I meet D Harding at the Lisson Gallery in West London in early May, where the artist is preparing for the opening of the Matter as Actor group show later that evening. Harding, has spent the last two weeks in London ahead of the exhibition, having flown over from Brisbane, where they live and work (Harding is a descendant of the Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal people who come from the land that is today known as Central Queensland). Matter as Actor, which draws upon the work of artists investigating the notion of matter as an active embodiment of the complexities of human existence, is a show that is well-positioned to unpick the complexities of Harding’s own practice.

Harding uses a range of mediums (in the case of Matter as Actor, the focus here is on different pigments that they have used in previous shows) to examine space and place through an historical, cultural and spiritual lens – using materials and processes to navigate and untangle processes of colonisation, globalisation and the exchange of goods as well as ideas. Many of the processes that Harding employs as an artist have been learned from family members; likewise, Harding often uses materials that are safely sourced from the cultural landscape of the artist’s ancestors. Exhibiting cultural processes in an art space, Harding’s work adds a further level of complexity to their practice: “there’s an Aboriginal cultural way to speak around the whole show, and there’s [also] a more global or more international conversation around contemporary art history.”

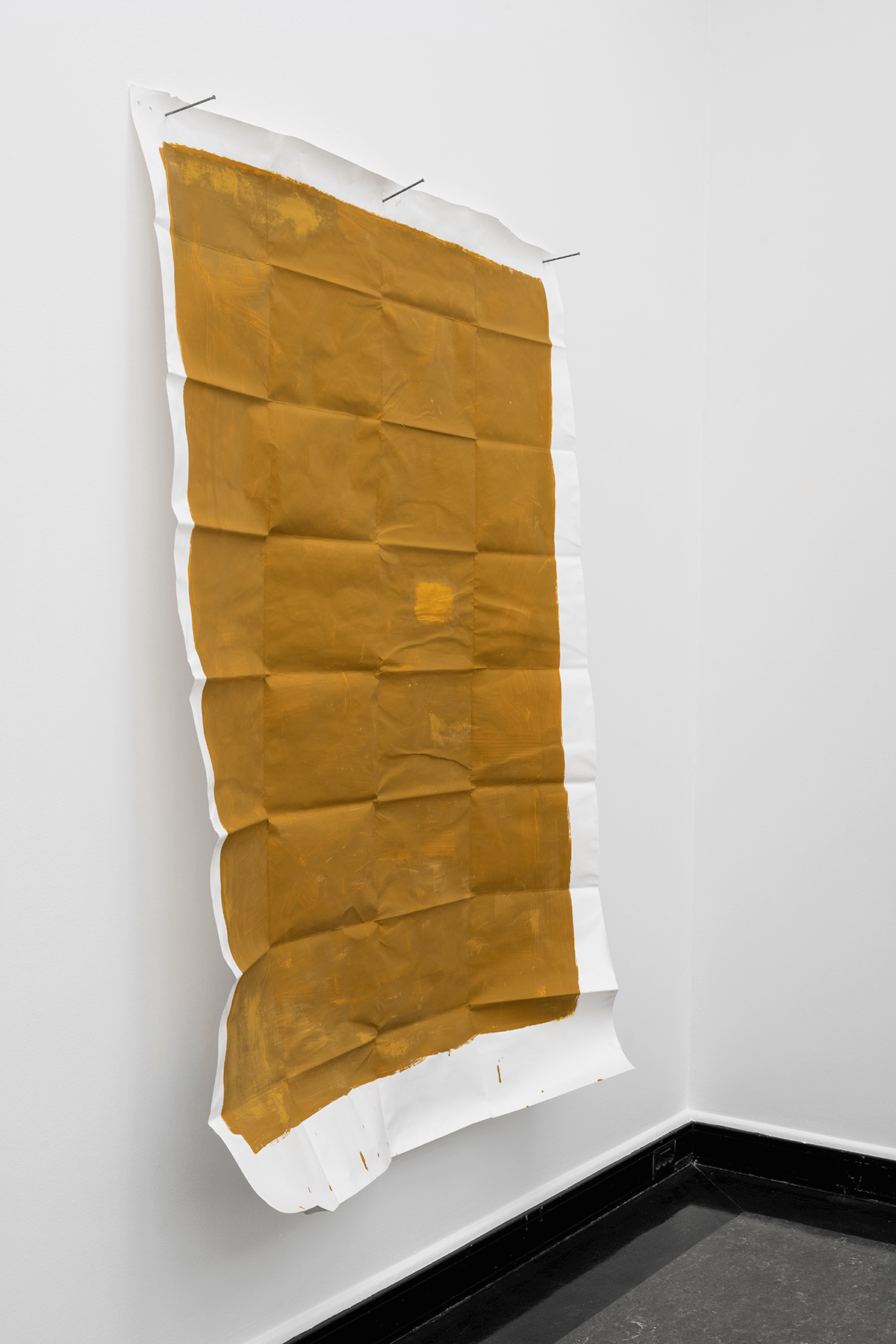

For the show, Harding has created two new works, I have learned your history, as well as my own and She come from the low-country, he come from the high-country (both 2023). Also on display at the Lisson Gallery is one of ten sheets from the series As I remember it, which was first exhibited at the Bergen Kunsthall in Norway last year. As part of that work, the artist covered each sheet with a thick layer of yellow pigment mixed with gum Arabic.

By rewetting the pigment on the sheet, Harding has also created a direct intervention in the Lisson Gallery space, painting the gallery’s skylights. As for the pigment used, it was bought by Harding in Sweden in 2018. Explaining the journey that this yellow pigment has been on, the artist notes that, after purchasing and using it in Sweden for an exhibition, “it went back to Brisbane. Late last year, I decided to make these yellow works for the show in Bergen, and then it’s [returned] to Brisbane, and then come back here again. And that’s all quite deliberate.” As I remember it thus considers the boundaries of art and resource; though the sheets are hung on the wall in the manner of an artwork, each one can be folded and neatly packaged down – to be transformed across the globe, and used as again for another artistic intervention.

