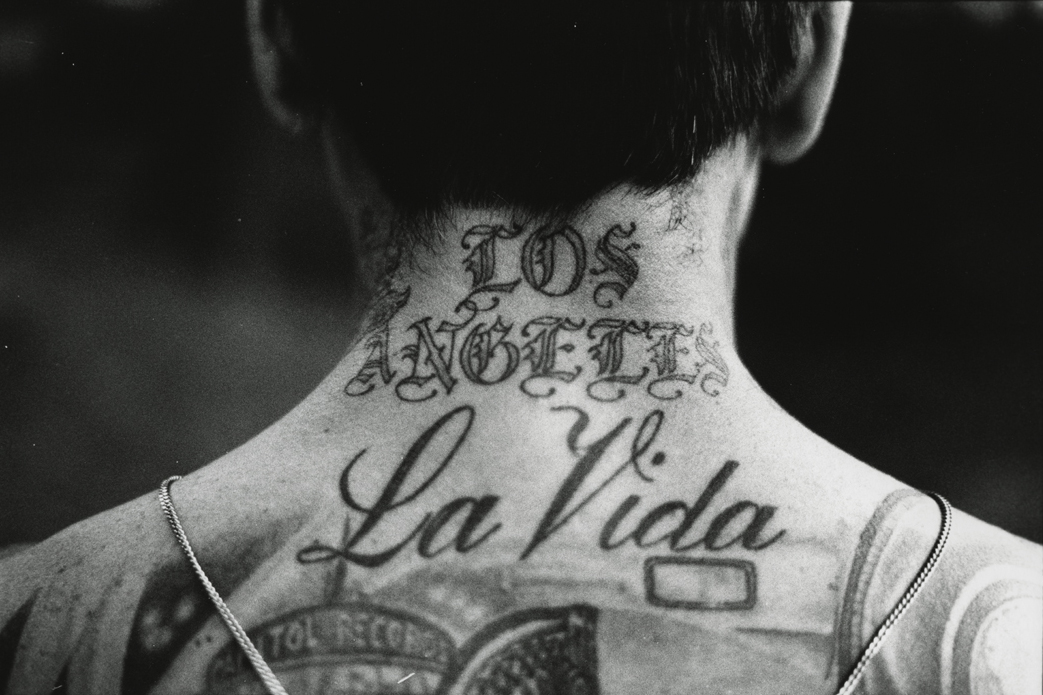

Cholo style was born from struggle. The Pendleton flannel shirt buttoned up top, oversized khaki pants meticulously creased, dark shades paired with classic Nike Cortez sneakers and long white socks. Or the chola look. The definitive flannel, accompanied by baggy jeans, long hair and spikey bangs, and heavy lip and eye liner. Mix in a lowrider cruising the boulevard with a bumping Chicano hip-hop soundtrack and one can imagine the essence of cholo cool. And yet, cholo has long been more than fashion archetype. It is a Mexican-American identity and way of life that grew from a gritty history of discrimination and exclusion. To borrow from Tupac Shakur, cholo style is like “the rose that grew from a crack in the concrete [1].”

Cholo is a kaleidoscope of the Mexican-American experience. Its genealogy dates back to the Spanish Conquest in the fifteenth century. The Nahuatl word xolo, meaning ‘dog,’ was hurled as an insult against Indigenous and mixed-race mestizos. It was meant to dehumanise them and enforce a racial order, with White-skinned Spaniards at the top. Fast-forward to the twentieth century, when young Mexican-Americans reclaimed cholo to embody a spirit of ethnic pride and dignidad. Their cholo style grew from life in barrios plagued by poverty, hostility from law enforcement, and neglect by schools and society at large. It was also organic to gang and pinto, meaning ‘prison,’ culture, often criminal and violent.

