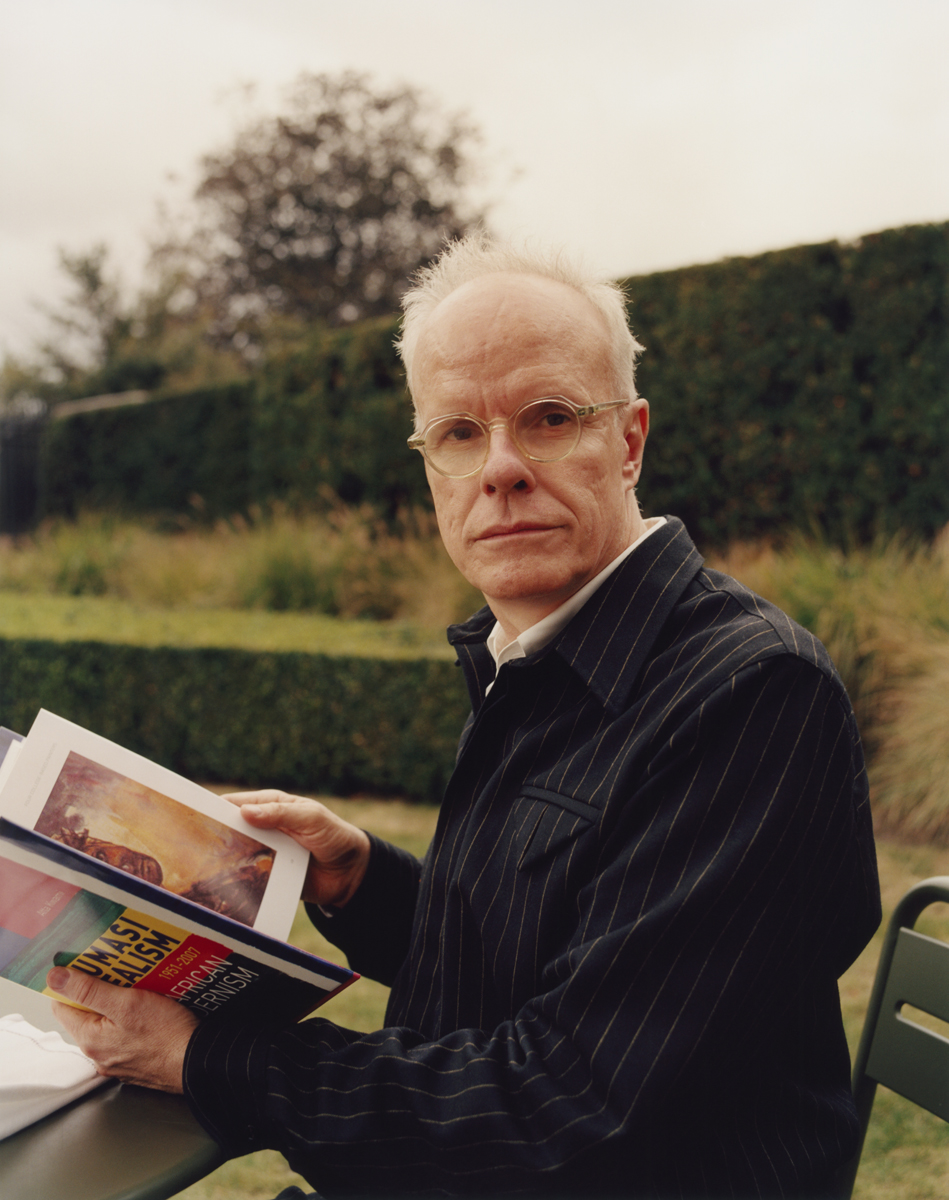

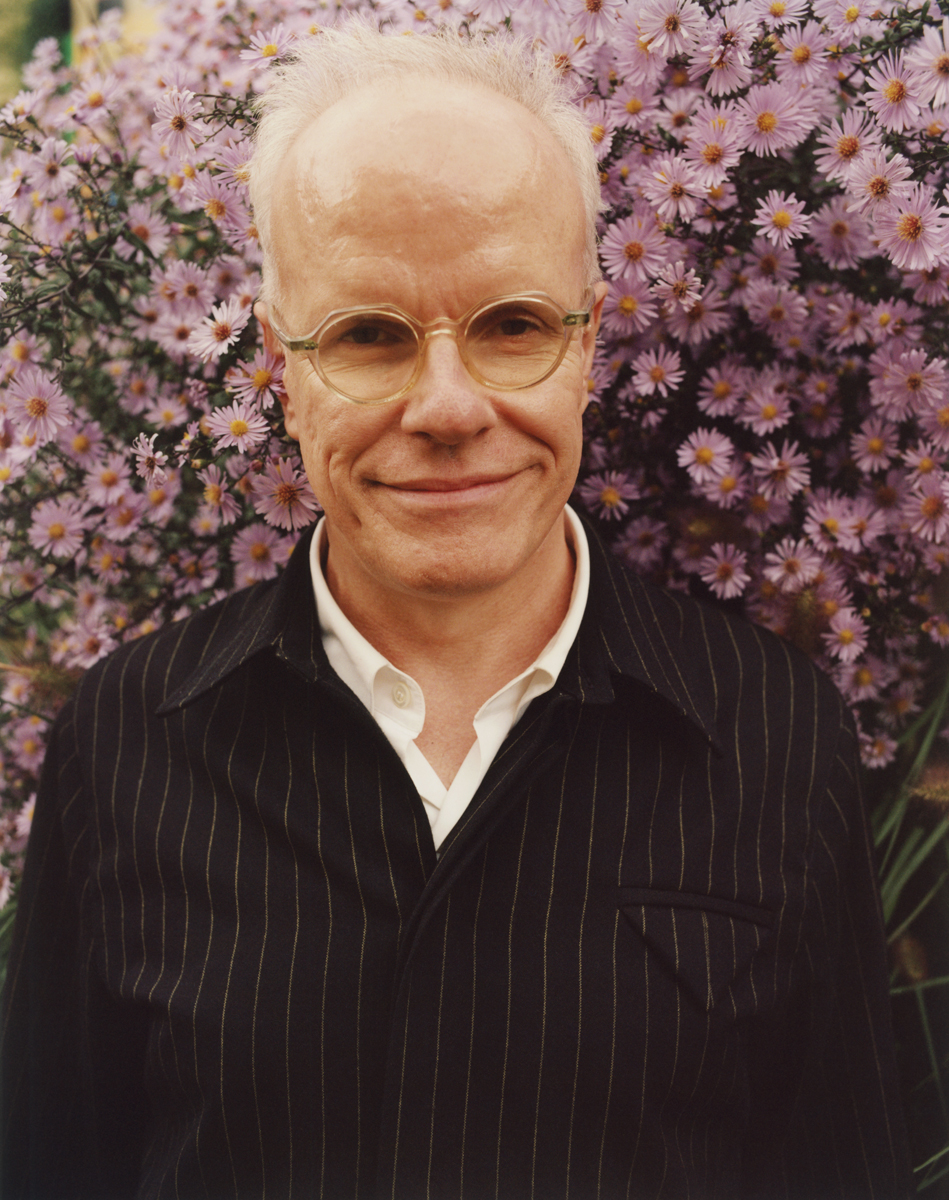

For curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, new exhibitions and collaborative projects often evolve from conversations. In a world where the term “to curate” is stretched to its limits—whether for a social media feed, a dinner party, a shop layout—the notion of curation through conversation is the best way to describe how Obrist works. Since the mid-1980s, as a teenager growing up in Switzerland, Obrist has been talking, meeting, plotting, and planning with artists, as well as visiting exhibitions and studios nonstop.

