Back in 2020, siblings Imre and Marne van Opstal decided to embark on a full-time creative partnership as choreographers. As professional dancers, the pair had danced with renowned companies, including the Nederlands Dans Theater (NDT) 1 and 2, where they grew up. Speaking over Zoom, Imre and Marne explain that the decision to work together as choreographers was something of a natural process; they learned to dance as kids alongside their siblings Myrthe and Xanthe, who were also professional dancers with Nederlands Dans Theater and the prestigious Batsheva Dance Company in Israel (where Imre previously danced, too). Besides the small dances that they conceived together as kids – at home or for school projects – Imre and Marne’s first collaboration was The Grey from 2017 for NDT 2.

Since then, they have choreographed a number of works in quick succession, from Baby Don’t Hurt Me and Eye Candy (both 2021), to The Little Man and Heart Drive (both 2022). Recent works also include I’m Afraid to Forget Your Smile (2022) and To Kingdom Come (2023). In different ways, each of these works explores aspects of the human life, from an exploration of identity, sexuality and gender in Baby Don’t Hurt Me, to an attempt to grapple with the physical and emotional constraints of the human condition in works like The Little Man (there’s an existentialism to their work, Marne explains over Zoom). These themes are explored through a dynamism in their choreography that is also often reflected in the visual presentation of their work; Eye Candy, for example, dancers clad in silicone breast plates give the illusion of nudity – as a comment by Imre and Marne on the hypersexualisation of the human body.

Besides working on these joint projects, Imre and Marne have collaborated with the likes of musician, Lykke Li, choreographing dancers for a section of the visual accompaniment to her 2022 album, Eyeye. They also worked with Maria Grazia Chiuri for the Dior S/S22 show last September, to envision a performance that paid homage to the collection’s Renaissance influences.

At the time of our call, Imre and Marne have recently arrived in Helsinki, where they are working with the Tero Saarinen Company to re-stage Heart Drive this June, which was first performed with the Ballet BC company in Vancouver last October. Though they have only been choreographing full time for three years, Imre and Marne are in full demand – with an upcoming project between the NDT 1 and Studio Drift (an artist collaboration based in Amsterdam) also in the works. This level of high intensity is not something that seems to phase either sibling though – while they acknowledge it’s not an easy lifestyle, it’s one that also comes instinctively to the pair.

I think for us, [the shift from dancing to choreography full time] felt intuitive because we started creating while we were still dancing. So we didn’t have to [just] quit everything. It’s incredibly exposing; you really put yourself on the line. It can be very scary. [But as choreographers] we put our emphasis on our curiosity to create because I think that’s, in the end, why we do it. And I think what’s really important for us is connecting with people in the first place: with ourselves, with our creative partners, with the dancers in the studio, and then with the audience.

Marne and I, we both came to a point in our careers [where we had been able to] work with all the great choreographers that we wanted to work with, we got to practise different styles, we got to see how other choreographers work. And I think we came to the conclusion that we wanted to create our own voices and develop something together.

As a dancer, you’re quite shielded from everything that choreographers go through; there’s so much that happens behind the scenes that you are protected from as a dancer so that you can do your job efficiently. But as a choreographer, you’re planning way ahead. You have to come up with concepts and ideas. You have to create a whole world. There’s a whole process that you go through before you even set foot in the studio. [That said], I think they’re intrinsically linked – we’re using what we learned as dancers in what we do now.

Dancing is a deep, personal emotional process for many people. I think as a choreographer, you really need to respect that. But that’s also the beauty of it. Through the body, we learn from each other. We actually speak with the body, without words (of course, we use words in the studio!) But I think it’s more about how we can channel all of the things we want to get rid of, all the things we want to gain from the body. In that way, dance is a very powerful medium.