Central to Harding’s practice, then, is a recurring exploration of exchange and movement. In part, this is negotiated through the artist’s own journeys into gallery spaces and the places in which they are located. For instance, that yellow pigment purchased in Sweden stemmed from its visual similarities with the yellow lichen that grows on roofs and rocks especially in areas by the sea, like Stockholm. In that way, the yellow pigment was a means for Harding to honour a local story and context. For an upcoming exhibition at the TarraWarra Museum of Art this summer, Harding will create window paintings by working with a local Aboriginal family who will collect pigments from their community. In this way, Harding is not bringing materials in from outside, while the family can “enjoy the process of locating and learning about the pigments of their territory.”

Other materials that Harding has used have also allowed the artist to directly consider the impact of exchange and oppression in Australia. In previous works such as Wall Composition in Bimbard and Reckitt’s Blue (2018), the artist used a powdered laundry brightener (“Reckitt’s blue”) which was first manufactured in the mid-nineteenth century and popularised in Australia’s colonial frontier by the end of that century. At first sight, this vivid ultramarine pigment recalls the Modern art world of Klein blue, yet for Harding it evokes a different kind of art production.

As Harding explains of the Reckitt’s blue, “Aboriginal people have a very long experience of working with powdered dry pigments in ochre and clays. When the colonial frontier arrived with these prepackaged little parcels of blue dry powder pigment in an ultramarine that had never been seen in that intensity, the way I look at it is that [Aboriginal] people already knew how to handle that material.” Yet, though the Reckitt’s blue evokes the exchange of resources and cultural practices, it was not an equal trade – the powdered detergent also has associations with the Aboriginal women working in domestic service throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and is, as such, “tied up in the abuse of women and the systems of government oppression, legislated oppression of Aboriginal people.”

The synthetic pigments that Harding uses, because they are manufactured industrially, are uniform materials with no impurities. Meanwhile, clays and ochre that come from Harding’s ancestral landscape, though often pure and fine, exhibit specific characteristics that connect them to the place that they are from. As Harding explains, family members can often identify where a pigment came from by touch and sight, and can tell “who that [land] belongs to ancestrally, who the family, the kinships and the relations are that still live around that location”. Some family members can go as far as recalling taste profiles too. “One of the colours in a similar region [to Central Queensland] is described as being like McDonald’s soft serve in the mouth, because it’s super creamy and super soft and it’s almost slightly sweet.”