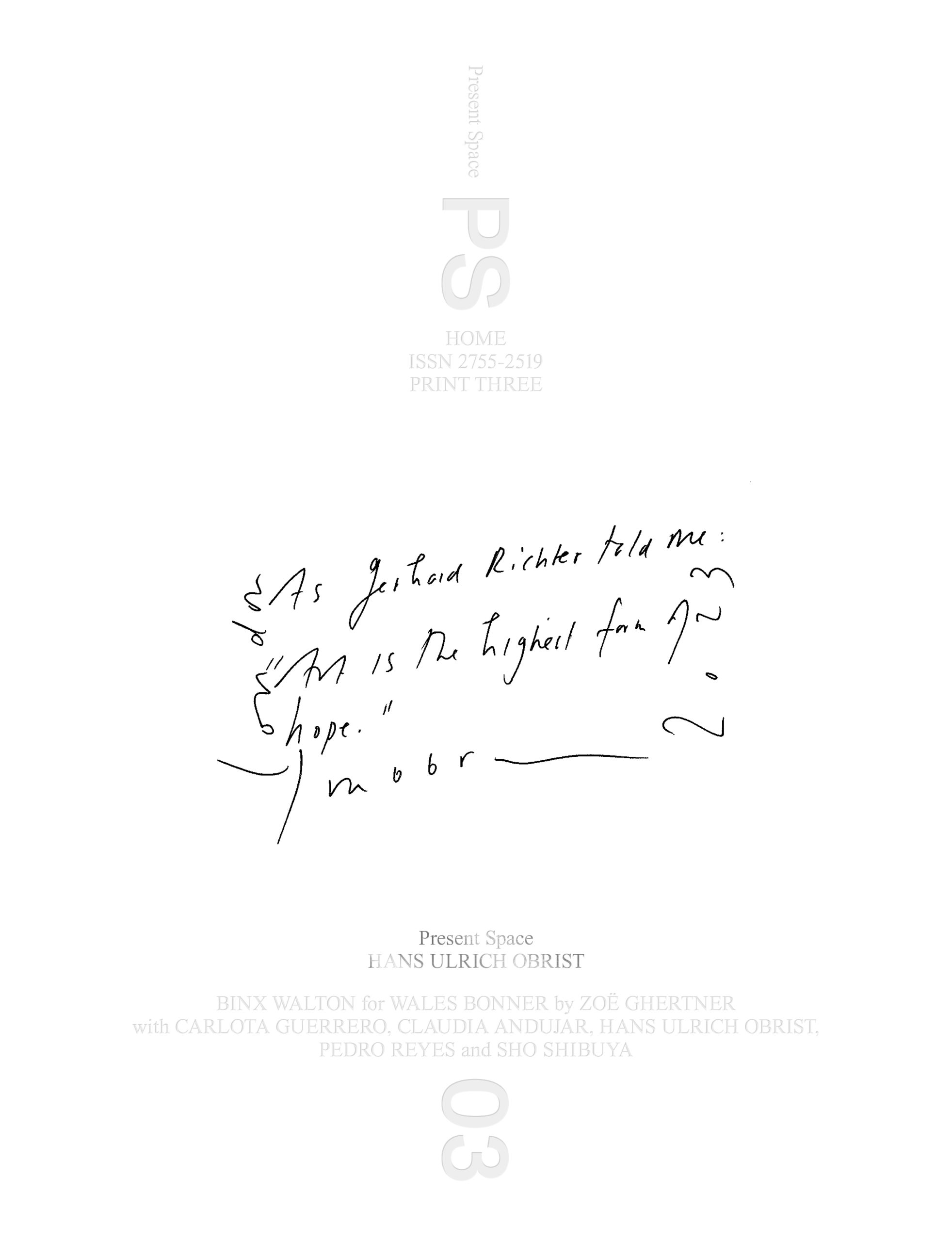

Some of his formative visits with artists continue to shape how he works today. This is evident from reading Ways of Curating (2014), a book as much about curating as it is about the ideas and encounters that have shaped Obrist’s worldview. For example, a visit to the studio of Swiss artist duo Fischli & Weiss is described by Obrist as the eureka moment when he knew he wanted to curate exhibitions. One of the first was of Gerhard Richter’s work, whom he had met as a 17-year-old (a quote by Richter appears in this issue of Present Space). Meanwhile, the artist Aligihero Boetti had encouraged Obrist to ask artists about their unrealised projects—something Obrist continues to do. When Boetti died in 1994, Obrist decided to begin recording his conversations with artists, aware that his time with Boetti had been undocumented and would remain only memories. These are just a few examples of how his encounters with artists have, in turn, shaped the curator that Obrist is.

