Derived from the Moorish Arabic wādī al-ḥajārah (وادي الحجارة) meaning Valley of Stones, self-taught artist Jose Dávila was born in the municipality of Guadaljara, Mexico. By then a bustling metropolis, the chaos and instability of the precarious urban environment in which Dávila recalls growing up in the 1970s and 1980s—and where he still lives and works today—is juxtaposed with the quiet but profound presence of Guadalajara’s rich, natural landscape.

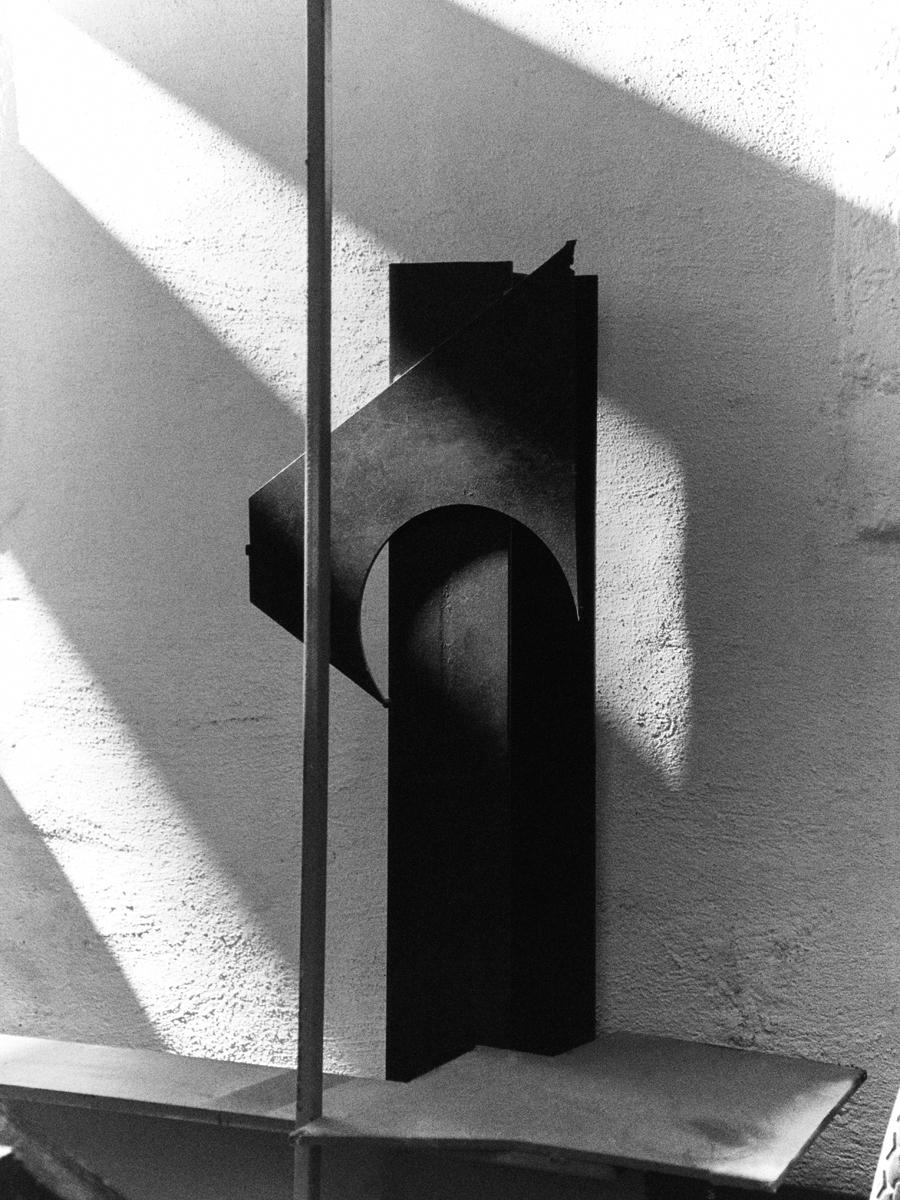

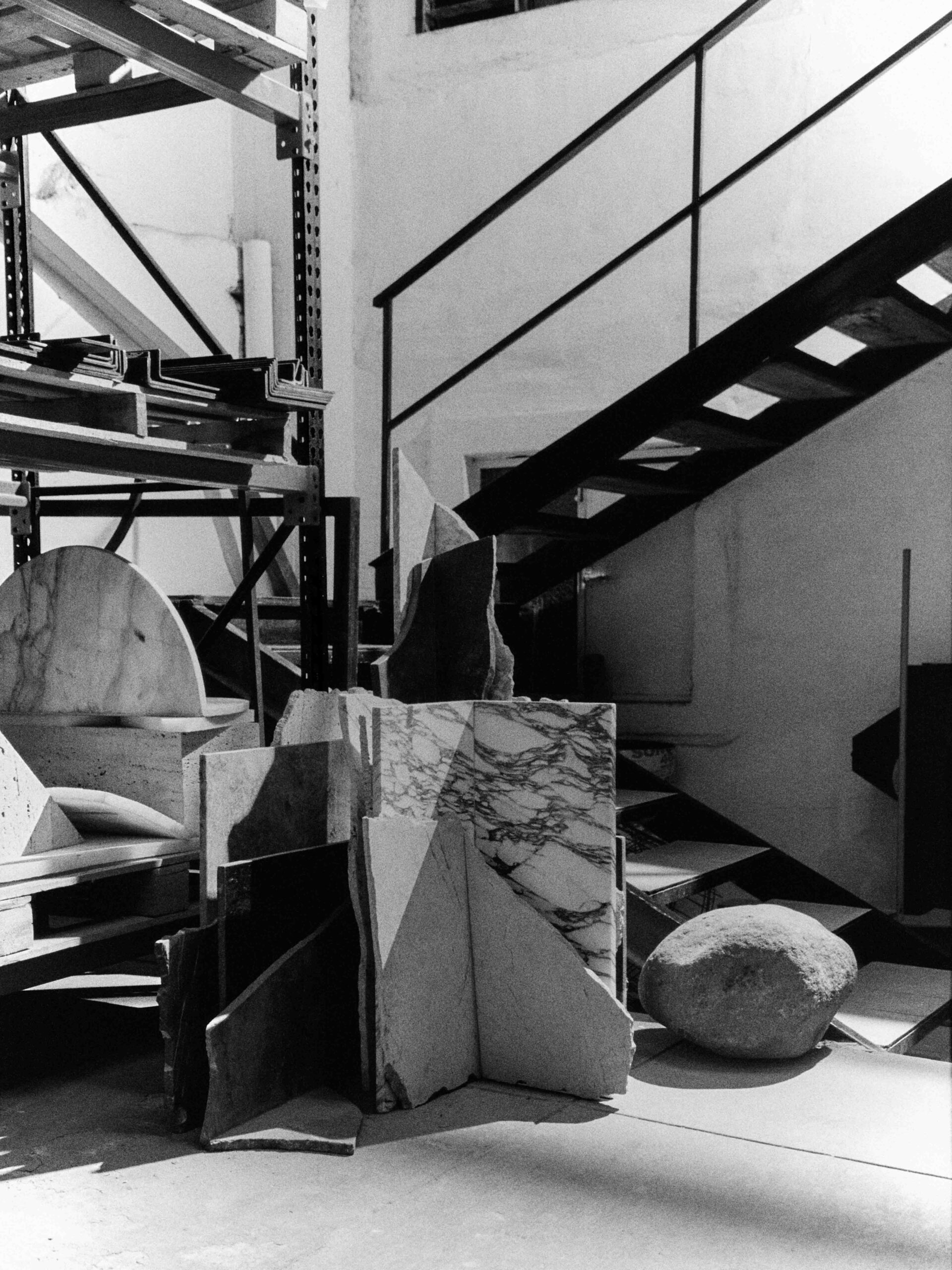

Formally trained in Architecture at the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudio Superiores de Occidente (ITESO), Dávila explores the act of creation together with a skilled team of collaborators at a trio of workshops that conceptually compartmentalise his painting, photography and sculptural installation practices. Embodying the balance, tension and “unpredictable, almost theatrical moments” that are commonplace within both creation myths and urban and natural environments, Dávila’s sculptural installations in particular explore the interplay of forces enacted by found materials—from the standardised convention of industrial materials such as concrete, glass and steel to the raw, ancient qualities of historic natural depositaries such as Pietra dei Medici marble and volcanic rock.

Commissioned for display in diverse locations around the world, as well as found in the public and private collections of international institutions such as Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) in Mexico City, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, Dávila’s site-specific works often require assembly in the context of prestigious urban landmarks and remote rural geographies. Choreographing ‘romantic’ installation and deinstallation processes, the realisation of these pieces is made possible with thanks to their detailed and meticulous logistical planning.