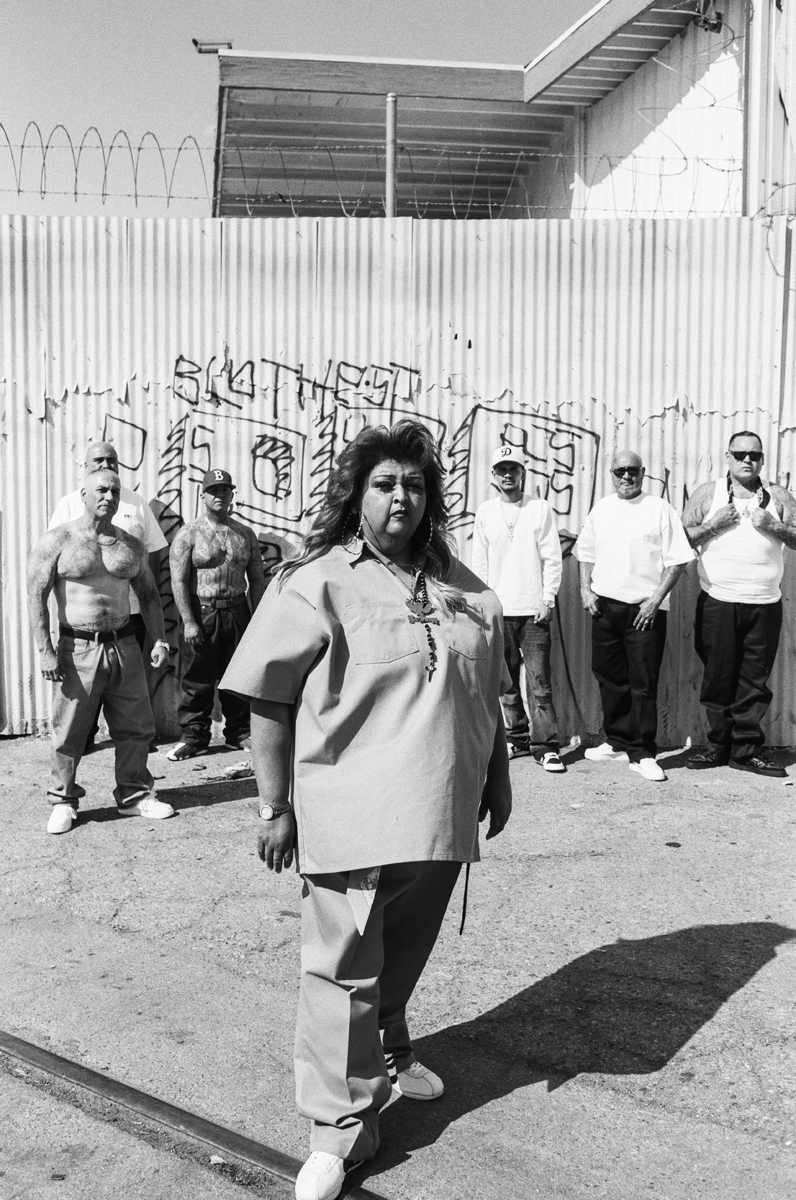

There is no singular image of who or what a cholo is. Their history is one of anguish and joy, survival and self-destruction, and an unbridled refusal to conform. Cholos lay bare the way in which young folk of Mexican descent unabashedly clapped back at power.

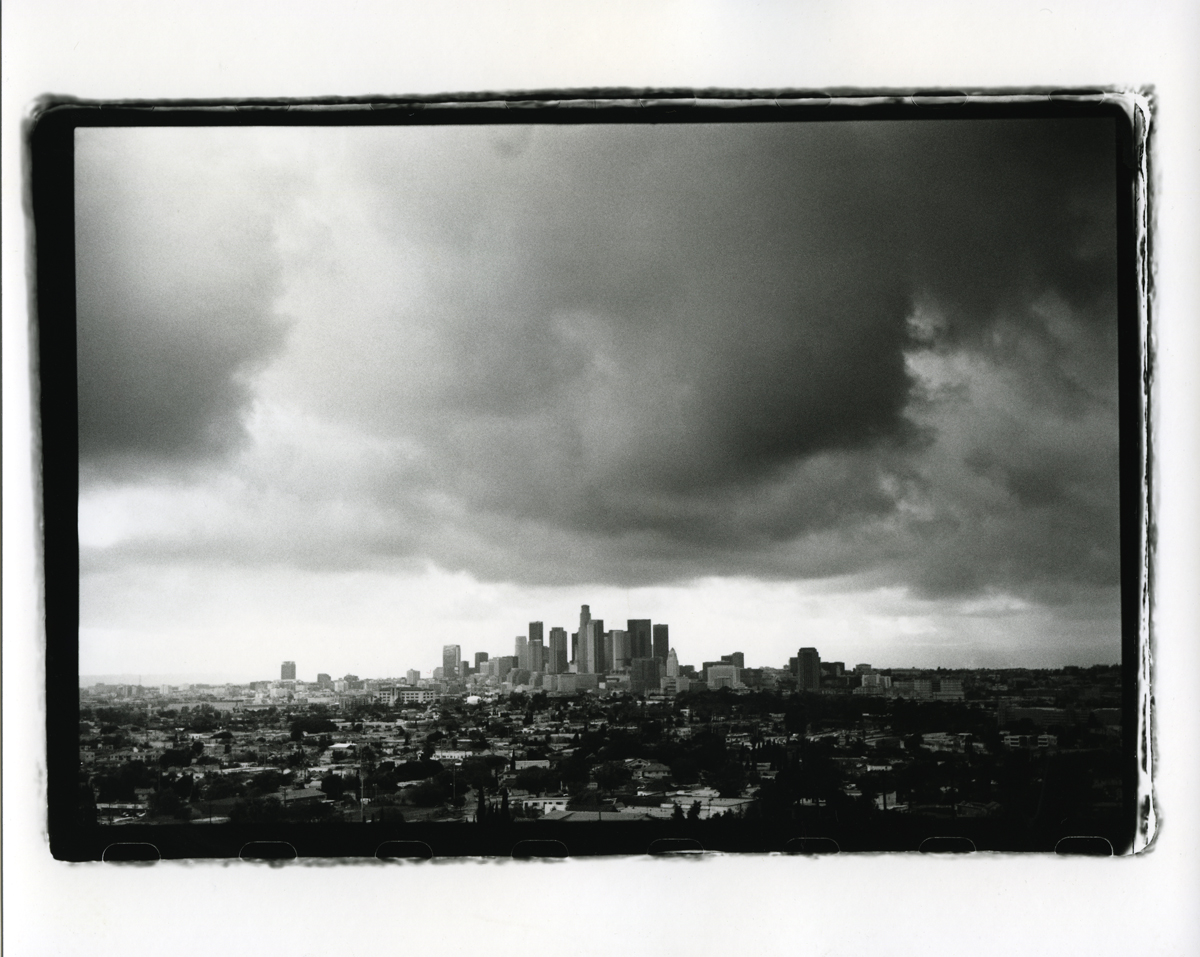

Few would argue that Los Angeles is not the cradle of cholo innovation. The City of Angels is home to more than 1,200,000 people of Mexican descent. More than triple that number reside in the greater metropolitan area. LA is no longer part of Mexico, but it remains Mexicano. To catch a glimpse of cholo life in LA, one need only gaze at the hypnotic photography of Estevan Oriol or the world-renowned tattoo art of Mark Machado, aka Mister Cartoon, both of whom comedian George Lopez called “Cholo Da Vinci’s [2].” Read the gripping tales of gang life in East LA by Luis J. Rodriguez or Randol Contreras [3], nod your head to the beats and rhymes of Cypress Hill, or simply listen to cholo voices, past and present. Their history is entrenched in an LA megalopolis layered with sediment and bruises from centuries of Spanish and American empires. Cholo roots run deep in this crossroads.

