To be ambitious participants in fashion we must not turn away from the most pressing challenges of our time: to end extractive labour and environmental practices, to avert climate collapse, to see that we are responsible for and can be part of building a caring world. This challenge requires being critical and clear about what isn’t working in fashion, and also giving our attention and love to everything that is.

Fashion is a collective language, from the way it is made, from soil to skin, to the way we use it to communicate to each other—to belong, to stand out, to remember, to resist—and even to how we work on set—model, photographer, hairdresser, makeup artist, and stylist making images together. So to see what works we have to see an ecosystem. This portfolio, this collection of fashion practitioners, was my attempt to pull back and see–from weavers, to researchers, to ballroom performers, to designers, to activists–radical love blooming all across our industry. When you weave the vertical threads are called the warp, they provide the necessary structure for the weft, the filling, to weave across. The skill and constancy of these five practitioners who hold so much and so many together is part of the warp. I hope it inspires weaving.

– Cameron Russell

Isaac Kariuki

Isaac is a visual artist, who works mainly in the realm of photography, video and performance. He looks at “how marginalised people, especially those in the Global South interact with the internet, new technologies and Western frameworks. I try to be playful and humorous as the research tends to reveal a lot of western biases, contradiction and violence.” Having grown up in Kenya in the mid-2000s, Isaac describes being “barely online” until moving to the UK in 2012: “I went to a very homogenised and centrist university that had really dodgy politics if I truly unpack it. I found actual people I related to online. I think there’s so much to value just in terms of these spaces being so esoteric to your tastes and interests.”