While performing their chosen ‘actions’ and ‘collective positions,’ Dávila’s works serve to provoke awareness within their spectators, engaging the reptilian part of the brain, alerting the senses and forcing reflection on one’s relationship to “possible collapse”—an act which, as Dávila suggests in this interview, is one of both creativity and mutual participation.

Growing up in Guadalajara during the 1970s and 1980s meant being surrounded by contradictions. The city was rapidly expanding, but it retained a certain provincial essence. Guadalajara is a mix of modernity and tradition colliding in real time. For me, it was an education in observing how structures, both physical and social, form and dissolve. The chaos of the city became a backdrop that sharpened my sense of precarity and balance, themes that would later manifest in my work. I was always aware of the tension between permanence and impermanence, a reflection of Guadalajara’s evolving identity.

Yes, absolutely. Living in Guadalajara, a city always balancing its historical roots and its contemporary aspirations, gave me an acute awareness of fragility, as our heritage is being constantly demolished. The precarity in my work often mirrors the precariousness of life. This environment taught me to see beauty in instability and to explore the tension between what endures and what inevitably shifts.

I often think of it as a place for dialogue. In that sense, it is an event of communication between elements in the work and also with the public. Life in Guadalajara unfolds as a series of unpredictable, almost theatrical moments. Vendors setting up precarious stalls on uneven sidewalks or watching a stack of crates carefully balanced on a rickety bicycle wobble through traffic. These moments encapsulate a kind of choreography of survival. They’ve deeply inspired my work, particularly my interest in balancing acts and the interplay between forces that seem at odds yet find a way to coexist.

The landscape surrounding Guadalajara has always been a quiet but profound presence in my life. The Canyon just on the edge of the city and the vast horizons create a stark contrast to the density of the urban environment. I lived for some years in a tall building [from which] I could see the sunset everyday and the mountains where the city ended and nature started. It’s this juxtaposition that informs much of my work. The raw, ancient qualities of the natural world often find their way into my practice, both materially and conceptually, as I explore the relationship between the built environment and the ancient materials of nature, like stone.

I aim to evoke a sense of awareness—to make people conscious of their own balance and positioning within space. The tension in my work isn’t meant to be unsettling for the sake of discomfort; rather, it’s a way to make viewers pause and reflect on the fragility and resilience inherent in life, in all systems, as a device to unlock awareness. I want the audience to experience a moment of equilibrium, however fleeting, and to question their own relationship with imagining a possible collapse, which is a form of creativity. The work should trigger imagination.

Each material carries its own personality. Concrete feels grounded and stoic, glass is fragile yet defiant…, steel exudes strength but can also appear vulnerable when bent or under stress. Stones, I say, are man’s best friend. Driftwood, on the other hand, carries the memory of its journey, its weathered surface telling stories of time and transformation. I try to understand the stories materials tell. Like people, they all have a history and a personality.

Plasticine taught me the fundamentals of form and play. I spent lots of time in a hospital bed as a child, playing with plasticine. It’s a special memory, but as I matured, I became drawn to the permanence and history embedded in found objects and raw construction materials. These materials, found in architecture construction under process, carry a sense of time and place that traditional sculpting mediums often lack. They also offer an inherent structure and resistance that challenges me to find ways to integrate them into precarious compositions.

