The three auteurs profiled in this piece—Janicza Bravo, Raven Jackson and Darol Olu Kae—are amongst the most exciting voices working in cinema today. Though their styles and approaches differ, they are united in their refusal to conform to industry expectations, pushing the boundaries of form, narrative and representation.

Ever the provocateur, Bravo bends expectations with darkly comedic narratives that bring to mind films by Melvin Van Peebles and Spike Lee. Wide-ranging in subject material, her ‘stress comedies’ observe the absurd lives of miscellaneous fictional characters, from a paraplegic in Gregory Go Boom (2013) to a stripper in Zola (2020) to an English teacher in The Listeners (2024). The tenderness of Jackson and Kae’s films, on the other hand, explore more intimate narratives, woven together with autobiographical elements. Privileging texture and atmosphere over conventional plot, Jackson crafts quiet and immersive films with a lyricism that recalls Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep and Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust. Although fictional, the protagonist of Jackson’s feature film All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt (2023) shares parallels to her own experience of coming of age in Tennessee, United States, where parts of the film were shot. Meanwhile, Kae’s short film Blur (2025) breathes life into personal memories intertwined with poetic references in an ode to his uncle who died of AIDS. Blurring the boundaries between time, memory and sound, Kae’s earlier projects, such as i ran from it and was still in it (2020), Infinite Tapestry (2022) and Keeping Time (2023), further reflect his tendency as a researcher, diligently splicing archival footage and real-life conversations with original material in dialogue with the contemporary works of artists Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph and AG Rojas.

Despite a shared understanding, each has crafted a singular vision. Rejecting the generalised portrayal of Black life, Bravo, Jackson and Kae’s films collectively demonstrate an expansive and nuanced Black specificity that acknowledges the distinct cultures, experiences and identities of individuals within the diaspora. Reclaiming agency and self-definition, Jackson renders Black life with an intimacy of gesture and touch rarely seen onscreen while Kae pushes back against reductive tropes such as the tortured Black artist. Less inclined to wait to see her own image and likeness represented onscreen, Bravo alternatively seeks to see herself in the universality of “feelings, colours, shades and smells.”

Janicza Bravo

Writhing and fumbling through scenarios so uncomfortable they make you want to cover your eyes, Janicza Bravo’s characters never land where you think they will. A trickster through and through, narratively she’s always shaking things up; she likes keeping her audience unsettled and on their toes until the very end. Her world is delightfully off-kilter, absurd and hyperreal, her sense of humour as black as coffee. Bravo is concerned with only the rawest of human states and feelings—desperation and despair, envy and greed. Stress comedy, as she likes to call it.

Take Pauline Alone (2014), for example, a short film in which a woman, played by Gabi Hoffman, tries to connect with strangers through missing pet advertisements but only ends up terrorising them. Or Gregory Go Boom (2013), starring Michael Cera, in which a lonely and bitter paraplegic goes looking for love but only finds shame. And, of course, there’s her critically-acclaimed second feature Zola (2020), a perfect rollercoaster of a film that Bravo once described as David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) meets Cardi B’s Bodak Yellow, in which a titular character falls down a rabbit hole of madness after she agrees to go on a spontaneous road trip to Tampa for a stripping gig.

Based on a series of tweets by A’Ziah ‘Zola’ King and an article in Rolling Stone, Bravo penned the screenplay with playwright Jeremy O. Harris. The result is a genuine masterpiece. Bravo gives King and her story, so easily mishandled, loving attention. Only a filmmaker like Bravo could hold such a dizzying story so deftly, taking its audience on a journey that entertains but also haunts.

Bravo, who studied theatre directing and design at NYU, is a theatre director at heart. After graduating, she moved into styling. Her work as a stylist becoming a vehicle for her work as a director, as she continued to direct plays on the side. She started making shorts after she sent a screenplay to a cinematographer who had reached out to her after seeing her staging of August Strindberg’s Miss Julie. Bravo worked tirelessly from there, writing 10 short films in less than a year and vowing that she’d make every single one. This tireless work paid off. Today, Bravo has two narrative features under her belt and multiple credits as an actress and director for television.