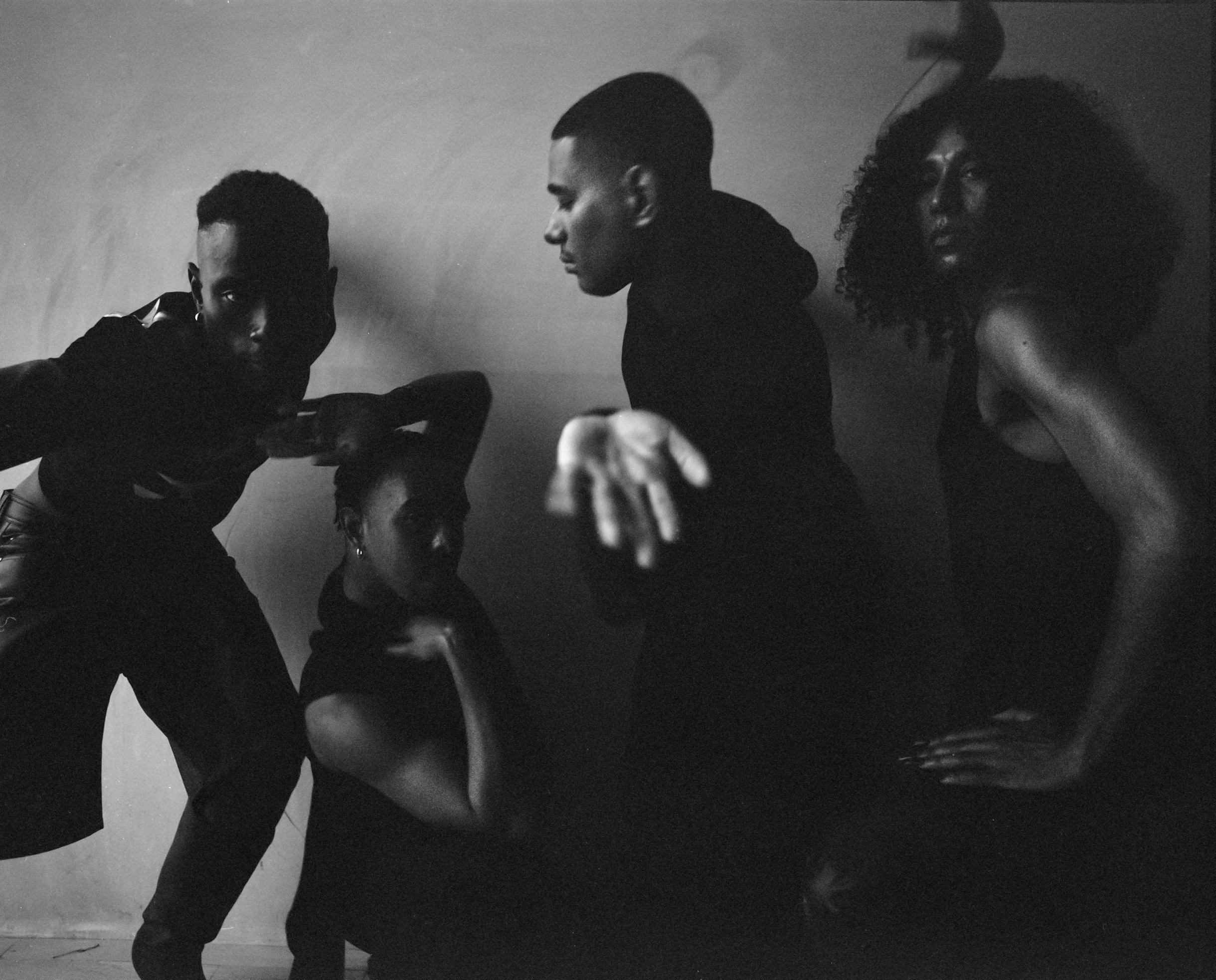

At the start of this year, Isaac co-founded the United House of Watermelon (UHWM) to support and advocate for the Palestinian people. As a symbolic ballroom house with members based around the world, UHWM released an open letter setting out its demands that, amongst other things, the community broke its silence on the ongoing plight of Palestine. If ballroom has been a sort of shelter, if it has allowed participants to experience autonomy and freedom, then it is right to say, “What can we do to extend that shelter?”, and to be in solidarity with anyone whose autonomy and freedom is being denied.

Asian Juicy Couture, an incredible human being, wanted to create a space for people in ballroom who were not only passionate about freeing Palestine but also felt there was a sense of apathy or disunity with what ballroom could do for Palestinians. Ballroom has interacted with Israel on many occasions. There are ballroom houses there, they throw balls, etc., but most specifically, the European scene has had people flying there to give workshops, throw balls and basically legitimise its existence. We collectively don’t feel like that scene can exist. There’s no way an apartheid state can also hold the belief they are liberating queer lives. In the open letter, I wrote that not only can you not slam backs on stolen land, but you cannot advocate for the autonomy of queer and trans people that ballroom helps nurture, while denying autonomy to Palestinians, removing their access to clean water, starving and bombing them.

After moving to the West, I became very aware of hobbies only existing as commodities. You go to work, you go kickboxing or salsa, then you go home. It’s a thing you consume and don’t live. Ballroom is the only exception. You go to a class so that you eventually walk a ball. You join a house and now you have to be a sibling and care for other people. It shapes so much of you and how you navigate the world. I feel really lucky to be transformed by it.

In ballroom, you’re constantly asking to borrow people’s clothes because you know they’re gonna borrow yours. Sometimes it’s not even people in your same house. This one ball, someone I was literally competing with, gave me a piece of jewellery to amp my look. Community means being selfless right? I’ve also been thinking about community when people disappoint you or when you disappoint them and what you all do about that. And the victims too, how would they feel protected and understood. There’s all this Marxist and anarchist literature on rehabilitation, but I’m way more interested in what ballroom comes up with.

I do think to enact change, they eventually have to move offline or do something so world-stopping and radical that essentially destroys the very infrastructure of the internet. The George Floyd protests for instance, were broadcasted online so rapidly, but it took teenagers in Minneapolis breaking COVID restrictions and burning a police precinct. The two work together but the latter is material and consequential.

Ngozi Okaro

Ngozi is an activist and the founder of Custom Collaborative, a New York-based initiative that trains, mentors and equips no and low-income women of colour with the skills to work within the fashion industry. A powerful reorientation in an industry that profits of the exploitation of the labour of women of colour who make, pack, ship, and sell most garments in circulation today and yet rarely make even half of a living wage.

I started Custom Collaborative because I was looking for custom clothing and realised the broader impact that could be achieved if others had access to made-to measure clothing. My journey began with the simple need for clothes that fit well and were thoughtfully made. However, this initial motivation quickly widened in perspective as I recognised how much more impact I could create for other women who wanted clothes that fit, and for women who could (or could learn to) create clothes to meet their needs. My journey has been incredibly enriching and transformative. I’ve had the opportunity to support women from no/low-income and immigrant backgrounds, providing them with the skills and resources needed to thrive in the sustainable fashion industry.

Supporting women who have been pushed to the margins, in community with others who care about the environment and human rights has been very hard and very rewarding. It would be impossible to do the work to a high standard by myself. This work requires both individual and systems change, because Custom Collaborative helps those we work with directly, and advocates for industry-wide changes. Different kinds of support have been critical along the way, from community partners to industry allies, all contributing to a more equitable fashion industry. The journey has been challenging and rewarding.

