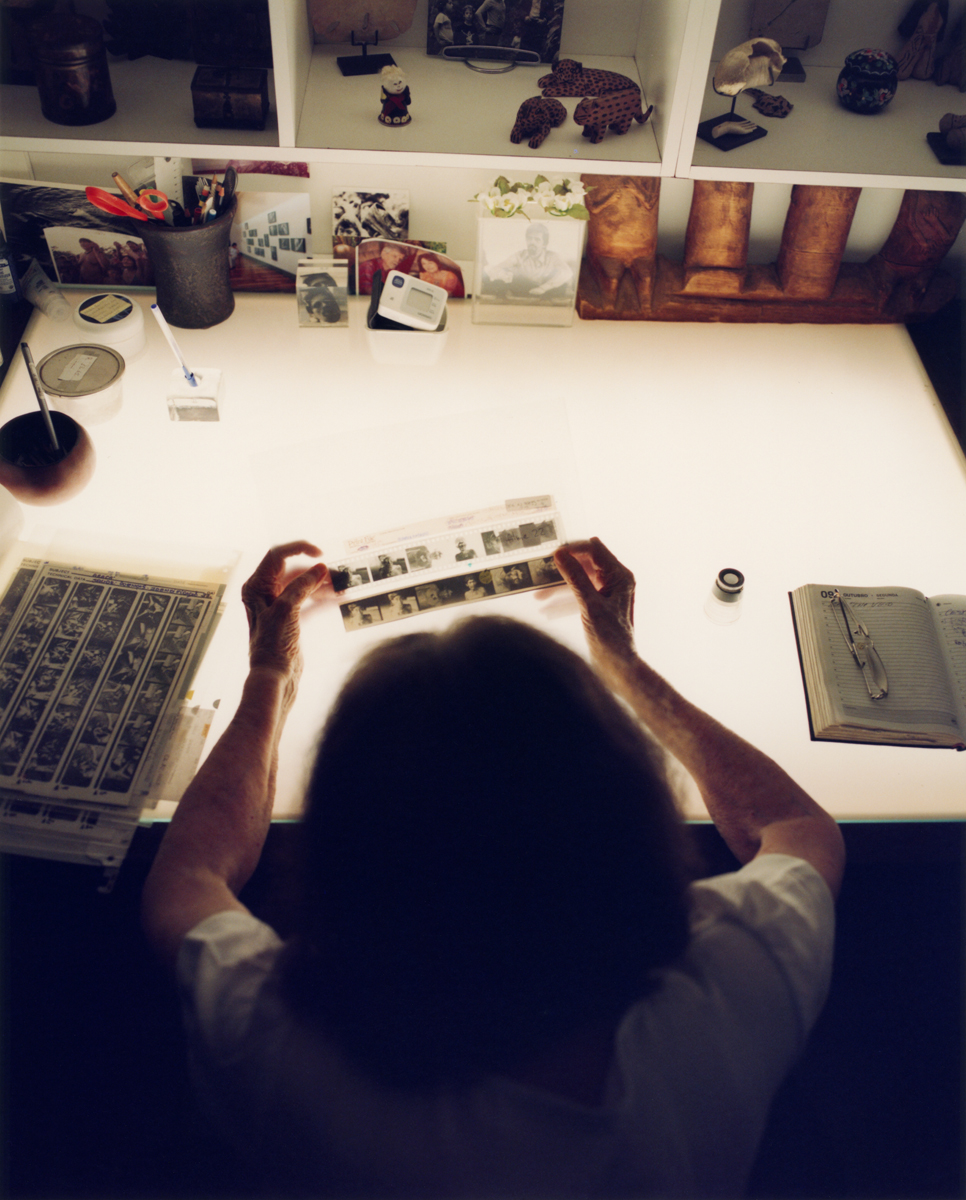

Located in a Brutalist high-rise, Claudia Andujar’s apartment overlooks São Paulo, the city that the Swiss-born photographer has lived in since 1955. On the day of Present Space’s visit, it acts as a refuge from the damp winter’s afternoon. Inside, Andujar’s home is a calming and reflective space, littered with ornaments, objects and photo books she has collected over the years. In a corner of one room, a light table is installed to allow Andujar to consult photographic negatives of her work that date back almost seven decades. Until very recently, the 92-year-old photographer would approve all images for exhibitions and publications from this desk.