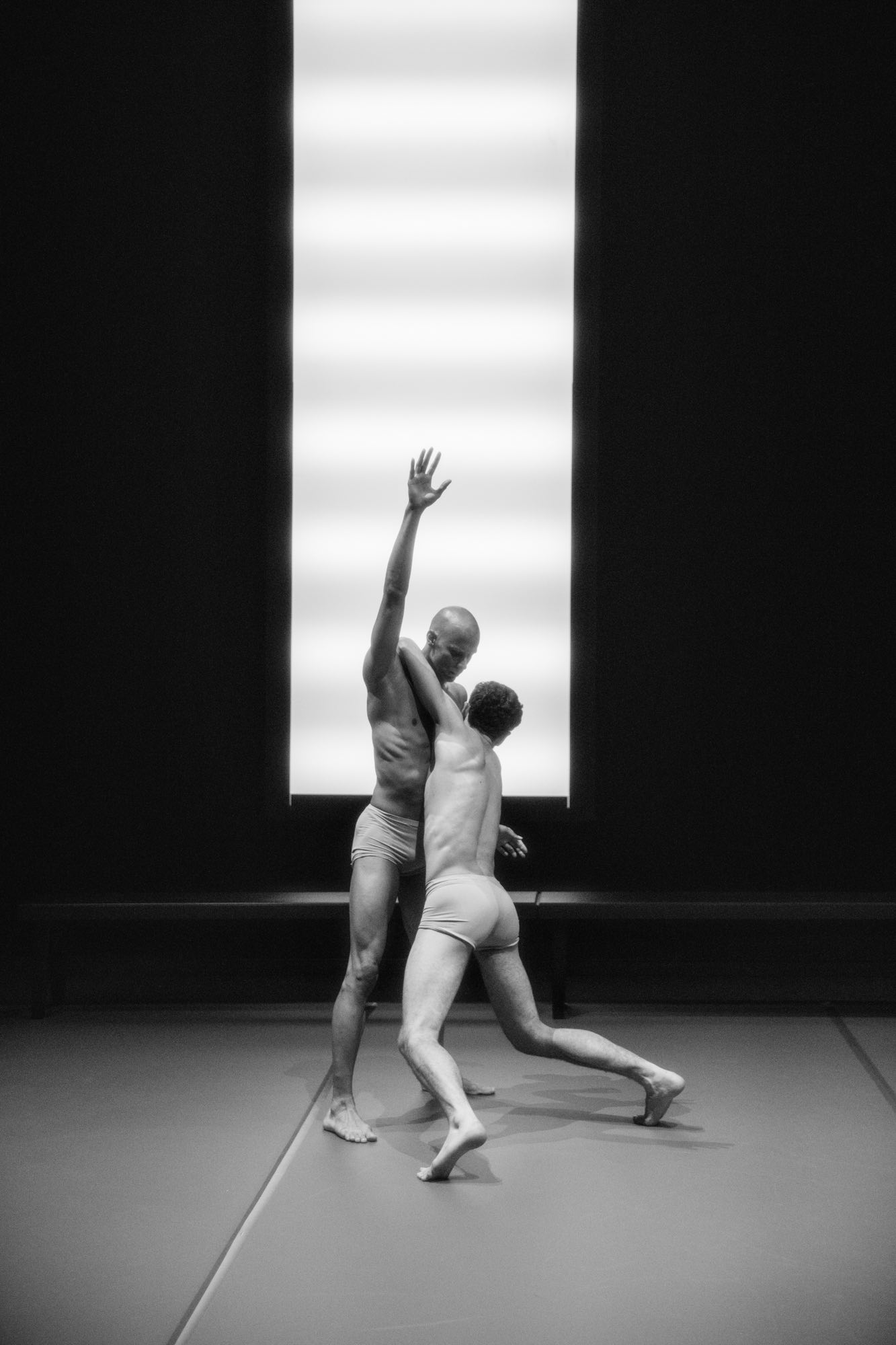

Dance is form. You’re sculpting the body. You’re creating form through motion. Whether it’s through form or through the actual spacing of the dancers, or through the way you use the relationship or the space between two people, you’re constantly thinking about what space and form is creating in time. That’s what you’re constantly playing with, and you can’t quite explain it. You just know it when it works, when it feels right, and when it’s touching you to some degree.

Or even when it’s when it feels uncomfortable. We don’t just create to make beautiful things. We also [want to] challenge people. And I think this is the most important thing that gets forgotten – that everything needs to be beautiful all the time. Sometimes we need to show what’s wrong about something and to oppose something in that, or to create friction.

It’s funny, we never realised that this is a thing that we do. It’s not that we’re unconscious of it [but] it doesn’t feel like it’s what we’re trying to do. With Eye Candy, which we produced with Rambert Dance Company, we had the dancers wearing silicone breast plates – maybe that was a little bit more in your face, like you say.

But I think it was more in your face in that sense that we wanted to show what was wrong with the human body as a taboo. Why can’t we show the body as the human form that we possess? I think by using the silicone, we were actually saying this is what we live with: this is our shape and our form.