Our accomplishments show that impactful change is possible both across the entire fashion ecosystem.

It feels incredibly rewarding to see Custom Collaborative Training Institute graduates using the experiences and skills they’ve learned to create careers and community. For example, seeing that several participants will present looks in Remake’s September 2024 NYFW show is a testament to the practical and impactful education they received. The worker-owned cooperative formed by our Training Institute participants stands as a beacon of collective effort and success, with women learning to value and price their work appropriately, sharing their knowledge, and creating a culture of mutual growth and learning.

Sitting onstage at the 2019 LA Film Fashion Festival with Jeanice [Parker], as she showed herself to be a sustainable fashion thought leader was joyous. Witnessing others’ self-actualisation is both a privilege and an expression of personal and organisational investment. It makes me proud to see the concrete results of many peoples’ efforts and determination to do more. The success of our graduates inspires me to continue knowing that every investment we make has the potential to open doors for women’s lives.

Financial support is the most important. Money means that training can happen—both for employers and employees, in areas like zero waste design, low-water dyeing, up to date equipment, worker rights, advocacy for small businesses and workers, etc. Financial investment is critical for making fashion more sustainable. One of the most impactful ways to foster sustainability in fashion is by investing in local communities, particularly those that have been and still are marginalised. This includes providing education and resources to people and creating pathways for them to gain skills and opportunities in the fashion industry. By uplifting underrepresented voices, we ensure that the benefits of sustainable practices are shared equitably leading to sustainable growth and development for all. Committing to fair trade practices is also essential for a sustainable fashion industry. This means ensuring that all workers in the supply chain receive fair wages and and work in safe conditions. By supporting fair trade, Custom Collaborative not only promotes ethical labour practices but also contributes to the overall wellbeing of communities that produce fashion. This approach helps to reduce poverty and promote economic stability, which are fundamental to sustainable development.

Laura Moseley

Laura is a curator, researcher and the founder of Common Threads Press, which publishes histories of craft. Working with researchers, makers, writers and more, the press produces radical zines that seek to amplify craft in radical and collaborative ways, from histories of natural dyeing processes, to looking at traditions of Hawaiian quilting alongside colonialism and the climate crisis.

Though Laura describes Common Threads Press as “a small operation that I run out of my flat” their publications are stocked in independent bookshops and art institutions in the United Kingdom and internationally, while they also host regular events in collaboration and in conversation with makers.

Common Threads Press is a project dedicated to celebrating all forms of craft and making through publishing and events, but with a particular focus on how it relates to social histories, activism and community. I started it in 2019 because I was so inspired by the by the history of independent grassroots publishing, particularly zine making, that has highlighted people and cultures that we don’t typically see in mainstream publishing. I wanted to create a space for voices that explore the relevance, importance and role that craft continues to play in our cultural and creative experiences.

Amplifying those who need to be heard the most is the very least that those with privilege or a platform need to be doing right now. We need to fundraise, campaign and rally behind them to help ensure that everyone has freedom and safety. Common Threads Press is always going to be limited in how much it can do that, as we’re a two person operation, but hopefully we can show people that there are other forms of activism and consciousness-raising available to them. It also gives many of our authors a platform to discuss their own experiences and research, for example, Gill Crawshaw writes about the protest textiles made by disability activists, Isabella Rosner writes about how those in incarcerated states have found a way to embroider, and Jess Bailey discusses the importance of quilt-making for activists from the early twentieth century to now. It’s important that we publish these histories so we can be inspired by the creative ways in which people have historically resisted and protested.

Cynthia Alberto

In 2006, Cynthia had a “lightbulb moment, I am going to open a weaving studio in Brooklyn.” Though she had studied textile surface design at the Fashion Institute of Technology and had been teaching small weaving workshops at the Children’s Museum of Manhattan, there were different challenges that came with a studio: “I had no idea how to start a business, or what looms to buy.” Over time, Weaving Hand grew as a studio, incorporating a healing arts programme, and became a pillar of the community.

