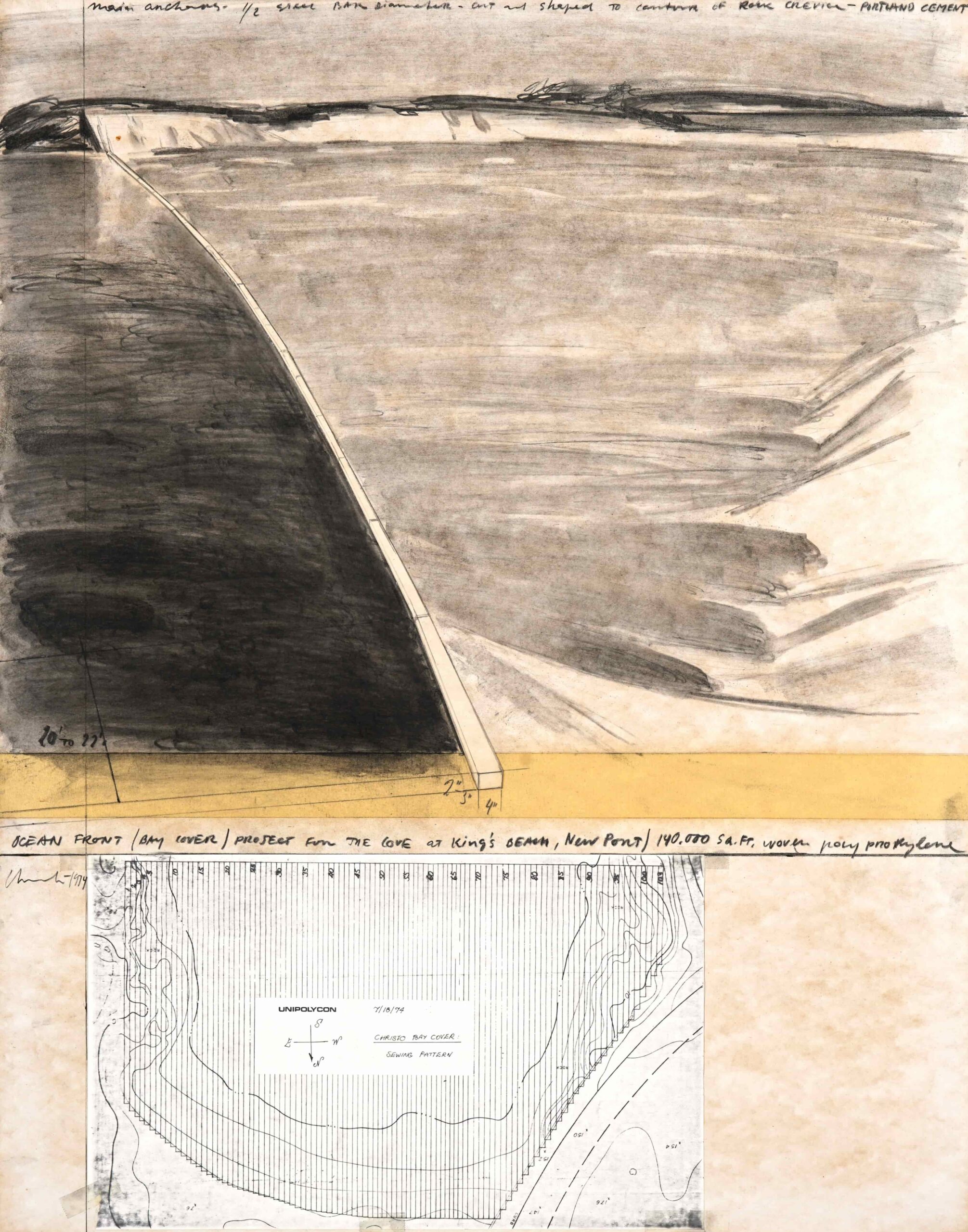

For eighteen days in the late summer of 1974, the rocky cove of a beachfront in Newport, Rhode Island, was covered with white material, creating a shimmery mirage where the thick, woven fabric buoyed against the water’s surface. Like a gliding swan, however, the events at King’s Beach were not so simple. Rather, it was a meticulously orchestrated temporary art installation undertaken by the artist duo, Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Conceived as part of Monumenta: Sculpture in Environment, an open-air exhibition held in Newport between August and October of ’74, Ocean Front is evocative of much of the artists’ work. With 150,000 square ft of white polypropylene required for the installation, the material was laced along a large wooden boom, the length of the seafront and anchored at twelve points.