Her latest project is The Listeners (2024), a television series based on the novel by Jordan Tannahill. The Listeners follows Claire, an English teacher who becomes increasingly tormented by a mysterious humming noise that no one else seems to be able to hear. Although Claire learns that she’s not the only one able to hear the noise, her loved ones continue to dismiss her.

“I’ve had my share of experiences of not feeling all the way heard or validated,” says Bravo on why she was attracted to The Listeners. “That felt close to me and something I wanted to exorcise.” Bravo directed all four episodes and spent a little over two years working on the series. As a straight drama, The Listeners may seem like a departure for Bravo, but as a theatre director she primarily worked in drama. “I wondered, because it had been a while since I’d been in that realm, if it was still available to me,” Bravo says.

I ask Bravo where her sense of freedom comes from in regards to the subject material she chooses. “It all comes down to ‘Where is my spirit moving?’,” she tells me. “With everything I work on, I am all of the people,” says Bravo. “I see some version of myself in all of them. [With] so much of the stuff I’ve watched and gravitated towards, almost never was the protagonist someone made in my likeness.” Freely borrowing from Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Jon Fosse, Françoise Truffaut and John Cassavetes, Bravo never waited to see herself on screen. “I just learnt to see myself in feelings, colours, shades and smells.” Instead, she’s made the medium and system work for her, flinging the doors wide open as she marches her way through.

Bravo’s work raises intriguing questions over ownership and identification when it comes to race and gender. ‘Is X person allowed to say Y?’ ‘Should a film be defined by who comprises it?’ Bravo received some criticism early in her career for the ‘whiteness’ of her films. (She once joked that Zola was her ‘coming-out-as-Black’ film.) Lemon (2017), her first feature, starring her ex-husband, the comedian Brett Gelman, follows a dysfunctional Jewish man after his girlfriend of 10 years leaves him.

“Lemon was so much about the fear of failure,” says Bravo. “The fear of waking up one day and life having passed you by.” She co-wrote the film with Gelman, a frequent collaborator. “We were looking ahead and going, ‘Oh, God. Am I going to arrive at the thing that’s meant for myself? What does that look like?’ The film was a little bit like witchcraft. You make the thing and then you light it on fire and then it means it won’t happen to you.”

I ask Bravo what’s next for her. She tells me she can’t say much, but there are plenty of exciting projects in the works. “I’m just finishing a script right now,” she says of an upcoming feature. Getting her own work produced has been challenging. “It’s ultimately because people are risk averse and I’m working deeply left of centre,” Bravo says.

“It’s about ease,” Bravo tells me when I ask what she’d make if she had no constraints. “I am not afforded ease. I do have to do a lot of heavy, heavy lifting to convince people that I think I am a worthwhile risk,” she says. I imagine that’s a heavy burden to hold. “The thing that does make things feel a little less fucked and worthwhile is that if it’s hard for me now then it means it gets to be a little easier for someone else later. So if I can take it, if I can get through the exercise, then it means I’m just making the path a little smoother for the person behind me, as I imagine someone has done unknowingly for me.”