Before the cholos, there were the pachucos. During World War II, their signature style included flashy zoot suits and an aura of defiance. They wore baggy pants, known as ‘drapes,’ that ballooned at the thigh and tapered closely at the ankle. Oversized coats, pancake-brimmed hats, gold watch chains, and double-soled Stacy Adams shoes amplified the look. My great uncle Antonio roamed the streets of East LA in his zoot suit in the early 1940s as part of the Club 21 gang. He remarked that, without broad shoulders or an imposing attitude, “you’d look like a thumbtack” with the wide-brimmed hat on top of a scrawny frame[4]. Young Mexican-American women, or ‘slick chicks,’ fashioned their own zoot style. They wore short skirts, long socks, and high pompadours with heavy makeup.

Pachucos were first-generation, United States-born children of Mexican immigrants who fled the Mexican Revolution. Their parents settled in barrios, like East LA, during the 1910s and 1920s in search of the sueño Americano. They weren’t Mexicano in the same way as their immigrant parents. Neither were they fully accepted as American. Out of circumstance, they found comunidad in gangs like the legendary White Fence or Maravilla sets. Their zoot style was inspired by Black American jazz and big band scenes. This Mexican-American generation blended their Mexican roots with their American upbringing. To borrow from poet Bobby Byrd, pachuco culture was “puro border,” filled with the “cross-contamination of our language and culture. It is like a biological weapon, an organism that grows into the shape of who we are and where we live. It feeds on words and sentences spoken in the streets and alleys of our cities and towns and pueblos on both sides of the line… [5]”

Like the cholo style that followed, the zoot was a cultural badge of honour. An especially bold statement during World War II, its flamboyant measurements and colours clashed with the all-white or olive-green, tight-fitting uniforms of sailors and soldiers. It was a contrasting vision of American identity. As such, pachucos were viewed as unpatriotic and un-American. They were treated as criminals, even accused of doing Hitler’s work to undermine the fight against fascism. As journalist Gustavo Arellano observed, “The zoot suit era is when White America learned to stereotype young Latinos as threats[6].”

Pachuco bodies were canvases for style. They were an affront to ‘Juan’ Crow segregation that barred Mexican-Americans from movie theatres, restaurants, and public swimming pools, a West Coast derivative of the Jim Crow that preserved racial apartheid in the Deep South. They transgressed racial boundaries by frequenting Black jazz joints and mixed-race dancehalls. Male pachucos were accused of being too feminine for the constant attention they paid to their clothes and hairstyles. Meanwhile, female pachucas defied the expectation that girls shouldn’t be running the streets with boys. Without apology, they projected an American identity that was not fundamentally White.

Unsurprisingly, pachucos drew the ire of LA society. Racial tensions escalated in the early war years. Then in August 1942, 22-year-old Jose Diaz was murdered in a gang fight near a popular swimming hole called Sleepy Lagoon. More than 600 zoot suiters were rounded up by police; 22 were arrested and their mass trial garnered international attention. Months of sensational press painted pachucos as subversive to the war effort and a black eye for LA. Fights between zoot suiters and servicemen spread across the city. One fight was an excuse for the next. Los Angeles was a powder keg.