Though it is São Paulo that Andujar calls home, the photographer has spent much time – months at a time, in fact – with the Yanomami in the Catrimani region of northern Brazil. Back in the early 1970s, Andujar met the Yanomami as part of an assignment when working as a photojournalist; after her first encounter with the indigenous tribe, she dedicated her life to learning about their community, livelihoods and traditions which have come under threat as a result of the destruction of the Amazon rainforest.

The connection that Andujar made with the Yanomami is a reflection of her formative years, as a child living in the throes of World War Two. Born in Switzerland in 1931, Andujar – née Claudine Haas, she would later change her name to Claudia – was raised in Transylvania (now part of Romania). In 1947, she immigrated to New York as a refugee – her father, a Hungarian Jew, had been murdered during the Holocaust alongside most of the paternal side of Andujar’s family.

It wasn’t until Andujar moved to Brazil in the mid-1950s that she began working as a photographer. As she has previously explained, taking photographs enabled Andujar to communicate with the people she encountered when she first moved to Brazil because at that time she could not speak Portuguese. Photography wasn’t just a tool for communication; it quickly became her bread and butter – travelling Brazil and surrounding countries as a photojournalist, often working on photo essays on indigenous. For a while, Andujar continued to travel back to New York, publishing stories about life in Brazil in magazines such as LIFE and Look.

These early images are typical of the humanist photography published in magazines during the middle decades of the twentieth century, focusing on everyday life as it happened on the ground as an act of universal solidarity. In 1966, Andujar began working for the magazine Realidade, where she contributed photo essays on topics in Brazilian life such as migration, drug addiction, prostitution and homosexuality. The magazine had been launched the same year that Andujar was employed there and focused on in-depth stories on Brazilian life from a new journalism perspective and as a riposte to the military regime that had been installed in 1964.

Though press censorship was imposed by the regime in 1968, this would not deter Andujar from covering what would become the defining story of her career at Realidade. In 1970, she began work on an investigation into the impact of the construction of the Trans-Amazonian highway in the north of Brazil. As part of this assignment, she was introduced, through anthropologists and missionaries, to the Yanomami living in Catrimani. While the proposed story for Realidade intended to focus on the impact of the highway’s construction (in order not to provoke a backlash from the military regime), Andujar persuaded the magazine to publish photographs that she had taken of the Yanomami themselves.

Published in 1971, the photo essay, titled Amazônia, both attracted the ire of the military regime (by 1976, Realidade had been shut down) and led Andujar to quit her job as a photojournalist. That initial encounter with the Yanomami inspired her to spend her time getting to better understand and connect with the community. Andujar returned to Catrimani soon after, beginning many of the back-and-forth trips from São Paulo that she would conduct throughout much of the 1970s.

At first, Andujar did not take her camera with her, hoping to gain the trust of the Yanomami. For one, the Yanomami tradition holds that all objects and depictions of individuals should be destroyed upon death so that their spirits can travel on to the next world. Over time, Andujar was permitted to photograph the community and their customs – a reflection of her efforts to campaign for, and alongside, the Yanomami.

Just as photography had been a way for Andujar to communicate with the people she met in Brazil twenty years prior, it now became a way to connect with the Yanomami on their terms. By employing a series of techniques, such as reducing the camera shutter speed, using multiple exposures and creating blurs by smearing Vaseline on the lens, her photographs from this period demonstrate how Andujar sought to capture a sense of how the Yanomami saw their world through their eyes. Lens flares and artful blurring create ethereal images of the Yanomami’s everyday life and rituals with a dreamlike vividness. In doing so, Andujar eschewed the photojournalist gaze of her earlier assignments to celebrate and emphasise a world unfamiliar to her own.