For I have learned your history, as well as my own on display at the Lisson Gallery, Harding combines another synthetic pigment (crushed PrEP antiretroviral tablets) with a different ultramarine blue. This blue, however, does not have industrial and colonial connotations, but relates to the mining of the earth’s natural resources. Harding uses a hand-milled lapis lazuli, which is sprayed onto stretched linen using an atomiser. As a semi-precious stone, lapis has been mined in Central Asia for millenia, on account of its rich, deep blue colour; its usage as an art pigment in European art history, meanwhile, dates back to the Renaissance.

Used by the artist at the Lisson Gallery, in which the lapis lazuli is almost in conversation with the pigments collected from Harding’s grandmother’s country (Ghungalu) and grandfather’s country (Bidjara) in She come from the low-country, he come from the high-country, the notion of exchange and movement takes on a different meaning. As Harding remarks of the spray marks on the linen, “this body atomised that tube, an Aboriginal body, atomising a pigment that’s come from global and particularly European art history.”

One of the things that is really necessary, particularly presenting ourselves in both an Australian local context, but also internationally as Aboriginal people, is to be so precise in language and description – because a lot of my intention is to write into the record. So it’s crucial for me to identify the specific language group, and that is, for example, Garingbal white ochre, which [people from that community will know] specifically where that is [from] and the whole story around it. In the same way, identifying the store-bought pigment is just as important because I’m trying to catch [out] lazy assumptions.

I work to encourage [family members] to think about art spaces in the same way that our bodies and our family are familiar with being in the ancestral sites in the landscape. It took me a while to get to this point, but two colleagues in Brisbane [Merindah Donnelly and Warraba Weatherall], two Aboriginal people in the arts, helped me understand that I was looking at the white cube, or the museum space, through an Aboriginal lens. And so, my family can walk into a space, if I can encourage them to feel safe, if we all can encourage them to know that their cultural knowledge is important here.

It’s a constant negotiation for me personally, and with the colleagues that I’m working with. We probably all agree that, historically and still [to this day], there are many barriers that make museum spaces and contemporary art spaces unsafe for all sorts of different communities and people. Do I think the gallery is a safe third space? We’re getting there. I’m only one practitioner, but I understand that lots of other conversations are still drawing attention to the clear boundaries and barriers and processes which makes people unsafe.

One of the things that I really try to do is to familiarise my family with these places. As Bidjara, Ghungalu or Garingbal people in Central Queensland, [we don’t] have many chances to practise and live our cultural inheritance in the landscape. And that’s largely why I came to work in the museum space – so we can be doing it for ourselves and for each other. Through that, my family have developed more of a sense of safety and deep familiarity with contemporary art galleries. One of the ways of [creating safety] is to recognise that, even though there’s lots of cultural knowledge in here, it’s also quite distinct from what you might find in the landscape. It is contemporary art. We’re still present as contemporary people, and our inheritance is still here.

I started off wanting to be involved in cultural making as a young person and I took up making paintings that might be considered “tourist art” (we weren’t selling to tourists, but it had that kind of format). We were making them for ourselves, not even to be exhibited, but we were drawing on some of those tourist art conventions. Some of the ways of making that I’ve brought into museums I will no longer do. Spectatorship – that belongs to us, and some of those forms, like spraying ochre on the wall using my mouth, is not something that I’ll do readily anymore. We’ve had more opportunities [in the gallery setting] and now, more family members have [learned the] skill in being able to work with [certain] materials and embody [cultural] processes, and so then that belongs to us again. I’ve needed to shift and recalibrate what I might present, again looking at safety, constantly asking questions about what I might be exposing or revealing.

I learned the semantic distinction between “re-” and “de-” prefixes when I was doing my postgraduate research. And “re-” and “de-” words, in terms of the First Nations context in Australia, were really crucial – like revival, reawakening, decolonising. But someone pointed towards the fact that re- and de- we’re still prioritising a position we don’t want to be in. So, to decolonise is to prioritise the colonised position. So I’ve completely wiped them out of my head now. Our family now has the approach that [the land] was taken from us. Or, it’s the first time that I’m getting to [use cultural ways of making]. In terms of the making, the knowledge bases are still enough intact that it’s just our first time: we’re just doing it now.