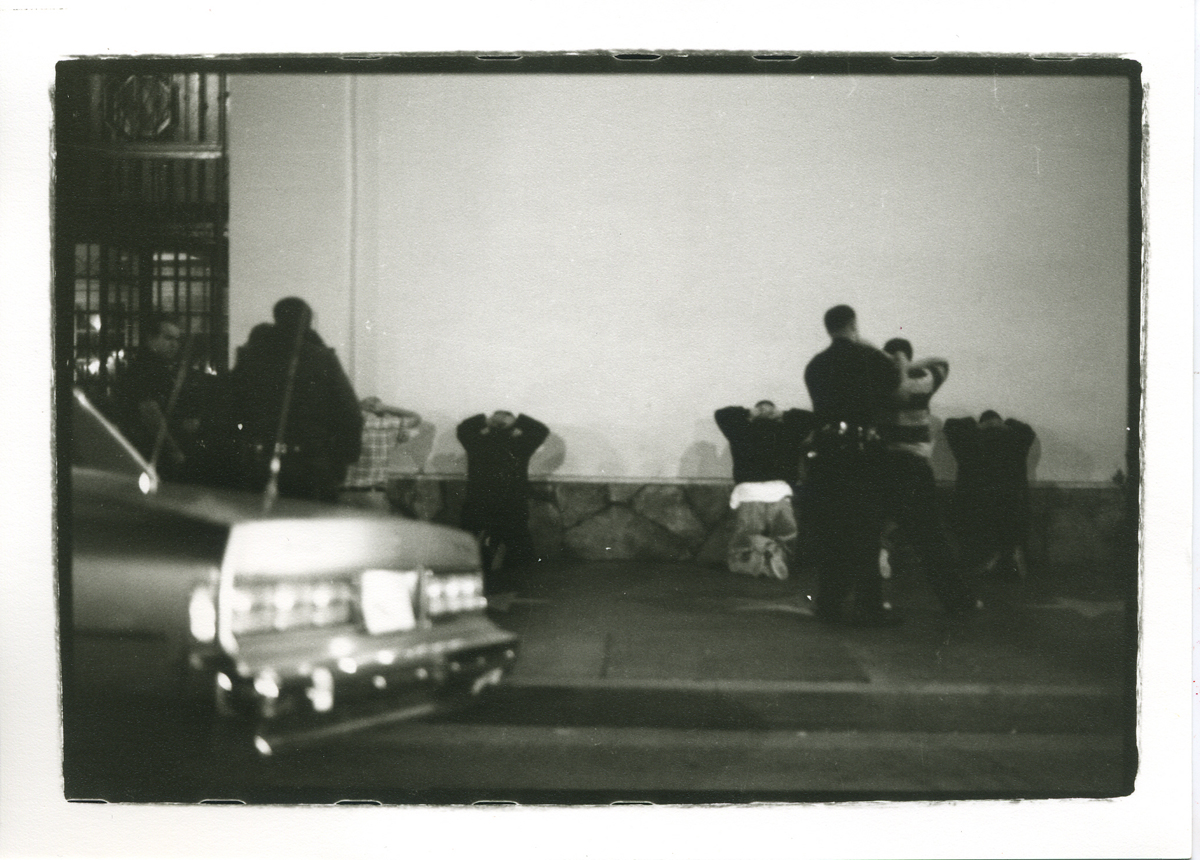

The city exploded in June 1943. For five days and nights, White sailors and soldiers rioted against pachucos. In a ritual of racist violence that spread across the city, mobs of White military men beat zoot suiters, stripped them of their clothes, and left them humiliated in front of gathering crowds. Mexican-American boys as young as 12-years-old were thrashed by American servicemen because of the clothes they wore. The LAPD stepped in only to arrest bloodied and half-naked pachucos. Like a gut punch, the Zoot Suit Riots reminded Mexican-Americans that they were to be treated as outcasts in their own city.

The zoot was a cultural bedrock for future cholo style, which flourished in the 1960s. Fashion was but one note in a cultural medley that captured the revolutionary spirit of the day. Young folk of Mexican descent claimed Chicano as a new identity that rejected Whiteness and assimilation. Instead, they embraced their Mexicano and Indigenous roots, stressing self-determination and political liberation amidst a history of racist exclusion. Their music, lowriders, and cholo aesthetic energised El Movimiento Chicano. Cholo writer Luis J. Rodriguez said as much. “Today’s cholos were an evolution of the pachucos. But by the 1960s,” he argued, “it was a whole new style. I think it was our resistance. It was a resistance to not being assimilated in America, but also not being Mexican because we weren’t really Mexican anymore. We created a third way of being.” The cholo way.

Take, for instance, the Chicano anthem, Whittier Boulevard. Originally released by the Chicano band Thee Midniters in 1965, the song was a citywide hit. An ode to the popular cruising spot, it began with lead singer Little Willie G (Willie Garcia) shouting, “Let’s take a trip down Whittier Boulevard!” Ronnie Figueroa chimed in with a celebratory “Arriba, arriba!” Music critic Ruben Molina observed, “That kind of sets it off and says, ‘This is Mexicano.’ But then, it goes into the surf guitars.” He continued, “You’ll hear influences from surf music to rhythm and blues to Mexican music. It’s basically what the Chicano is: we’re a mixture of Mexican heritage but living in America. It kind of signified: we are here. This is who we are.” Little Willie G described Whittier Boulevard as a call to action “because it was us. And it gave us a voice. You know, sort of like a rallying cry for us to kind of assemble and say, ‘Hey. Are we on the same page?’ And most of us said, ‘Yeah’[9].” Another Chicano band, Cannibal and the Headhunters, covered Whittier Boulevard to national acclaim a year later in 1966.

Whittier Boulevard sprang from LA’s Eastside and was part of a thriving brown-eyed soul scene that blended rock ‘n’ roll, soul, jazz, R&B, and Mexican and Caribbean rhythms. Chicano groups like The Jaguars, The Premiers, and The Village Callers, along with Black crooners like Brenton Wood, ruled the airwaves. Luis J. Rodriguez described them as “the heroes and heroines of lowrider car clubs, street gangs and high school teens. Their records were sold as soon as they came out and whenever they made appearances, they crowded dance halls and concerts [10].” In a 1994 retrospective, the Los Angeles Times described the Eastside sound as “Black soul music strained through Chicano musical roots. Latin rhythm, melodic phrasing and vocal inflection crossed with proto-punk energy levels…[11]”