Andujar’s practice would shift once more in the late 1970s, as the threat to the Yanomami’s existence came under renewed pressure. Brazil’s military dictatorship had embarked upon commissioning a second major highway through the Amazon, as well as allowing the mining of the rainforest of its resources, through logging, cattle ranching and gold mining. Andujar, meanwhile, had been banned from the Catrimani region in 1977, seen as a dangerous and outspoken critic of the government’s policies.

As a result of the military regime’s destructive pursuits in the Amazon, infectious and deadly diseases were introduced to the Yanomami at alarming rates, brought in via the influx of construction workers, loggers, and gold miners to the region. In response, Andujar pivoted her attention to activism, and in 1978 helped to cofound the CCPY (Pro-Yanomami Commission), a non-profit campaigning for the demarcation of Yanomami land. Though she continued to photograph the Yanomami, her camera became a tool to assist the work of the CCPY.

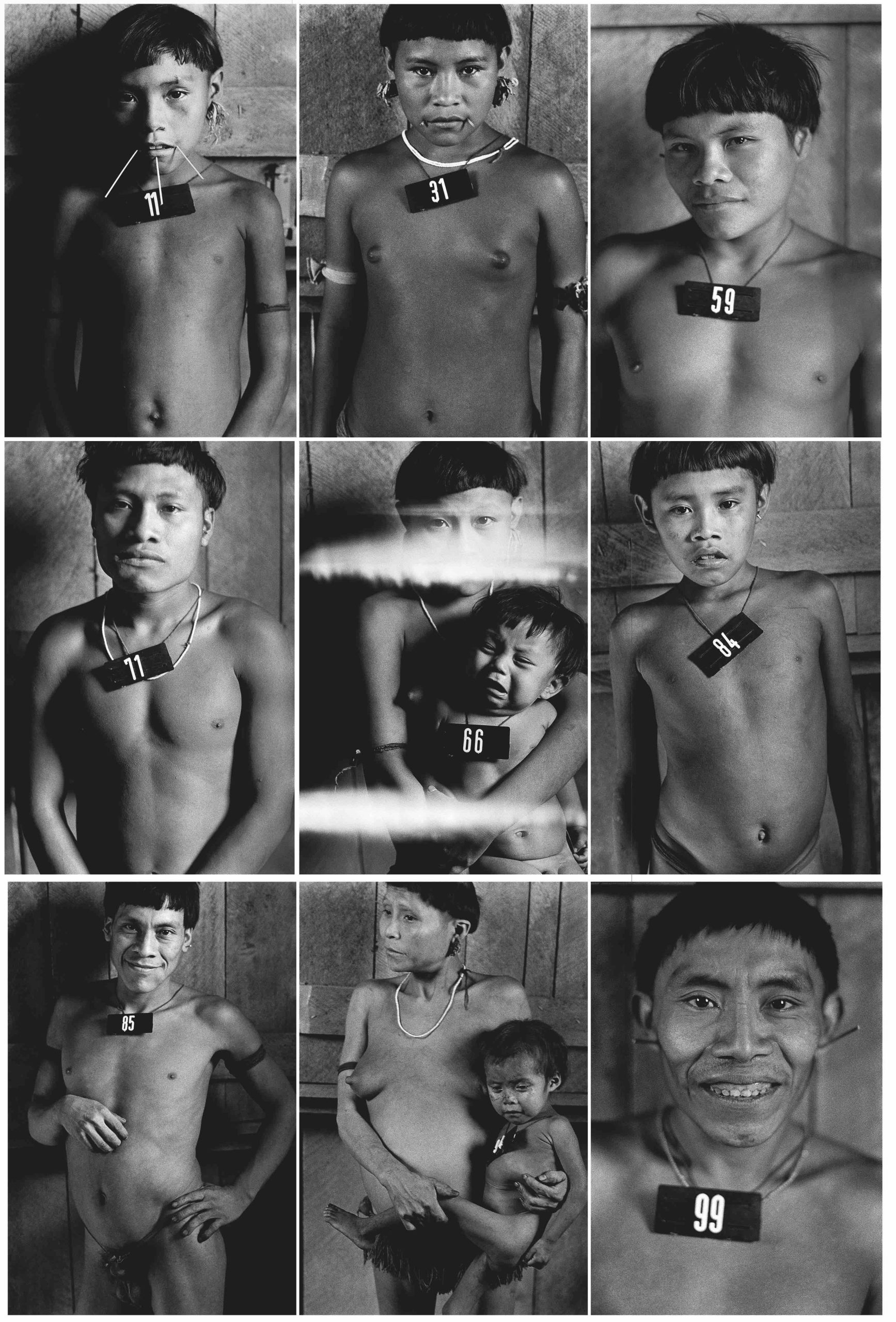

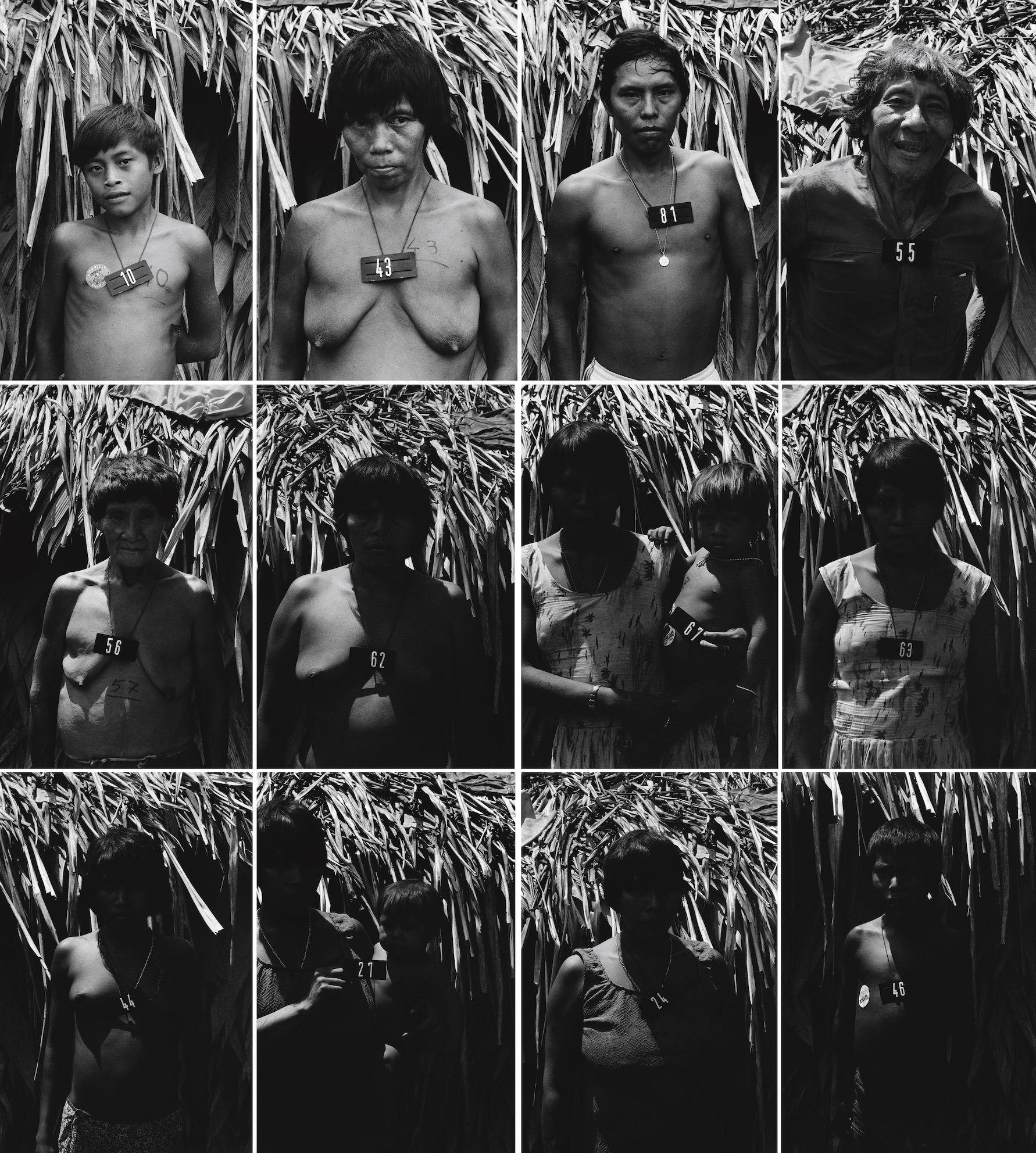

In the early 1980s, for example, Andujar worked with the CCPY and medical specialists as part of a vaccination campaign against the spreading of diseases throughout Yanomami communities. To establish and keep track of the medical records of the Yanomami (who, for the most part, did not have Portuguese names), medical specialists designated each person with an individual number tag; a process which Andujar documented with her camera.

Andujar would later revisit the photographs that were taken as part of these vaccination efforts, compiling the images into the Marcados series for the 2006 São Paulo Biennial. She compared the use of number tags to the tattooing of those sent to concentration camps during the Holocaust, emphasising a reverse experience between the persecution of her own family, with the efforts to protect the Yanomami, despite the military regime’s destruction of the Amazon and its peoples.