At Newport Art Museum this summer and autumn, an exhibition celebrates fifty years since Ocean Front, showcasing the extensive preparation undertaken by Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Detailed illustrations and collages show how the project was set to unfold—from anchor specifications to general impressions of how the work would look once installed. This archival material underscores the artistic and technical ideas underpinning the artists’ approach to their work. As the critic and friend of the artists, Jill Spalding, wrote in Studio International in an interview with Christo in 2018, “Scale in [their] vocabulary is as much an aesthetic as a mathematical device”.

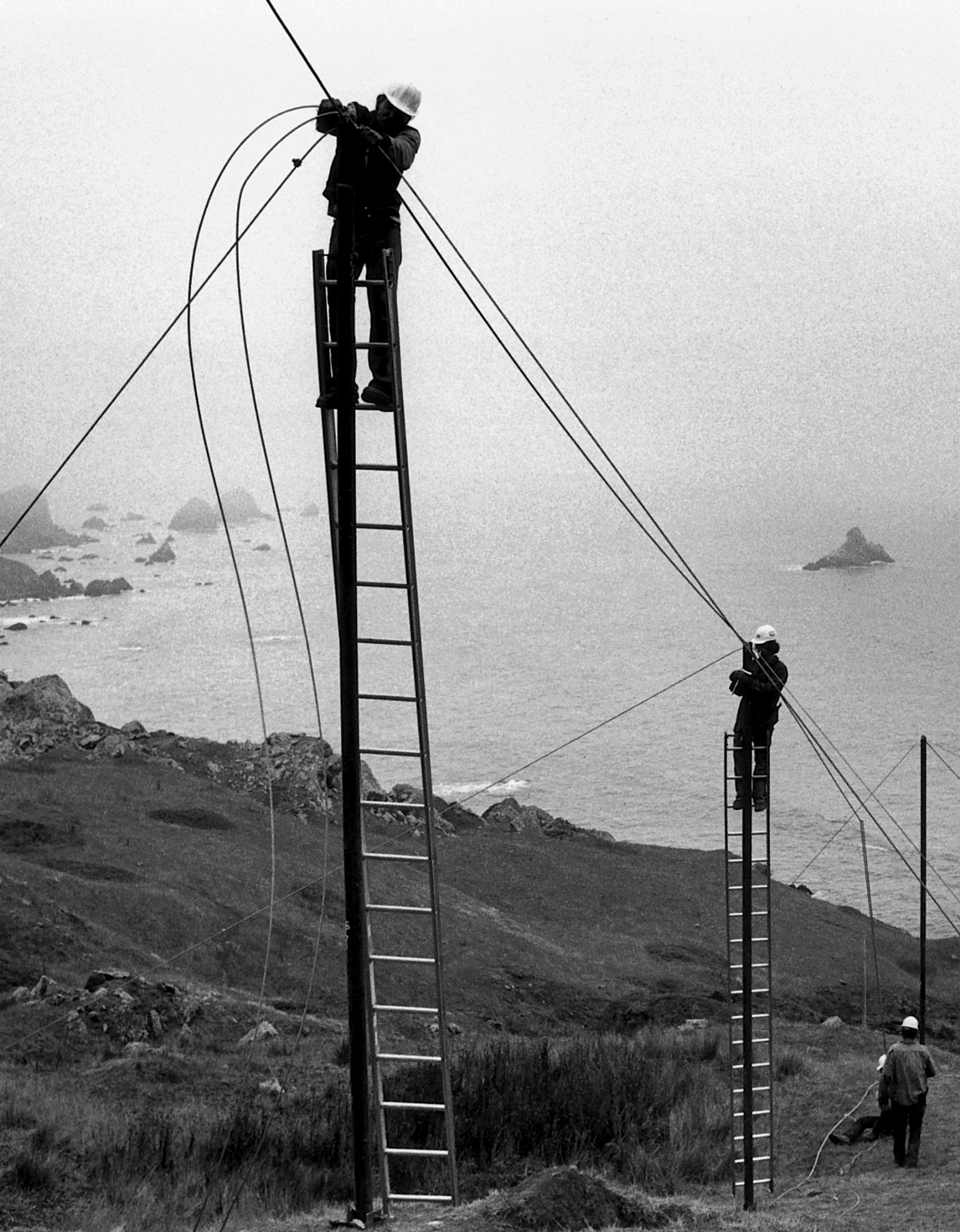

Having met in Paris in 1958—Christo had moved to Paris that year, working as a society portrait painter and was commissioned to paint Jeanne Claude’s family—the pair quickly became close collaborators, in a partnership that would last over five decades. Early artworks made by Christo at the beginning of the 1960s reflect the domestic life of a young couple; while Christo began with pieces like Package (1960) that alluded to the possibility of an object beneath fabric wrapped in rope, he soon turned to wrapped objects taken from their everyday life, such as Wrapped Telephone (1962) or Package on Baby Carriage (1962), in which the seat of their infant son’s pushchair was concealed with pink polyethylene, tied with rope. The limits of what could be wrapped would soon reach far beyond the domestic scale. Even Ocean Front was, if anything, small-scale in comparison to other projects by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, as the name of their 1968–69 installation, Wrapped Coast, One Million Square Feet, suggests. For ten weeks in late 1969, the coastline of Little Bay in New South Wales, Australia, was wrapped in a synthetic woven material, affixed using 35 miles of polypropylene rope. As with Ocean Front, there is something otherworldly about looking at photographs of Wrapped Coast. From afar, the material seems to hang and billow from the rocks like a soft, lightweight cotton, but the rigidity of the shiny synthetic fabric becomes apparent when it appears in the foreground of photographs.

It took 15 professional mountain climbers and over 100 people—including architecture students, artists and teachers—to complete Wrapped Coast. In one photograph, two figures can be seen standing atop of the rockface, just possible to make out and reinforcing the sheer scale of the temporary installation. It’s an image that recalls a preparatory collage made by Christo in 1968, in which a small cutout figure in the bottom left corner stands, his head tilted slightly as he looks on at a small section of the 15-mile long wrapped shoreline.