Lowriders were the visual counterpart. They grew out of Southern California’s postwar car culture and reimagined LA’s urban landscape by reclaiming the streets[12].With exquisite paint jobs and back ends weighted down so they rolled low y slow, they were art and identity exhibits on wheels. Lowered Chevys were canvases filled with representations of Mexican and pre-Columbian culture, from the Virgen de Guadalupe to Aztec warriors. Car clubs emerged as pillars of community. At the same time, in a reprise of the zoot era, lowriders were criminalised. They were linked to gangs and violence, and targeted by police. As early as 1958, California tried to outlaw lowriders by requiring cars to be a certain height above the ground. Lowriders ingeniously designed hydraulic systems that enabled cars to be lowered and raised with the flip of a switch. They could easily change from lowrider to street legal vehicle[13]. With cholo verve, lowriders epitomised what Tomas Ybarra Frausto called rasquachismo, “an underdog perspective—a view from los de abajo. An attitude rooted in resourcefulness and adaptability yet mindful of stance and style[14].”

Cholo style reverberated with El Movimiento Chicano. Inspired by civil rights, Black Power, and anti-colonial struggles around the world, the Chicano Movement was fiercely anti-racist. Activists fought against high rates of poverty, police brutality, and dropouts in Chicano communities. They demanded political control over their own barrios. They believed Aztlán—the territory in Southwestern United States once home to the Aztecs, which was lost by Mexico to the United States at the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848—should be returned to the Chicano people. Meanwhile, Chicanas pushed for gender equality, frustrated that they were expected to bury their feminism in favour of ethnic pride.

LA was a hot bed of activity. Consider the Chicano Blowouts in 1968. More than 15,000 students walked out of their classes at five East LA high schools. They demanded better education to alleviate the 50% dropout rate. The LAPD responded by beating and arresting the students. One need only recall the Chicano Moratorium in 1970. In East LA’s Laguna Park, more than 30,000 people protested the Vietnam War and the disproportionate number of Chicano soldiers killed on the front lines. They chanted ‘¡Raza Si! ¡Guerra No!’ (‘Race Yes! War No!’) and ‘Aztlán: love it or leave it!’ Police unleashed their clubs and tear gas on the crowds, murdering journalist and venerated community voice Rueben Salazar in the melee. Cholo style took hold in this charged atmosphere, its political streak not soon to go away.