In 1991, Obrist staged World Soup, a group show in the small apartment he rented as a student in St. Gallen. Eager to exhibit works by Fischli & Weiss, Christian Boltanski, and others, he chose a space that he had immediate access to: the unused kitchen. Two years later, he staged another group show with a similar premise, this time in room 763 of the Hotel Carlton Palace in Paris. “I’ve always been interested in the blurring of art and life,” Obrist says to Present Space over Zoom. “I invited 70 artists to exhibit and create this Gesamtkunstwerk in my little hotel room, and they created very intimate works that artists would never do in a museum.”

Early exhibitions such as World Soup demonstrate a resourcefulness and enthusiasm for creating and curating wherever and however—this concept of staging shows in domestic settings is something that Obrist has continued to explore. In 1999, he staged Retrace your steps: Remember Tomorrow, a group exhibition with Cerith Wyn Evans, Steve McQueen, Rosemarie Trockel, and others at the Sir John Soane’s Museum in London. Before the architect and collector died in 1837, Soane had worked towards establishing the museum in his home. As such, Retrace your steps is an exploration of the notion of home as museum.

The experience spurred Obrist to stage more exhibitions in home museums, compelled by the thought of “all these extraordinary house museums that we could inhabit.” One such exhibition was The Air Is Blue, conceived in collaboration with Pedro Reyes. As the artist recalls to Present Space, “Hans Ulrich was visiting Mexico, and I told him, ‘There’s a place you should visit.’ I took him to Casa Barragán, which back then had just started to receive visitors.” This was the beginning of a series of artistic interventions in the home of the late architect Luis Barragán, staged between 2003 and 2006. Artists who participated in the project include Olafur Eliasson, Dan Graham, and Rem Koolhaas. House museums, Obrist says, are like “conversation pieces.”

Today, Obrist is the artistic director of the Serpentine in London, where he has worked since 2006. The gallery attracts shows by world-renowned international artists, with upcoming solo exhibitions in 2024 featuring Barbara Kruger, Judy Chicago and Yinka Shonibare. The recorded conversations he’s been making since the mid-1990s have been published in an extensive collection of books, while the archive of his interviews is now held at the LUMA Arles in France. As well as curating and writing about the art world, Obrist has also spent the past decade using his Instagram to share a series of Post-it notes handwritten by the artists he’s met. In autumn 2023, 100 of these notes—from artists, architects, designers, and entertainers—were published in Remember to Dream!, the first volume in a series of books that could be endless. “There are thousands of [notes],” says Obrist, “so there can be many more volumes to come.”

In a way, I don’t have one definition because it keeps changing. I’ve always lived between geographies, and I would say home is a triangle between London, where I work at the Serpentine; Switzerland, where I started and always return; and Arles at LUMA, where all my books are. And I think what is important is that these places are connected by train. If the home is scattered over different places, or different aspects of the home are scattered, I think it is important that we find a way of connecting it by train. Europe is in a position to do that, because the distances are not so big; we just need more night trains. In a way, night trains have maybe been my ultimate home; I would say some of my key experiences—thinking, reading, encounters with people—happened on night trains. I love to work on night trains. I love to sleep on night trains.

Of course, the Serpentine is a former teahouse, so I actually work in a house. It’s a Kunsthaus, and I spend much more time here than I spend at home. I come here at 8am and leave at the very end of the day. Something that Marina Abramović always said when she took over the Serpentine [for 512 Hours in the summer of 2014] was that she got the keys to the house. The same is true for Tomás Saraceno—with Web(s) of Life (2023), he put solar panels on the roof, switched off the air-con, opened the gallery to the park, and animals came in. There was an architecture of webs in the middle of the gallery, so it became the house of spiders!

I’ve always lived in small apartments, and I suppose that’s one of the reasons why I became interested in house museums, because I was fascinated with the idea that one can sort of inhabit an entire house and create a world [within it]. That was something I never did or had [before]. In 1999, Cerith Wyn Evans took me to the Sir John Soane’s Museum in London. It includes incredibly valuable things—paintings by Constable and Turner, paintings behind paintings. There’s an Egyptian mummy, but there are also branches that Soane found on his walks, so there isn’t really a hierarchy between high and low. There’s a togetherness and an extreme density of the display. And I said to Cerith that we should do a show there.