In doing so, Marcados is an example of how Andujar has long since used her photographic archive to continue raising awareness of the Yanomami’s ongoing plight in the face of government inaction towards the mining of the environment’s resources. Later, in 2018, Thyago Nogueira curated Claudia Andujar: The Yanomami Struggle, an exhibition at the Instituto Moreira Salles that followed several years of archival research into Andujar’s work, focusing on her involvement with the Yanomami over five decades.

After being staged at the IMS’s galleries in both São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro in 2018 and 2019, respectively, the exhibition was brought to the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris. It has since been staged at other locations including the Barbican Curve Gallery in London in 2021, and most recently, in 2023, at the SHED in New York and the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City.

The travelling nature of this exhibition recalls Andujar’s activism throughout the 1980s and 1990s with the CCPY and Davi Kopenawa, a shaman and spokesperson for the Yanomami. After travelling the world to raise awareness of the Yanomami’s plight with the CCPY and Kopenawa, their campaign successfully pressured the Brazilian government into recognising the demarcation of Yanomami territory in 1992.

Yet, time has shown that the work of the activist is never done. Shortly after the opening of The Yanomami Struggle at its first location in São Paulo, Jair Bolsonaro was elected as Brazil’s far-right president who, during his tenure, reopened the Amazon to illegal gold mining. While the election of the left-wing candidate Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in early 2023, is an indication that things might change, Bolsonaro’s presidency demonstrates that the task of fighting for universal human rights is never over.