While wrapped projects such as Wrapped Coast evoke the sublime, Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s attentions were also concerned with wrapping cultural landmarks, starting, for example with Wrapped Kunsthalle (1967–68) in Bern, Switzerland, in which the exterior of the building was shrouded in polyethylene. But even this could be improved and expanded upon and was soon followed by Wrapped Museum of Contemporary Art (1968–69), for which the artists wrapped the exterior of the MCA in Chicago in dark brown tarpaulin and wrapped the interior of the lower gallery. What is an art gallery without the art? In 1970, the critic David Bourdon aptly referred to Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work as “revelation through concealment”. By wrapping spaces and places that are recognisable of the urban environment, the artists would draw attention to the fact that we sometimes fail to recognise that presence. In the early ’70s, they began to draw up schemes for wrapping ever larger cultural monuments: there was Wrapped Reichstag (1971–95), Wrapped Roman Wall (1973–74) and The Pont Neuf Wrapped (1975–85). The latter, covered in 450,000 square ft of a sand-coloured woven polyamide, was reduced to a silky mirage—the textures and surface details of Paris’s oldest bridge smoothed over. As the art critic Lawrence Alloway once observed, these wrapped works demonstrate “an exploration of the geometry of surfaces; as the covering stretched from point to point of the enclosed object or objects, the connection made new forms as they spanned the area.” Turned into an artwork, the Pont Neuf also became an object.

Objects themselves are capable of gaining cultural significance: as Roland Barthes wrote in 1957, “I think that cars today are almost the exact equivalent of the great Gothic cathedrals: I mean the supreme creation of an era, conceived with passion by unknown artists, and consumed in image if not in usage by a whole population which appropriates them as a purely magical object.” While Barthes was writing about the Citroën DS 19, the artists would turn to another recognisable model, the Volkswagen Beetle, wrapped to coincide with a solo exhibition of Christo’s work at the Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf. In black and white photographs of Wrapped Car (Volkswagen) (1963), Christo and Jeanne-Claude can be seen wrapping a ’61 Beetle, identifiable by its concealed silhouette.