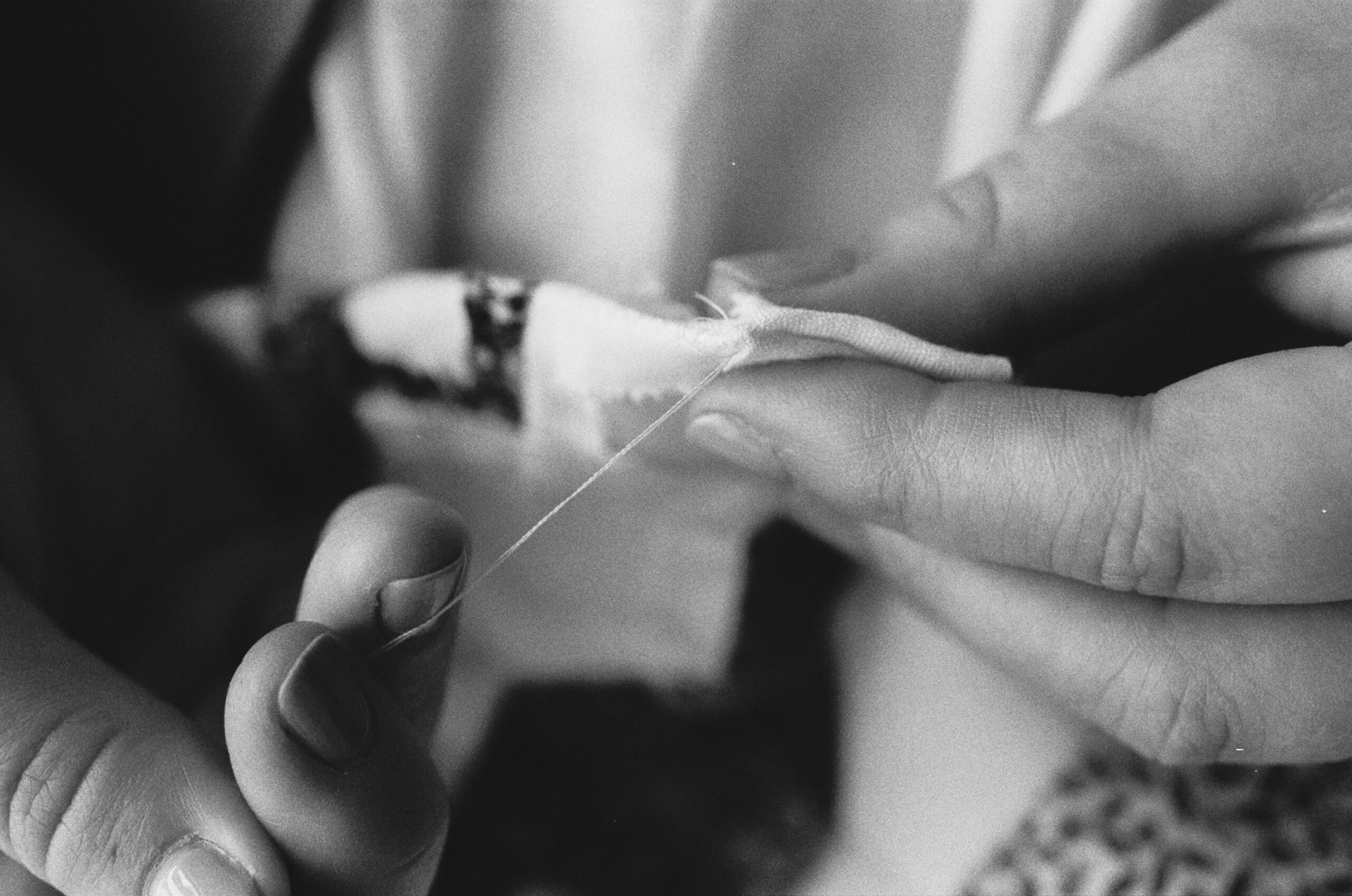

Cynthia started “Weaving Together” in 2016, a community event first held in Brooklyn. “My fabricator and I designed the very first table-top looms, a communal loom similar to a table where you can weave and face each other, have a conversation while weaving.” Since then, Weaving Together events have been held at museums, public parks, schools, hotels, galleries, and so on. This summer saw the return of Weaving Together, with interactive weaving artworks installed across Brooklyn as part of the city’s Summer Streets project. This followed Cynthia’s diagnosis with stage IV lung cancer in May 2023, following which she closed the Weaving Hand studio after seventeen years. Reflecting on this year’s event, Cynthia says, “I am so thankful I get to do this again, and to be out and about enjoying the city, people and weaving….When I started the healing arts programme, I would always say weaving to heal to the students. Where I am now in my life journey, I am weaving to heal every day. Weaving Hand does not have a physical space at the moment, but I believe it lives [on] in people’s spirit. It was a very special place to weave, have a cup of tea, talk and dream. And perhaps one day it will have a physical space again…”