For example, in late 2023, after the opening of an exhibition of Andujar’s work, titled Yanomami. Spirits. Survivors. at the Museum of Ethnography in Budapest, part of the show was fenced off from viewers under 18. The images cordoned off from the exhibition are from a 1967 photo essay Andujar contributed to Realidade on homosexuality in Brazil under the military regime; the inclusion of such images was deemed a contravention of a 2021 law enacted by the populist rightwing government in Hungary that prohibits the dissemination of LGBTQ+ content to minors.

In her São Paulo apartment, Andujar has kept many of the objects that she had been gifted by the Yanomami over the years. While she is no longer able to make journeys to the Catrimani region on account of her age, The Yanomami Struggle can be seen as a continuation of Andujar’s commitment to working with the Yanomami. Just as the photographer has sought to do throughout her work, the exhibition is designed to highlight the Yanomami way of life from an insider’s perspective. To that end, the exhibition includes artworks, drawings and films made by Yanomami artists, including Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe who exhibited at the 2022 Venice Biennale.

Writing in Yanomami, a 1998 monograph on her photographs from the 1970s, Andujar noted that her work ‘has still not found its definitive form, which I believe does not exist. Like myths, it adapts, incorporates new images, and assumes new forms […] in an infinite virtual bricolage.’ As Andujar shows Present Space some of the negatives that she has acquired over the years, what is clear is that hers has been a life spent trying to understand, and connect with, the lives of others – possibly the most human trait of all.

Claudia Andjuar’s exhibition The end of the world, opens on February 9th, 2024, running through August 11th, at the Deichtorhallen, in Hamburg