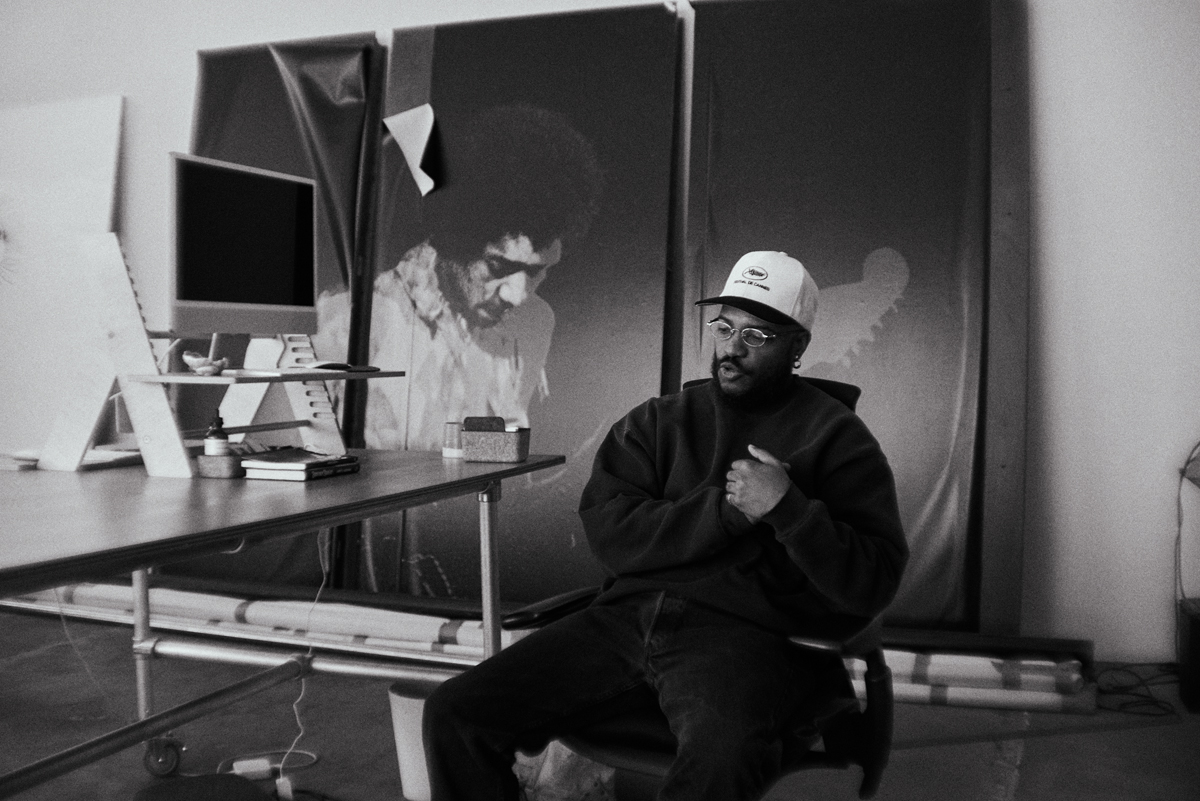

Darol Olu Kae

You can’t talk about black without talking about blue. Miles Davis playing in the belly of a sweet midnight, moonlight running across his face—or the magic Lorna Simpson is able to create with the colour blue, rendering it iridescent and arctic.

Filmmaker Darol Olu Kae’s short film Blur (2025) is filled with blacks and blues. An homage to poet and scholar Fred Moten’s book Black and Blur, the first work in his trilogy consent not to be a single being, Blur opens on a frame of Gloria, played by Jacqueline Frazier and Kamara McDaniel, at a bus stop. Memories of her late brother Dre, played by Michael Rowles, arise as she waits. ‘I just don’t have enough,’ Gloria thinks, considering the photographs she has left of him. ‘My favourite pictures of him live in my memory,’ she decides.

The film is an ode to Kae’s uncle, who died of AIDS when Kae was young. Breathing life into memories, the film reflects on how Kae’s mother would travel across Los Angeles to help him wash his hair. This act of care left a profound impact on Kae. Blur, Kae says, is about touch. The film is full of tender embraces between Dre and his sister, his lover and his friends. Touch becomes an antidote, a salve against stigma and shame.

Like much of Kae’s work, Blur concerns itself with the fugitive, that which cannot be easily contained or captured. For Moten, blue is a fugitive pigment, a hue that forever eludes. In Blur, Dre runs inside the blues, his body slipping through time. Death must come but Dre knows there’s no use in looking for him. And so he runs—dodges, blurs—evading capture. Content not to be still, content not to be a single being.

“Perhaps there’s a portraiture that disrupts the face, and the face to face, while calling us to prayer?,” wonders Moten in his essay Blue Vespers. This question presents itself throughout Kae’s films. “There’s something about displacing or decentering sight that I find interesting,” says Kae. As a filmmaker, Kae is deeply invested in sound. Jazz is a recurring obsession and often the subject of his films; he is a devoted student of its history and seeker of its greatest practitioners.