Given the temporary nature of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work, installations like Wrapped Car exist largely in the archive, in which bodies of vast work are recorded in photographs, collages and drawings. This does, however, lend itself to recreating past projects, as Christo did when visiting Düsseldorf fifty years after Wrapped Car (Volkswagen) was first realised. Working with his nephew, Vladimir Yavachev, Christo revisited this work with Wrapped 1961 Volkswagen Beetle Saloon (1963–2014), wrapping a ’61 model in the same mint green as the original car in a thick, waxy mustard cotton. As Yavachev recalled “[Christo] really loved the way…the Beetle was imprinted on the fabric, especially with the wax and everything else.”

While the original Wrapped Car was only ever temporary, Christo intended Wrapped 1961 Volkswagen Beetle Saloon (1963–2014) to be a lasting work of art. As testament to this, the artwork was exhibited by Gagosian at Art Basel this year—and in this way, it has a lasting tangibility that much of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s output is not afforded. In some instances, though, the temporary nature of their work allows the magic of their work to be preserved in time: the clear polyethylene used for the earliest wrapped objects has discoloured over the years to the extent that the yellowed surfaces look remarkably less like the crisp objects first photographed in the early 1960s.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude often shrugged off the notion that there was any artistic meaning behind what they did. But their work was nonetheless radical in its endeavour. In Valley Curtain (1970–72), for instance, the artists installed 200,200 square ft of woven nylon in a luscious canyon in Colorado, with vivid orange fabric stretched across a gap in the Grand Hogback Mountain Range. It took over two years to realise the project and around one hundred workers and volunteers to install the curtain; it only took 28 hours for gale forces to see the curtain uninstalled at short notice. But, the intentions behind Valley Curtain had been met. Speaking to The New York Times at the time, Christo explained that “[aesthetics] is everything involved in the process—the workers, the politics, thebnegotiations, the construction difficulty, the dealings with hundreds of people.”

That sentiment is evident in other largescale installations by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, most notably perhaps in Running Fence (1972–76), for which they had to liaise with almost sixty local ranchers (let alone government bodies, and multiple public hearings) to install 24.5 miles worth of white woven nylon—4.4 metres high, and 2.15 million square ft in total—attached to 2050 steel poles, stretching across land and sea in Northern California.

It took several hundred workers to install the fence over many months, and was visited by as many as 2 million people in the two weeks that it remained in place. When Jeanne-Claude passed away in 2009— serendipitously, both artists were born on 13 June 1935—Christo continued to realise the many ideas and projects they had conceived over the years and, as Spalding noted, continued to refer to his artistic partner and wife in present tense. This is important: though their work was made by both artists, for many years it was realised under Christo’s name only—for ease, or in response to the still-hostile reception women artists received—though they later reattributed their works under both their names in the 1990s. Nonetheless, Jeanne-Claude was often referred to by names such as “Mrs. Christo”, despite often being the spokesperson on both of their behalfs. That their work was made together, then, was, for many years, unnoticed, or was simply ignored. Together, though, their ambitions had been bold from the beginning of their professional, and personal, partnership.