Retrace your steps: Remember Tomorrow at Sir John Soane’s Museum became the first group show I created in a house. I had already done a Gerhard Richter show at the Nietzsche-Haus in Sils Maria in 1992—another house museum—but that was a solo show. [This effort] became a series, at the Casa Barragán in Mexico, the Lorca House in Spain, and the Lina Bo Bardi Glass House in Brazil. It’s almost like the artists and I inhabited the houses and brought them back to life; Cerith would fix the record player of Barragán and play his records. Suddenly the house was alive. We brought life back into these house museums. As a curator, these houses became my temporary home, in a way, which is sort of exciting.

The reason why I’ve always been interested in rituals is that I always felt they create, not only a distance from the self but maybe a self-transcendence. It’s something [filmmaker Andrei] Tarkovsky lamented: that we are individuals afloat in an atomised society, where the loss of ritual behaviours has led to the overdependence on contingent identity. It’sinteresting that we have more and more communication and less ritual. When you have rituals, you have a community without communication—there’s an intensity of togetherness. Today you have the opposite; you have communication without community. So the collective feeling of ritual is kind of left behind. And I think in this atomised context, it’s interesting to think again about togetherness.

This idea of not really having a house and always living in tiny apartments led to the fact that I spent a lot of time in cafes. Cafes have been my home and still are. I have a lot of meetings in hotels and cafes. In Paris, I would always hang out with my friends in cafes; after dinner, we would meet at 11pm at the Café de Flore, and people from lots of different disciplines would meet there. In London, it’s a bit more complicated to do that, because the distances are so big. If you have a dinner which ends at 11pm, you wouldn’t necessarily cross the city for an hour, or 45 minutes, to get there at midnight—you’d rather go home. While in Paris, the distances are much shorter, and you just show up in a cafe, meet friends, and then go home.

Because the distances are bigger in London, one has to actually plan in advance. So, with my friends Shumon Basar and Markus Miessen, we started the Brutally Early Club in 2006— meeting at a cafe that is open at 6:30am. It’s kind of a club without a home; it’s a club which migrates and happens in these cafes which are open. The nice thing was that we could say, “Let’s do the Brutally Early Club tomorrow,” and nobody could say that they’re prior scheduled because no one has plans at 6:30am. So that was also kind of related to the home, this ritual of having weekly Brutally Early clubs.

I think that, in a way, the collaboration with LUMA Arles is about what an archive can be in the twenty-first century. Maja Hoffmann [founder and president of the LUMA Foundation] had the vision to focus on archives from the beginning; part of the Annie Leibovitz and Derek Jarman archives are held at LUMA. We started to think about how we could develop exhibitions out of my archive, because I filmed all these conversations. We wanted to begin with three protagonists who have been particularly influential in my life: Édouard Glissant, the philosopher, poet, and artist from Martinique; Etel Adnan, the poet from Beirut who lived in Paris; and last but not least, Agnès Varda, the filmmaker of the Nouvelle Vague. These three protagonists are no longer with us, but I recorded dozens of conversations with them, so it’s an attempt at creating a space where one can listen to these conversations to have a kind of living, dynamic archive.

Usually, archival works are posthumous, so it’s nice to work on an archive while one is alive and let it evolve. With Agnès Varda, for example, she moved from the film world into the visual art world after we invited her to the Venice Biennale in 2003. She said she always wanted to have a multi-screen environment, so she exhibited as part of Utopia Station with tons of potatoes, and she came to Venice disguised as a potato! We thought there was a great opportunity to have a survey of what she had done over the last 15 years until her death [in 2019]. We live in an age of a lot of information, but that doesn’t mean we have more memory; this is what the show is kind of about, dynamic memory.

