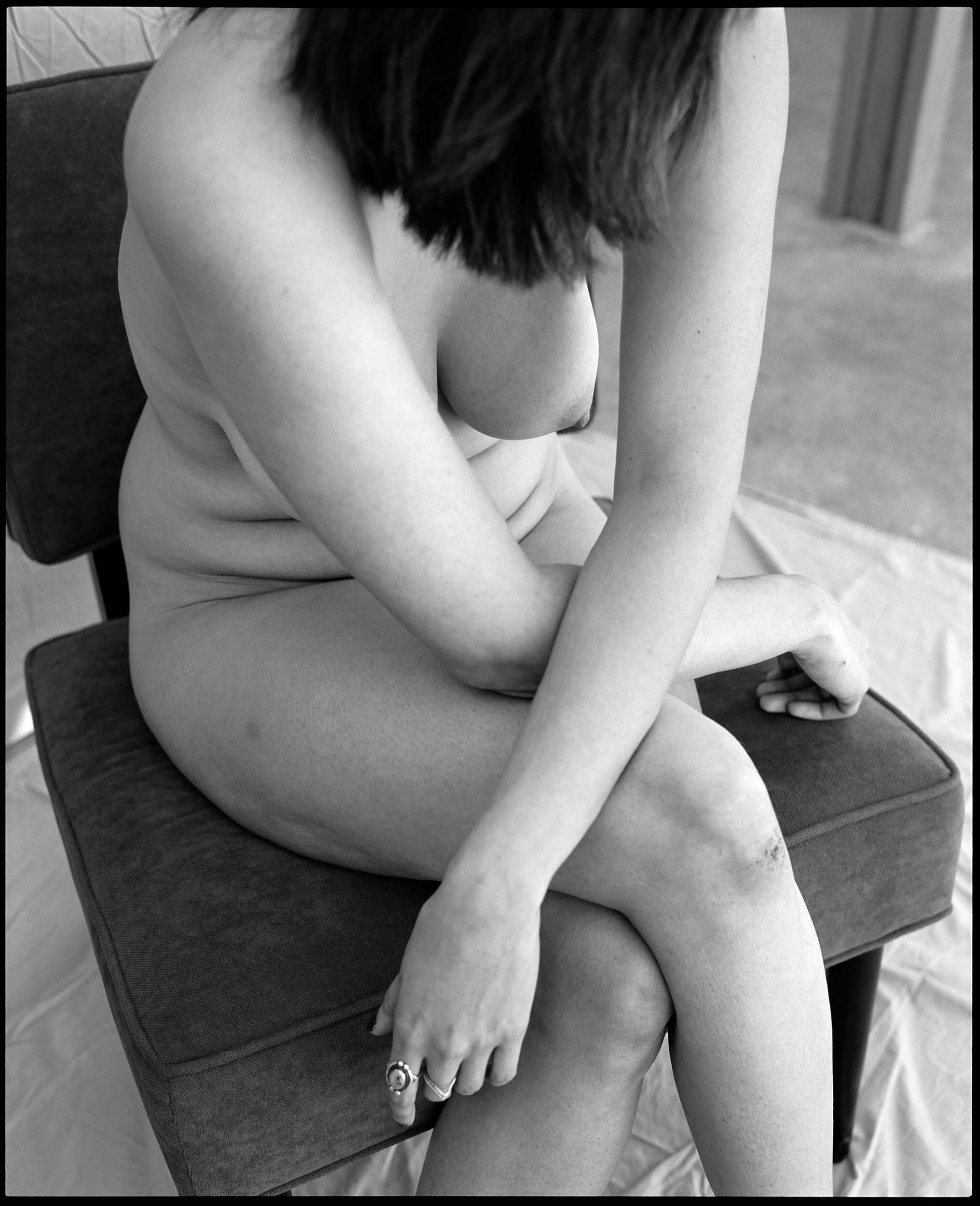

A lot of my early shows involved a gallery coming to me and saying, “Here is a space, come and do what you want”. I’d do these giant cluster shows where I’d fill the space with paintings, photographs and drawings. It was a way to immerse visitors into a certain world or culture. I like the idea of smashing the hierarchies between those things and the juxtapositions that come with it. Especially in my work on suburbia lately, there has been a direct correlation. I use my photographs of Orange County as source material for the paintings. I have even shown my iPhone photos before—I take photos whenever I see anything interesting.

The housing here is built in a very specific way where the street is lined with walls on either side. It’s endemic in Huntington Beach especially—these walled corridor streets that hide the houses. A bunch of activity happens in those little narrow spaces between the sidewalk and the wall. My paintings deal with that little strip.

It seems like the work is more accepted outside of the country, and I don’t know why that is. I feel I have had more success in Europe than anywhere else. There is probably a bit of that export feel, documenting the United States with a not-so-semi-critical eye. Maybe people don’t like having the mirror held up to themselves so much in the States…