You can’t talk about jazz without talking about death. “I’m very fascinated by when traditions die or are on the verge of extinction,” Kae says. “The question is always, ‘Is jazz dead?’ ‘Is this thing anachronistic?’ We’re living in a world where a lot of folks associated with free jazz are no longer here. A lot of them are passing away. Jazz opens up the larger question of, ‘What are the traditions we claim?’ ‘What are the traditions we let die?’ It’s [part] of the Black experience, too. How do we honour the past but also make something new at the same time?”

Kae probes these questions in his short film Keeping Time (2023). The film follows real-life drummer Mekela Session as he struggles to unite members of The Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, an intergenerational avant-garde jazz band founded by legendary jazz pianist and composer Horace Tapscott in 1961. The film is a multilayered tapestry of original and archival footage based on Kae’s in-depth research and real-life conversations that took place between Session and other members of the Arkestra.

“I wanted to make a film as complicated and multi-directional as the band,” says Kae on the film’s kaleidoscopic nature, pushing back against the tropes in jazz he saw as reductive—the tortured artist who uses drugs to create, the emphasis on performance. “Why is the dominant image of jazz about people in a smoke-filled jazz club?,” offers Kae. “I want to force people to confront the complicated beingness of Black musicians outside of their musical production.” There’s no big show or dramatic blow-out in Keeping Time. Instead, Kae withholds, keeping us inside the space of rehearsal, community and improvisation. For Kae, the Arkestra offers a powerful model of sociality, a way of living that is about “coming together without capital incentive or outcome.” In 2022, he filmed members of the Arkestra for Infinite Rehearsal, an installation that reconstructed the group’s rehearsal space.

Kae grew up in Southern Los Angeles. Only after he graduated did Kae learn that Tapscott attended his high school, Jefferson High. It urged him to look more closely at the rich cultural traditions that surrounded him. “People like to reduce Black traditions and Black specificity,” Kae tells me. “Why can’t Black specificity be a place of the universal?,” he offers, referencing a quote from artist Arthur Jafa.

Kae’s practice as a filmmaker is in conversation with local filmmakers like Jafa, Kahlil Joseph and AG Rojas. Kae’s foray into filmmaking began in part through his collaboration with Joseph on BLKNWS (2018-), an ever evolving two-channel installation that “blurs the lines between art, reporting, entrepreneurship, and cultural critique.” Kae helped shape and develop BLKNWS, working as a researcher, writer and editor. Seeing Jafa’s Love is the message, the message is Death (2016) was also a critical moment for Kae, who was astounded by Jafa’s use of found footage. Kae’s first short film i ran from it and was still in it (2020), a gripping meditation on paternal loss, familial love, and inheritance, emerged from these experiences. The film won the Golden Leopard for Best International Short Film at the Locarno Film Festival in 2020 and received the Special Jury Recognition for Poetry at the SXSW Film Festival in 2021.

Kae’s first feature Without a Song (TBA)—described by Kae as “a ‘closing-of-age’ film”—is in development with Jafa’s film production company, SunHaus. Without a Song begins in Copenhagen, where the audience will meet an elderly Black musician who has lost his ability to play his instrument. The musician is forced to return to Los Angeles, where he must confront his past and the principles he once played about.

“It started from the Arkestra,” explains Kae. “I would read about or hear conversations where [members] would mention people passing away or committing suicide. They would say, ‘They were just too sensitive for this world.’” Kae started looking for some of these titans of free jazz, many of whom had left for Europe in the 1960s and 1970s and never returned. Or sometimes, as was the case with saxophonist Giuseppi Logan, reappeared on the scene 20 or 30 years later. Paris and Copenhagen—nicknamed ‘Copenhaven’—were popular destinations.

Without a Song engages with the Black expat tradition and the age-old question of whether or not America is worth coming back to. Kae travelled to Copenhagen to research the film. There he met up with a jazz musician who was living on a boat and just so happened to be a former member of SNCC who once served as Miriam Makeba’s personal bodyguard.