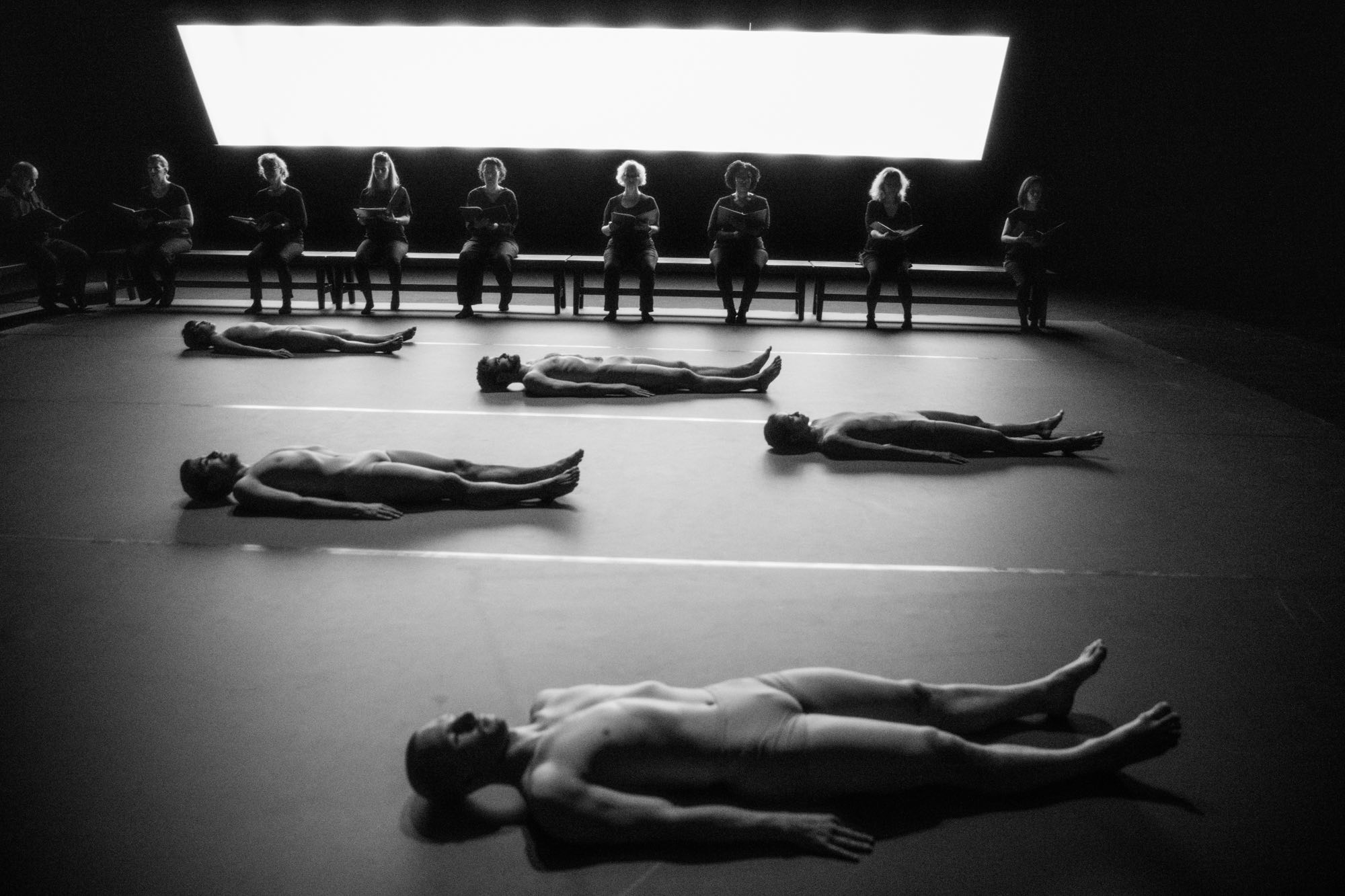

We’re always reflecting on the world, and we do this in collaboration and in dialogue with each other. What Imre mentioned earlier, we find friction points or things that we want to explore, and we go into the studio and dive into that with the dancers, to see what emerges from working with that group of people.

Which is also in close dialogue with them, because all of these people that are standing in front of you, they have their own life stories, their own trauma, their own life experiences. For us to create something with them, we want them to be on board with us. So the dialogue is very open and we want to create a vulnerable place for them to be honest and share what they can.

There’s an honesty that we always think is super important to have in the work, but also in the experience for the dancers. It is live. You’re experiencing things as they are happening [during a performance]. I think the way we work is very much centred around this idea of being able to feel the performance.

No show is ever the same. And that’s so different to other art forms [for example] as a director, after you’ve shot a film and made the final cut, that film will never change. Dance is constantly in flux, sometimes frustratingly so. That’s also why we sometimes like to work with film, to have something that [is permanent], to work with a different lens and tell stories from a different perspective.

It’s not an easy medium [to work with], purely because cameras move and dancers move. You need to leave space for both to exist. So you have to be very sensitive with what you do with the camera; when to move and when not to move.

The camera is your partner, so you need to choreograph the camera for it to work.

Through film you can also create a very different story. You can jump from one thing to the other thing. [Whereas], in the theatre, you have to direct the audience’s focus with lights [and set design] because you see the whole stage.

These are two different mediums: it’s the fashion and the models, and then it’s the choreography and the dance. [You have to create] space for the clothes to be seen because people want to see the clothes, right? People don’t necessarily come to a Dior show to see dancers! So you need to be sensitive in creating space for everything to exist.

[Fashion shows] are a well-oiled machine. We’re so used to doing everything ourselves, but you walk on set there and everyone has a job and there’s so much to be done. It’s pretty incredible. But again, it’s a very different process. The commercial world works very differently to the dance world. But we love to cross over into these mediums, because we think there are so many points where they actually converge; where dance really does meet fashion, film, music or installation art. There’s so many things that you can work with – so we think, “yeah, why not?”