Community is everything that we need to evolve as good people in this world. We have to teach our future generations about the importance of being part of a community, to take care of one another, to learn empathy, to grow together….I am a first generation immigrant from the Philippines. I first learned about community when we arrived in Jersey City in 1977; the Filipino community welcomed us and [made] sure the kids had coats, boots, food to eat for the harsh New Jersey winter. It taught me about community and the power of community. Through community, you can collaborate with other communities to help, learn, uplift and celebrate together. I believe community and collaboration go hand in hand together.

All over the world, there are so many weaving traditions, and we are now finally recognising weaving as a very special art form….In the Philippines, when I was young, nobody wanted to buy traditional textiles; they were all made for tourists, we wanted American-made clothes. But that perspective and understanding has changed. People are now proud of the traditional textiles, embracing the culture and uplifting indigenous communities. I see it as claiming their identity and history. Weaving is a world language: different countries have their weaving traditions and identity. Teaching younger and future generations about weaving histories connects them to the earth and grounds them to make sure that they don’t lose the understanding that their hand is magical, and it can make anything—“Hand Made”.

Especially where I am now in my health, I weave to relax, to let go, to be peaceful. To be thankful! Weaving is also a very happy, joyful celebration for me, gathering everyone, seeing everyone smile, holding a piece of yarn: we are all weaving and healing one another. When people weave around me, they become part of the big tapestry we call human connection, and everyone is repairing or enhancing our human tapestry. I am forever grateful to Weaving Hand, it has given me so much and it will always be in my heart. We need more spaces like Weaving Hand to keep us grounded and, of course, to learn how to weave. But most importantly, the power of human connection cannot be lost.

Benjamin A. Huseby

Benjamin started the Berlin-based brand GmbH in 2016 with Serhat Isik. Taking its name from the German acronym for a limited company, GmbH is a design collective with multiple designers. “Our name was deliberately anonymous to shift the focus away from us as individuals, onto the collaborative work we do—both as Serhat and I, but also with the other people and brands we collaborate with,” Benjamin explains. The pair met in 2015 through Berlin’s rave scene—Serhat was working in menswear, while Benjamin’s background was in fashion photography. Their work together draws inspiration from Berlin’s renowned underground scene: paying homage to queer nightlife culture and multiculturalism through an inclusive approach to design and displaying their collections. That inclusivity reflects the diverse backgrounds of GmbH’s members—Benjamin is of Norwegian and Pakistani heritage, while Serhat is Turkish and German: and as such, stories of migration form another pillar of the collective’s approach. These values, and often more political statements, have been woven into the fabric of their menswear and womenswear collections from the beginning.

For FW24, GmbH presented a collection that drew inspiration from the Palestinian keffiyeh, worn as scarves and reworked into tailoring. Using keffiyehs made by SEP (Social Enterprise Project)—which are embroidered by hand at the Jerash refugee camp, or Gaza camp, in Jordan—GmbH then crafted the jackets at their Berlin atelier for the collection. Titled “United Nations”, the collection also drew on the UN’s logo as a printed motif on hoodies, leaning into the idea of tolerance and collectivity beyond nation borders.

Benjamin and Serhat opened their FW24 show in Paris by “[calling] for a ceasefire now, a release of all hostages, a free Palestine and an end to the occupation. All demands we think should be uncontroversial.” That GmbH have openly used their platform as designers at Fashion Week was a recognised as a powerful action to make. In July, Benjamin and Serhat returned to show their SS25 collection in Berlin (on account of this summer’s Olympic Games in Paris). Titled “Resistance Through Rituals”—a reference to the 1976 book on subcultures of the same name, edited by the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall—the collection paid homage, amongst other things, to the student protests that have occurred on campuses and to marches that have taken place across towns and cities worldwide, week in and out. In their show notes, GmbH asked, “What is resistance? Resistance is believing in a better world for everyone and fighting for it.

It meant I had experience as an image maker, which I think is valuable for a fashion brand. As without imagery it is just clothes without any context.

As people we have always wanted to highlight topics important to use where we feel we can be a positive force, using GmbH as a platform. It is essentially about supporting and amplifying voices already out there, together with our own.

I think it’s important for building community and connecting with people in a way that they may feel less isolated. That’s very important for any political movement.