“Have you seen the murmuration of birds?” Kae asks me. “They became an analogy, a metaphor for Black musical expression, especially jazz,” he says. Kae equates the murmurating birds to jazz musicians playing. “It’s beautiful but the reason the birds are moving like that is because they’re evading birds of prey above them. For me, that’s the best image to represent jazz. The music is only happening within the context of being under siege in America. We can’t detach jazz from the social experience that produces it.” If so, Kae’s keeping watch, his gaze close and careful. “It’s critical because these people are passing,” he adds after a moment. “It’s history. And no one is going to do it besides me.”

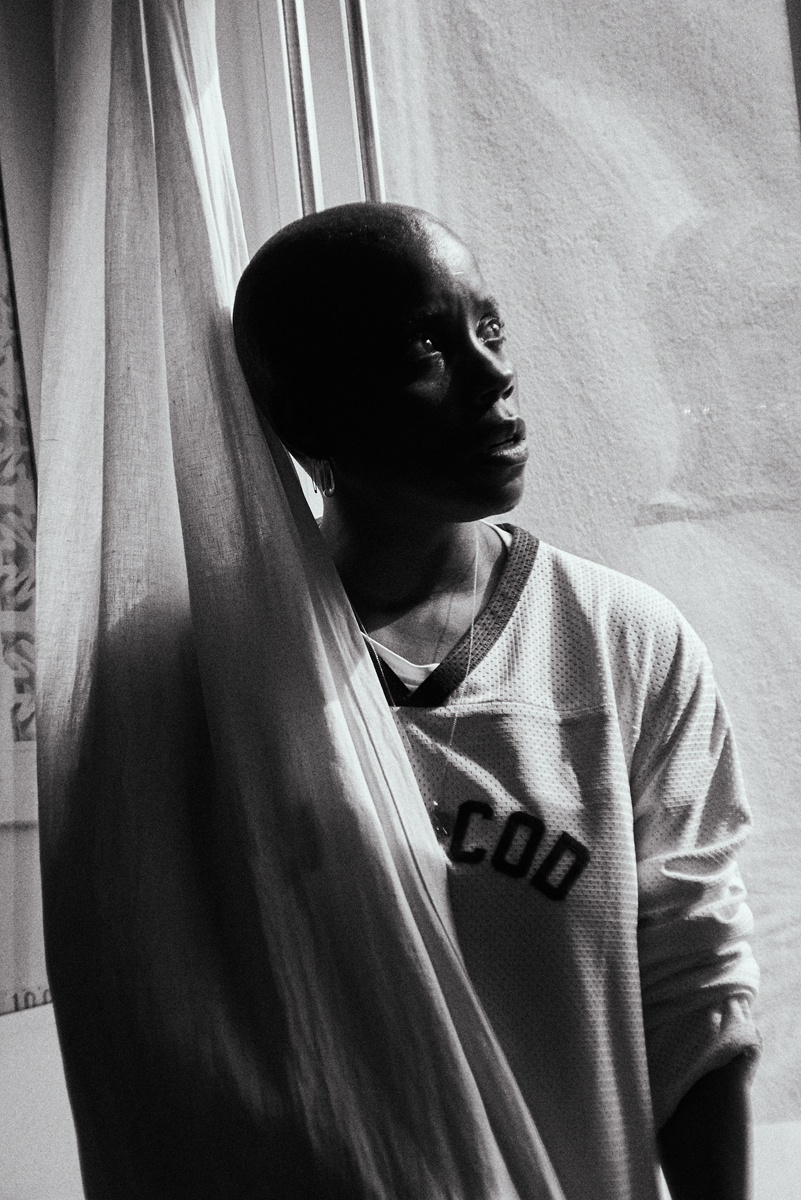

Raven Jackson

Some folks are so close to the land that they eat it. A hunger for peat draws them to the soil, the taste of salt heavy on their tongues—especially Southerners, for they know how much history the land holds. They carry that history in their bodies, hands and faces, the land as close as kin.