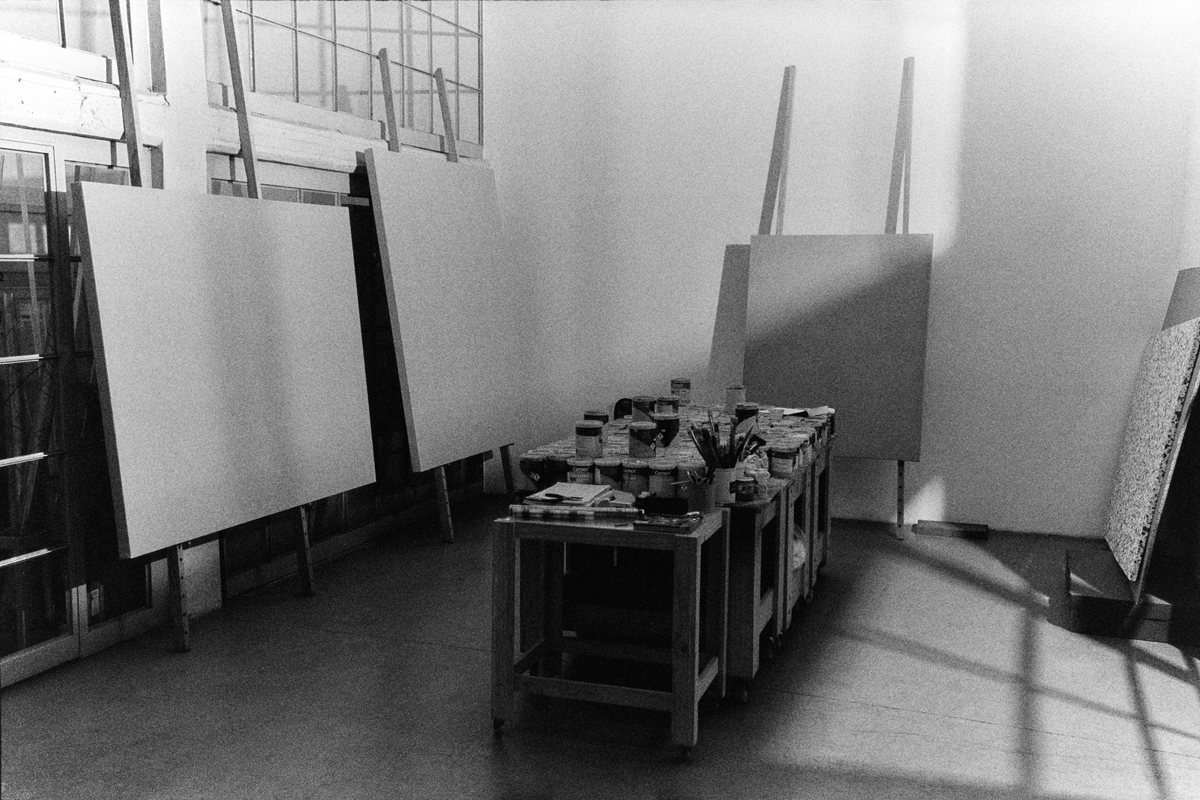

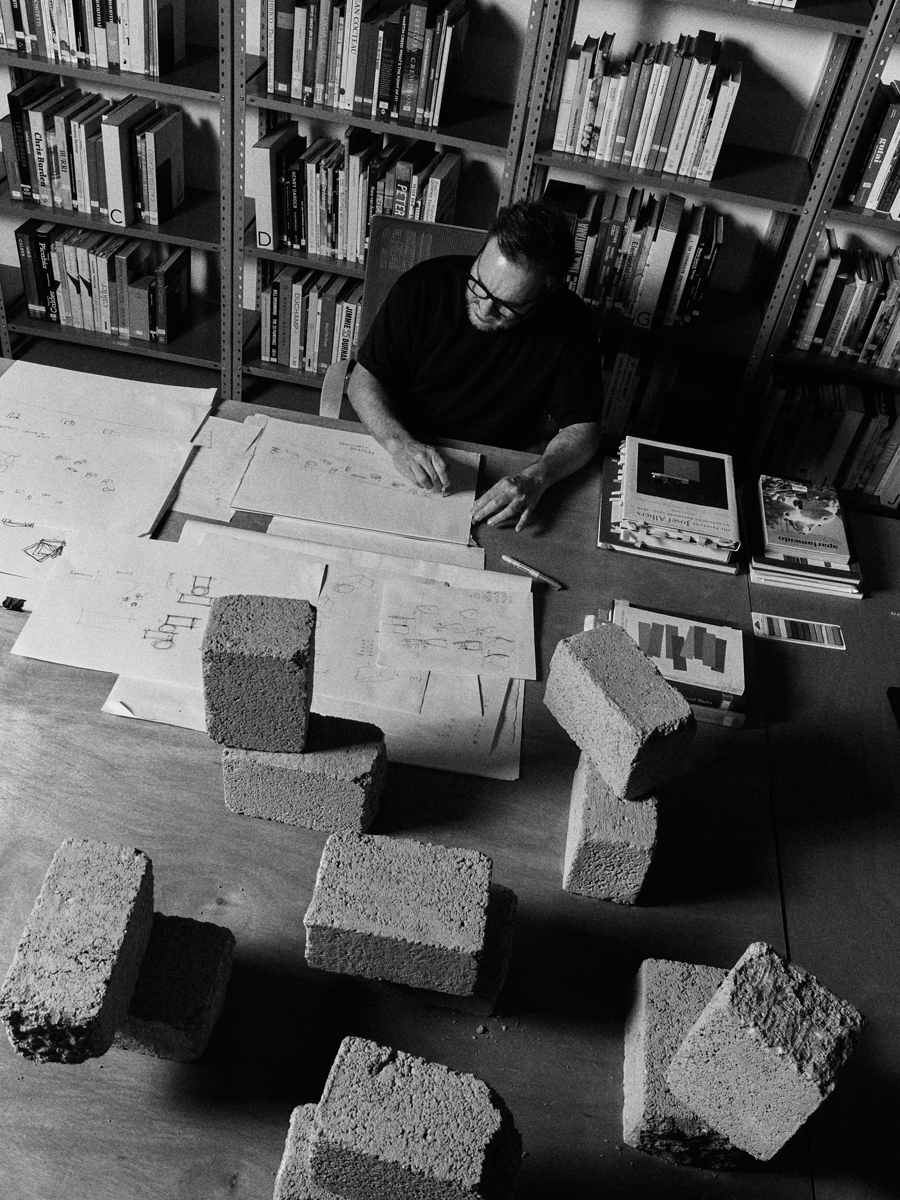

My studio operates like a workshop and an architecture office of some kind, a space of experimentation and problem-solving. It’s divided into areas for research, fabrication and assembly. I divide my painting and graphic work studio (2D) from my sculpture studio (3D) and I have a team of skilled collaborators who assist in everything from technical drawings to material handling. I have three studios within metres of each other in the same street, where very different activities happen in each and I try to adapt my mindset to the nature of each studio. While much of the preparation happens in the studio, from assembly to adjustments I often improvise on-site, as the context of the location becomes an integral part of the work as well.

Public installations demand sensitivity to their environment, but more specifically, to the people they are going to interact with. That’s my main concern always. Each location has its own narrative, obviously. My goal is to try to see the place with fresh eyes. Even if you were to walk by everyday, the work should adapt, and at the same time, change the place. If it’s not going to make it a better place, then it shouldn’t be installed. The work should be a device to assist in the process of re-discovery. In the end, it’s just a form of dialogue.

In Peccia, the rugged mountains demanded a dialogue with their monumental presence, while in Palma, the work needed to engage with the lightness and rhythm of the maritime plaza. Regardless of the site, my focus is always on creating a sense of harmony that resonates with the specificities of the location. The universal elements in my approach are abstract, like the exploration of balance, tension and symbolic meaning.

Natural materials like marble and volcanic rock have a timeless essence, they were here before us and they will be here after us. I source these materials through collaborations with quarries and local artisans, ensuring that their history and provenance become part of the work’s narrative. I find it fascinating to work in a contemporary way with materials that have been used for thousands of years.