I think the Instagram project is kind of the same as do it. Now in its 30th [year], do it invites artists from all over the world to write instructions for exhibitions, and it’s taken place in 169 cities. All my shows, in a sense, come out of conversations with artists— they kind of evolve, they learn, they listen, they diversify. I believe I’m a lifelong student, and I believe we always have to learn. With Instagram, it’s also about using the platform in a way that the inventors of the platform would never have thought. And then, of course, over the years [the handwritten project] evolved, it led to exquisite corpses. The project is like a living organism, in a way. But it’s also an application, like all the bigger group shows I organise, of Glissant’s ideas. He said that we have homogenised globalisation, and we need to resist that because it leads to the disappearance of our species and the disciplines of cultural phenomena. But, Glissant says, there is a counterreaction to that, which is new nationalisms and new localisms, and that’s what we can observe now all over the world, in politics and society. We have these new localisms which are intolerant.

Art needs to be a global language which is about tolerance and inclusivity, but at the same time takes into account the local. And that’s what the philosopher Bernard Stiegler tells us: We need to be local without being localist. Projects like do it or the handwritten project are, in that sense, an attempt to realise these Glissantian ideas. With the handwritten movement, it’s in many languages; when I meet somebody whose mother tongue is not English, I ask them to write in their language. I give a translation, but my followers are encountering a language they don’t understand, and they also encounter the artist [speaking this] language they don’t understand.

I’ve written books; I’ve edited books and edited catalogues and published a lot of interview books. But none of these books have ever really been personal, and I was always a bit shy [about] doing that. There’s a long tradition in France where well-known novelists “curate” series in publishing houses. And Bernard Comment, a Swiss novelist in Paris, is the “curator” of this extraordinary publishing house, Le Seuil. He’s always been convinced that I should somehow write down my life. During [the pandemic] lockdown, he rang me like an editor would who wants a book: he rang me basically every morning at 8am and said, “Have you written it?” After about two weeks into the lockdown, I thought I better start to write. Otherwise, he’s going to call me again tomorrow.

I don’t think it would have happened without the lockdown, because there was more time. I had lots of Zooms and went on walks in the park, but there were no social obligations. I would write every night to be able to tell Comment the next morning that I’d actually written something. And so that’s how this book kind of grew. It includes a chapter on my accident during my childhood, which was a near-death experience, and which really was, I think, the beginning of me somehow coming into art, because art was always a form of healing and a form of hope.

So the book has a lot to do with healing, and then, you know, it has to do with the story of my mother. She wasn’t in the art world at all, but she had this openness. When I started to travel as a teenager, to keep my parents from worrying I sent them books and postcards from everywhere in the world. Whenever I published an essay, a text, or an article in a magazine, I would send them a copy. So my mother was reading hundreds and hundreds of books and articles I sent her, because, you know, I write quite a lot, and I also contribute texts to a lot of anthologies. And she would always read the whole book.

Little by little, after 20 years, she read a lot about art. And then suddenly at 80, she became an artist, and in the last five years of her life, she made all these hidden pieces which we found in the apartment. It’s very much connected to the Italo Calvino quote you sent [for the interview], that “the fascination of the collection lies in what it reveals, as in what it conceals of the secret urge that led to its collection,” right? She made these artworks all over the apartment, which were partially hidden and partially visible.

No, I don’t think so. Collectors bring together art or whatever they have collected, and either they make their own museum or they give it to a museum. I think it’s a different activity to mine. I am a curator, and as [the Swiss curator] Harald Szeemann always said, curators have archives, not collections. I really do think that curatorial work builds up an archive and not a collection, too, in the sense that the 4,000 hours [of interview recordings] are clearly an archive; my Instagram is an archive; I don’t own a collection of artworks. It’s very much an archive that very organically grows and is driven by insatiable curiosity, which was born out of my growing up in Switzerland as a single child, feeling isolated and having an infinite appetite for knowledge and for research.

My big inspiration was the art historian Aby Warburg [founder of the Warburg Institute in London], so it came out of the idea of [having] an archive from the beginning. I write about this in the autobiography, but there was this abandoned, haunted house in a little village where my high school was, and it was this clinic where Aby Warburg was treated [by pioneering psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger] and where he wrote A Lecture on Serpent Ritual in 1923. And, of course, besides the Serpentine and Sir John Soane’s Museum, the Warburg Institute is my other favourite place. It’s a magical place, and that’s really the answer: it’s always been an archive because that’s my earliest DNA.