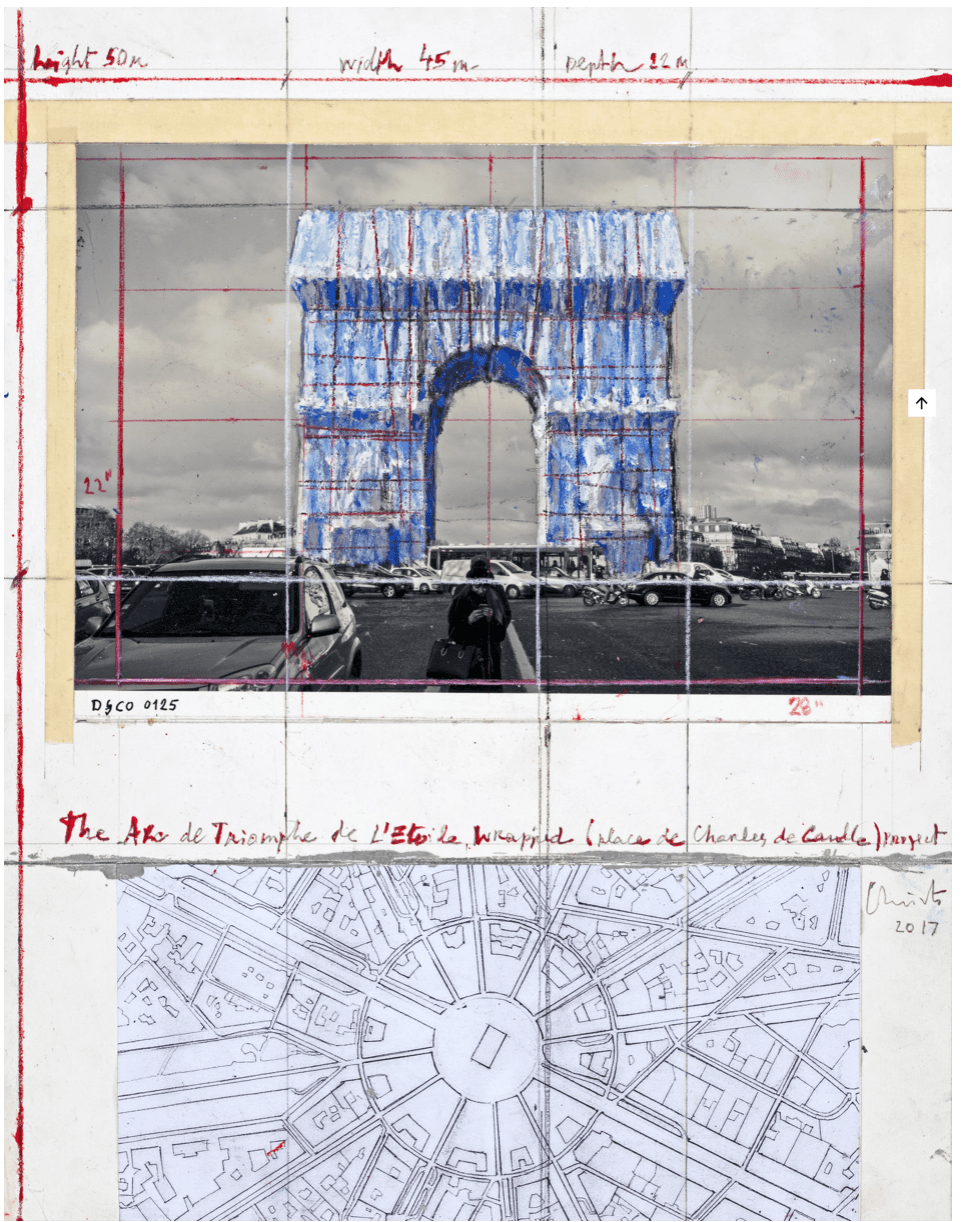

L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped (1961–2021) was one of the earliest works that the artists dreamed up while Christo was using a small maid’s room nearby as studio 1960s. In anticipation of an exhibition of their work at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in March 2020, Christo had planned to celebrate the opening of Christo et Jeanne-Claude, Paris! by staging L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped. Yet, with the arrival of the Coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing lockdown that spring, both the exhibition and wrapping were postponed; and in May 2020, Christo passed away, aged 84. Nonetheless, it had been the artist’s wishes that the installation would go ahead, and so, in September 2021, L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped was eventually unveiled in Paris for a period of sixteen days. Completed sixty years after Christo and Jeanne-Claude first envisioned the scheme for wrapping the Arc de Triomphe, the installation was overseen without the supervision of either artist. As with The Pont Neuf Wrapped, the woven polypropylene used for this installation shimmered and gleamed in the light; the sculptural reliefs that decorate the arch smoothed over. For Christo, the project represented freedom: the freedom to take over a public monument temporarily. But its concealment also draws our attention to the ideas of two artists who, through their close collaboration, reveal that it was never just Christo dreaming up such ambitious temporary artworks, and nor was it Christo and Jeanne-Claude: the aesthetic, and the legacy, of their work lies not just in the archive of collages, drawings and photographs of their work, but also in the stories and memories of the many hundreds and many millions more visitors to their temporary installations.

Even in the aftermath of L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped—the project that has perhaps come to symbolise the work of Christo and Jeanne-Claude— their legacy continues to unfold (as the impetus to celebrate fifty years of Ocean Front suggests). In September this year, the curator and conversationalist Hans Ulrich Obrist will release a book of his encounters and interviews with Christo, conducted between 2012–20. The artists may no longer be here to undertake their projects in person, but as Alloway wrote of their work, “meaning follows the making of the art, instead of preceding it”.