Filmmaker Raven Jackson breathes life into this closeness in her graceful debut narrative feature All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt (2023). All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt follows a young woman named Mack, portrayed by phenomenal actresses Kaylee Nicole Johnson and Charleen McClure, as she comes of age in Mississippi. The film’s title comes from a poem by Jackson, who also wrote the film.

“As a person, I’m very interested in the textures of our lives, the moments that seem small but you think about years later,” says Jackson. “I always knew I wanted to focus on some profound moments in this character’s life but also the quieter ones, the ones where you’re looking at what your grandma’s hands are holding. I wanted to give those mundane moments equal weight to larger ones, like the loss of someone you love.”

The film weaves through time, drifting from Mack’s youth to adolescence to adulthood in no particular order. The story of her life is told through the most intimate of gestures and touches: her hands on a fishing line as her father guides her through a catch, a long embrace with a lover. Hands are a recurring motif. “I love hands,” Jackson says. “I love details. I love the body. For me, the hands are right up there with eyes. But it was a discovery of just how much hands wanted to take up space in the film.”

Although All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt is fictional, it contains many autobiographical elements. Jackson is from Tennessee and like Mack grew up fishing. (Her father’s tackle appears in the film.) Jackson’s a Southerner through and through, suffusing the film with textures and sounds only Southerners like herself know intimately—the slow croaking of frogs and the gentle whirring of katydids.

Cinematographer Jomo Fray, who recently received acclaim for his work in Ramell Ross’s Nickel Boys (2024), shot the film. Jackson and Fray collaborated previously on Jackson’s second short film Nettles (2018). “It was nice to have that background with Jomo before coming to a feature because it prepared us for this film,” says Jackson. Like All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt, Nettles plays with structure and lingers on the quieter moments of life. “We still had to grow and stretch ourselves but that foundation made it an easier transition. I’m really grateful for the history we have.”

The trust between Fray and Jackson makes itself clear on screen, each scene beautifully rendered, unfolding like a memory. A sense of deep presence pervades the film. Jackson and Fray would often go on walks between setups while shooting. “It’s important, for who I am, to set aside time to really locate [myself] in the feeling of it, on what [I’m] going for emotionally and why [I’m] even here,” says Jackson. “Jomo and I are really good at that, and also stretching ourselves. Neither of us were interested in just executing a shot list.”

Fray wrote a manifesto for All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt, which included guidelines like ‘Be present to the cinema happening on set’ and ‘Stay elemental.’ “The manifesto really opened us [up] to the magic happening before us,” Jackson adds. One of Jackson’s favourites was: ‘The wound is where the light gets in. Embody it in every frame,’ drawn from a poem by Rumi. “It really made me think about the treatment of the light.”

Jackson cites the sensuality and strong atmosphere of The Scent of Green Papaya (1993), directed by Tran Anh Hung, as a major reference. “I feel the weather in that film,” says Jackson. The same can be said of All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt. Carlos Reygadas’ Silent Light (2007) also served as a source of inspiration for the film’s sound design. “The sound design of that film is so rich,” Jackson says. “In thinking about how I wanted to treat the sound, that’s a film that really came to life for me.”

All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt’s arresting imagery and careful attention to detail also recalls Julie Dash’s pivotal film Daughters of the Dust (1991), shot by artist Arthur Jafa. Like Dash, Jackson uses a poetic framework to explore the interior lives of her characters, creating a film one doesn’t merely watch but rests inside of, drawn in deeply by the specificity of its sounds and the quality of light found within it.

The release of All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt announced Jackson as a critical new voice in cinema. The film was nominated for a Film Independent Spirit Award for Best First Feature and Gotham Award for Breakthrough Director. A24, a co-producer of the film, published a companion book, Stories From a Place Where All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt, which features Jackson’s photography and writing from Kasi Lemmons, Kiese Laymon, Charleen McClure, and others. “It’s been a joy welcoming All Dirt Roads [Taste of Salt] into the world,” says Jackson. “But I’m ready to continue to build new things and see more projects come to fruition. It’s an exciting time full of a lot of potential.”