Today, cholo style endures. It still runs through the bloodstream of Chicano LA, flowing from the pachuco and Movimiento days to the present. Consider the emotive stories of cholos y cholas since the 1970s.

Sleepy: inspiring, spirited and formidable. She was jumped into the Dukes—her neighbourhood gang in the San Fernando Valley—at just 11-years-old. As a woman in a mostly male clique, she was homegirl, sister, and sometimes mother all at once. Her life in the gang was fuelled by unbreakable bonds of brotherhood and familia. “We were all kids,” she recalls. “We looked up to our veteranos, we were united, we loved each other…” For Sleepy, being chola meant a deep connection with her homies as they walked through life together. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, they explored LA and leaned on each other. Cruising Van Nuys, Whittier, or venturing into Hollywood taught them life lessons. More than 40 years later, Sleepy represents chola culture as an influencer with more than 30,000 Instagram followers (@la_sleepy818). Her spirit and charisma ooze in posts about cooking, cruising, dancing, building community, and being chola. Amongst her greatest joys is when someone tells her, “Hey Sleepy, you inspire me[15].”

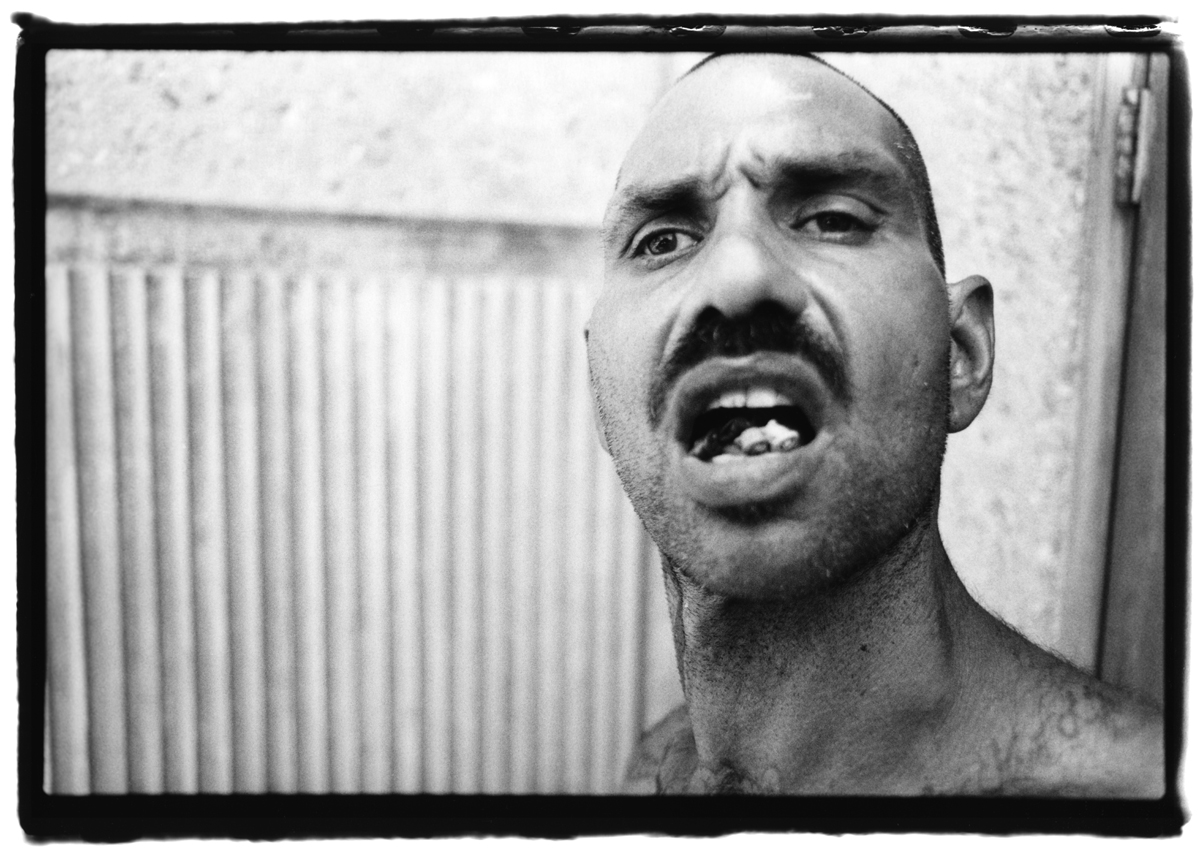

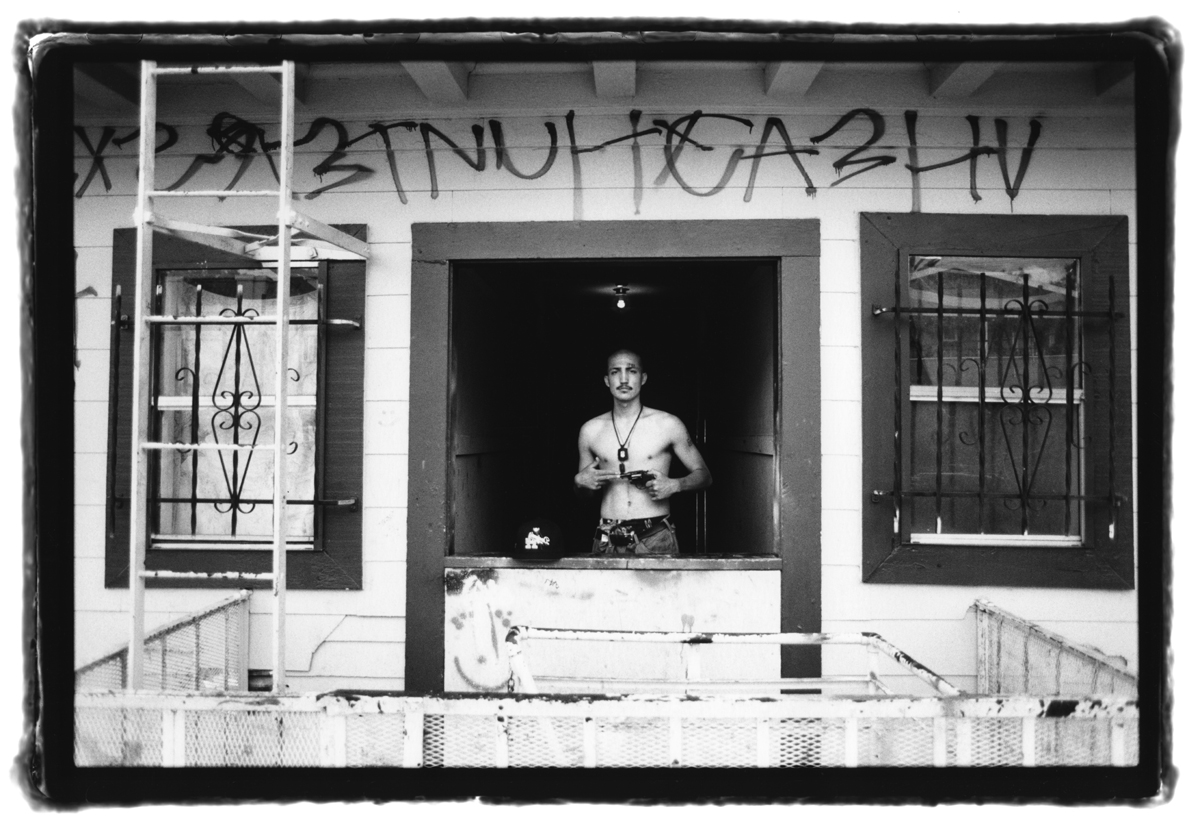

Lepke: resilient, genuine and determined. He is an OG from the Rebels 13 gang on the Westside. The son of a Jewish mother and Sicilian father, he dedicated his life to his Mexicano neighbourhood in the 1970s. For Lepke, gang life depended on a code of ethics that required putting your life on the line. It meant “chewing up them streets” in a life of crime, violence, drug addiction, and multiple prison stints. Recalling his creased-up pants, Pendleton shirt, fedora hat, and Stacy Adams shoes, he emphasises, “Your shit had to be right, or you’d get clowned. You had to look sharp. We looked like 1930s Murder, Incorporated. That was our estilo…” Cholo life was a rollercoaster ride that took him from “the glorious life at the top of the food chain” to shooting heroine on Skid Row. Nowadays, Lepke (@oglepke) has rededicated his life to “helping bring light to La Raza” and is currently writing a memoir about his extraordinary journey [16].