Transporting my works requires meticulous planning. We spend a great deal of time at the studio going into detailed planning and making diagrams for future installation and de-installation; it’s a collaboration with specialised teams. It’s the ‘invisible’ part of the work that takes an enormous amount of time. Each piece is carefully disassembled and packed to ensure its safety during transit. For remote locations, the logistics often involve adapting to challenging terrain, hiring cranes and planning how much load an open bed truck can carry. It’s a crazy amount of logistics that you don’t see in the work, but it’s always there. For me personally, it becomes part of the work’s journey and narrative.

I do view my process with a certain romanticism, as it’s a collective act of creation that requires trust and coordination. This romanticism turns the act of making into a shared ritual with the team at the studio that we have created. For me, it’s essential to find beauty in the process, as it informs the final piece with a sense of intention and care. I enjoy the process very much as I like working in real time with 1:1 scale materials. And just as with sketching ‘live,’ suddenly beautiful moments of human coordination can happen as a by-product of the simple act of moving things around and on top of each other.

Many of my temporary works are dismantled, and their materials are often repurposed or recycled. I love this part because I like to work with materials that are not at all or minimally modified. They are an artwork as long as they are performing a certain ‘action’ and ‘collective position,’ but if you dismantle the work, you could use the materials again, just as they are. Whether a piece of glass or a stone, they return to being ‘just’ materials again. This process reflects my fascination with the cyclical nature of creation and the symbolic quality of things, ensuring that even after their ‘participation’ in an artwork, the materials could continue to have a life and purpose beyond it.