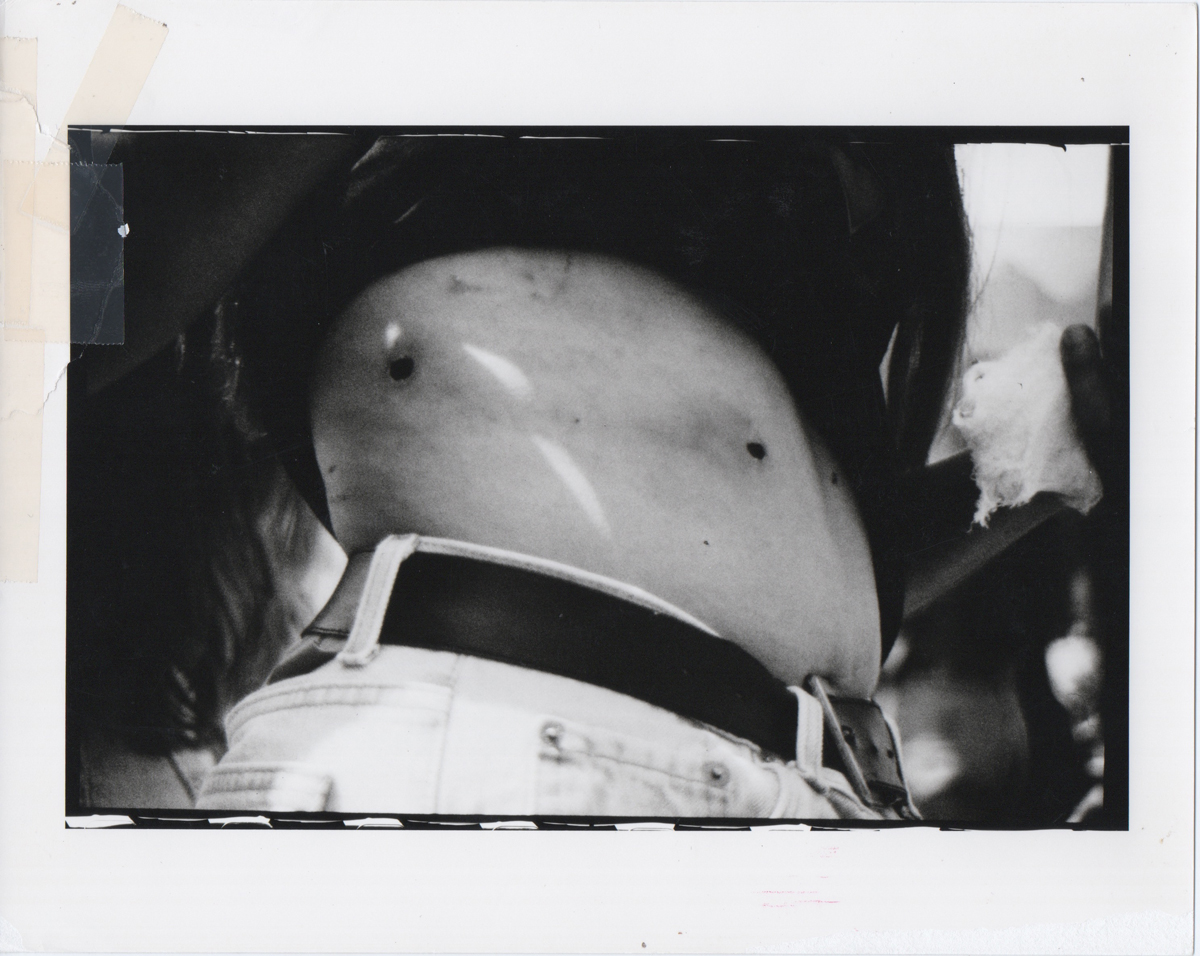

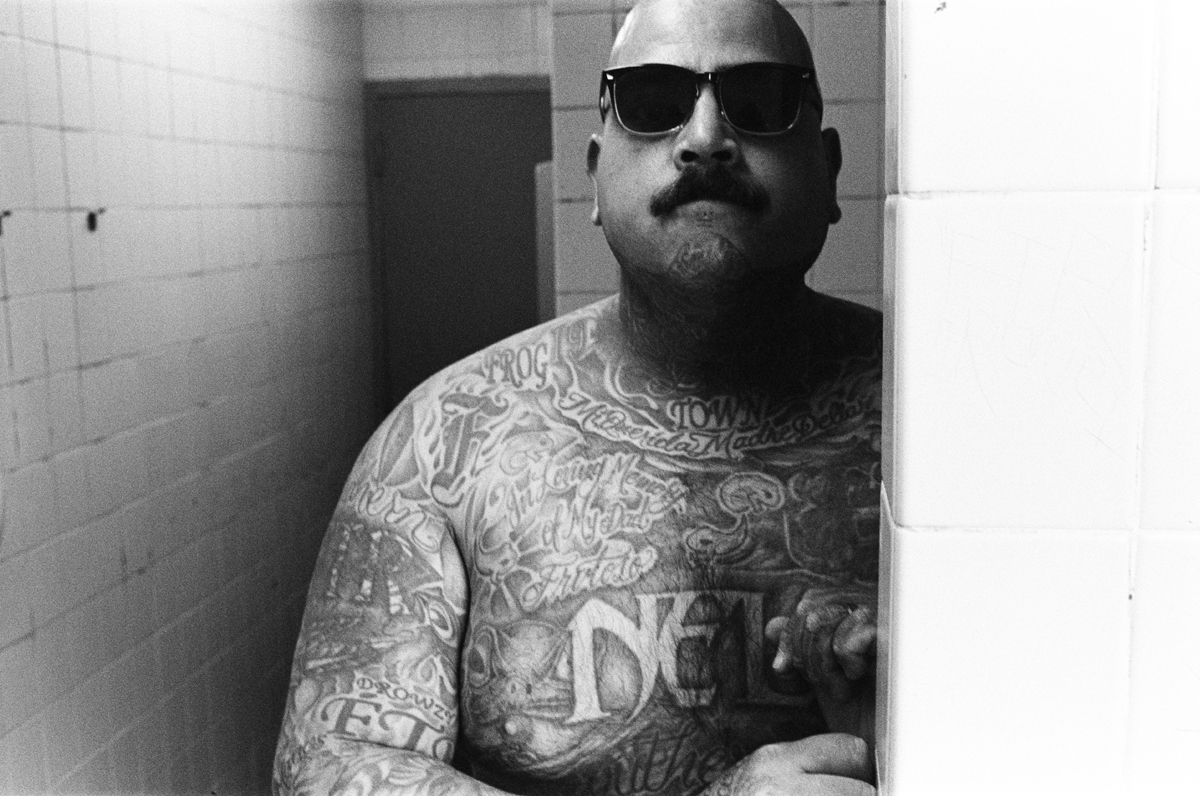

Drowzy: eloquent, authentic and irrepressible. He grew up in the Elysian Valley neighbourhood, known as Frogtown, in the 1990s. Drowzy followed his four older brothers into the neighbourhood gang. He wanted to belong and understood that being cholo “can’t be told or taught. It’s gotta be lived.” His journey took him to “hell and back,” doing prison time and heavy drugs, burying 39 of his homeboys along the way. Through it all, the sweet sounds of brown-eyed soul were a lifeline. A soundtrack to his gang life in the 1990s, he recalls how Brenton Wood or Thee Midniters “soothed me and made me happy.” More than 30 years after they first hit the airwaves, songs like Brenton Wood’s Oogum Boogum (1967) could be heard at red lights across LA. Drowzy “lived on that music to get by.” “People call it soul music,” he says. “Now I know why.” Today, Drowzy works in forestry and his wife and daughters are his “gang[17].”

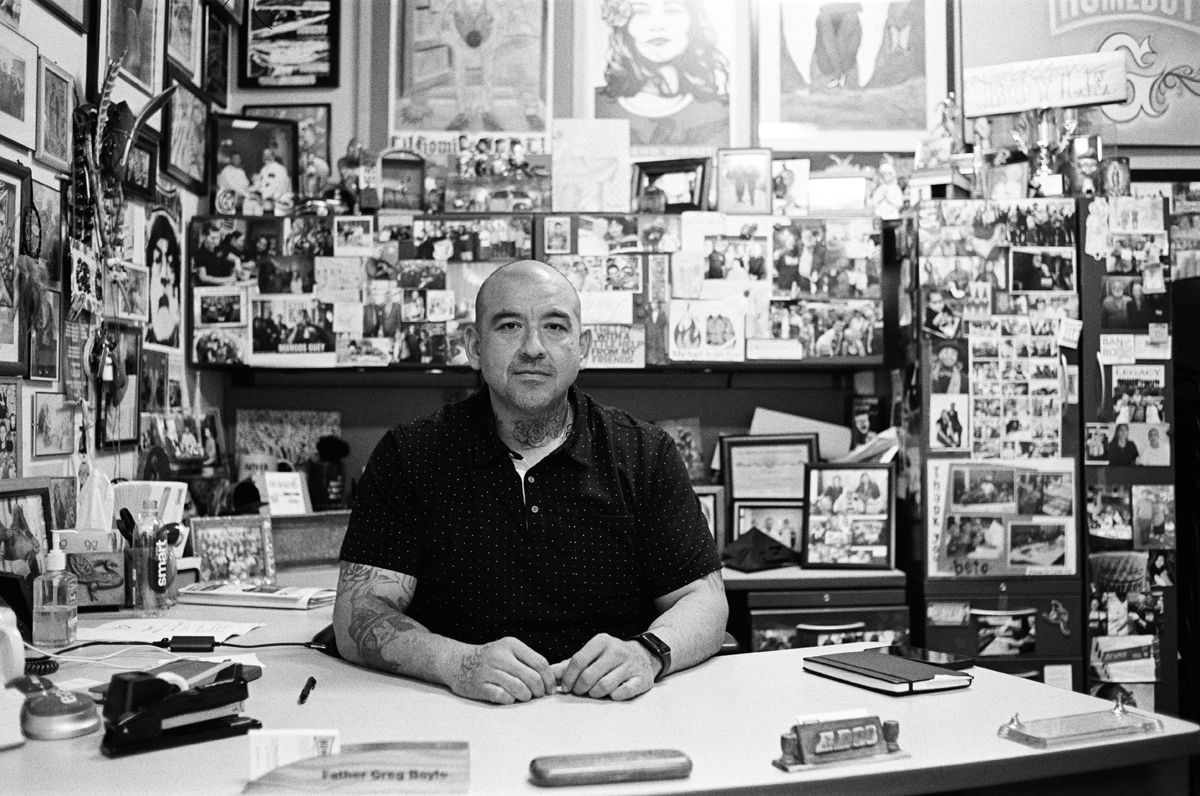

Jose: industrious, dynamic and uplifting. He came from a family of gang members. Joining was a “natural occurrence” and, for him, “just part of being Brown” in LA during the 1990s. Jose grew up poor, but the “lights went off and the power went out” when his mother fell deep into addiction. When he was 12-years-old, he got jumped into his neighbourhood gang, a decision that changed the course of his life. Committing crimes and acts of violence saw him in and out of juvenile hall and prison, driven by what he’d later call the internal colonisation of homies doing harm to themselves and folks who look like them. His cholo style—baggy pants, white t-shirt, oversized sports jersey, Filas, and bald head—was born out of circumstance. When Jose’s mother died while he was in prison, it was a catalyst for change. He came home broken, but landed an entry level position at Homeboy Industries. After cleaning toilets and doing security, he rose up the ranks to VP[18].

For over 30 years, Homeboy Industries has been “the largest gang rehabilitation and re-entry programme in the world [19].” Founder Father Greg Boyle captures its mission: “we imagine a world without prisons and then we try to create that world[20].” The organisation has more than 450 trainees that are former gang members or incarcerated people, including many violent offenders with complex traumas. It has a staff of 180 people, 75% of whom are former clients, and serves 10,000 people a month through its apparel and merchandise, bakery, cafe, dog grooming, electronics recycling, and other enterprises. As Jose says, “Homies and former gang members are now therapists and substance abuse counsellors.” In 2024, Father Greg and his team were awarded the Presidential Medal of Honour at the White House for their work. Closer to home, the city of LA recognised May 17 as ‘G Day’ in their honour. For Homeboy Industries, cholo is a story of resilience and transformation.

Like the pachucos before them, cholos traversed an unforgiving urban landscape. In the 1980s, the deadly combo of deindustrialisation and Reaganomics struck LA hard. Unionised factory jobs disappeared, unemployment skyrocketed, and housing and healthcare were increasingly unaffordable. At the same time, Black and Latino neighborhoods were militarised by police during the crack epidemic and The War on Drugs. Cholo culture and gangsta rap chronicled the moment. Predictably, as historian Mike Davis argued, “a volcano of Black rage and Latino alienation erupted in the streets of Los Angeles” during the 1992 uprising that followed the acquittal of four LAPD officers who beat Black motorist Rodney King[21]. Davis described the violence as “a postmodern bread riot” that, like cholo style itself, was a response to civil rights violations, impoverished conditions, and inter-racial conflict [22]. Just two years later in 1994, California’s anti-Mexican sentiment escalated. White fears of a ‘majority-minority’ state and the ‘browning’ of the population sparked the anti-immigrant legislation, Proposition 187. It targeted undocumented immigrants and fuelled what historian Rachel Buff called the “deportation terror.” It also sparked sweeping animus against anyone of Latino descent[23]. LA in the 1990s was a canary in the coal mine. Viewed from the streets, it forecast the demonisation of Latinos into the 2000s and the Trump era.

Cholo style is still louder than the hate. As Mister Cartoon reasoned, “That violence, that poverty, that madness spawned a beautiful art form of music, and tattoos, and wall murals, pinstripe and gold leaf…[24]” There isn’t one cholo, but many. Cholo is a transformative journey through Chicano history and across generations. It’s perseverance feeds off the most difficult of circumstances. And, while cholo style, lowriders, and music have spawned scenes in Tokyo, Berlin, Barcelona, Mexico City and places beyond, LA remains it’s beating heart. What does LA mean in this cholo story? Jose calls it the “city of hope” and “the gang capital of the world.” Drowzy says, “LA is respect, it’s culture, it’s real, it’s love. It’s my home.” Lepke echoes, “LA is my stronghold, spirit, and life. My blood is embedded in its concrete. LA is like love. LA is my heart.” Sleepy similarly testifies, “When I pass on, I want to come back to LA. It’s love. LA is a part of me.”

Cholo style is an LA creation. It grew from the city’s long history of Chicano struggle and is a product of its own radical history. It’s survival and defiance live on. As Sleepy, the veterana chola, poignantly declares, “I am glad we’re sharing our story with the world. Aquí estamos.” We are here[25].