In 1956, the artist Joan Miró was at the pinnacle of his career. Aged sixty-five, he had gained international recognition and recently moved into his newly-designed studio by the architect Josep Lluís Sert in the outskirts of Palma de Mallorca. With its open plan arrangement, terracotta floors and long skylights, the central room of the preserved Sert Studio—filled with canvases and natural Mediterranean light—pays homage to where Miró once worked with intensity and perseverance until his death in 1983.

Born in the Catalan metropolis of Barcelona in 1893, Miró was raised by a family of affluent craftsmen. His father, a successful goldsmith, was reluctant to encourage his son’s artistic aspirations, instead pushing him to follow in the family tradition and find employment in business. But Miró’s prevention from pursuing art created great unhappiness in his youth (he suffered a mental collapse when forced to work as a clerk). Known to be a daydreamer, he struggled with the confinements of school life. Despite his father’s dissuasion, Miró eventually enrolled at the School of Fine Arts in La Llotja—the same academy where Picasso had previously studied—followed by the Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc.

A crucial turning point in his artistic career occurred when Miró moved to Paris in 1921, where he would settle for several years. Here, he quickly befriended artists affiliated with Dada, Cubism and Surrealism, who introduced him to the Montparnasse café scene. These were formative years for the young Miró, mixing with influential artists and poets of the day, like Picasso and Francis Picabia, as well as the leader of the Surrealist group André Breton. Breton would later hail Miró as an artist who found a way to depict the “poetic reality” of life and was “the most Surrealist of us all.”

Inspired by the aesthetic strategies of Surrealism, Miró made space for the subconscious in his paintings, blending an impulsive stream of consciousness with carefully rendered compositions that led to his trademark of biomorphic, colourful abstractions. “The Surrealists didn’t consider painting as an end” he wrote to a friend, many years later. “With painting, in fact, we shouldn’t care whether it remains such as it is, but rather whether it sets the germs of growth, whether it sows the seeds from which other things will spring.” This attitude of eternal progress and discovery would propel Miró’s distinctive painterly practice.

Miró always maintained a deep connection to his roots—to the landscape and culture of Catalonia. In 1929, he married Pilar Juncosa, a woman from a family with a long history of living in Mallorca, and with whom he had his only child, Maria Dolors Miró. Over the course of fifty years of marriage—lasting until Miró’s death—the couple enjoyed a close relationship, with the artist regarding Juncosa as his “ideal companion”.

In the late 1930s and on the eve of Civil War in Spain under Franco, Miró remained in Paris in exile, though he eventually returned to Spain with his family in 1941. After the Second World War, the Miró family moved to Mallorca—a place that characterised Miró’s childhood (his mother was from Mallorca), and offered a change in scene as a creative backdrop for the artist following the immense turbulence of war. He entered into a period of fertile withdrawal from the outside world, cultivating his practice with dedication. “I work like a gardener” he confessed in 1959, a metaphor revealing his humility regarding the daily act of painting.

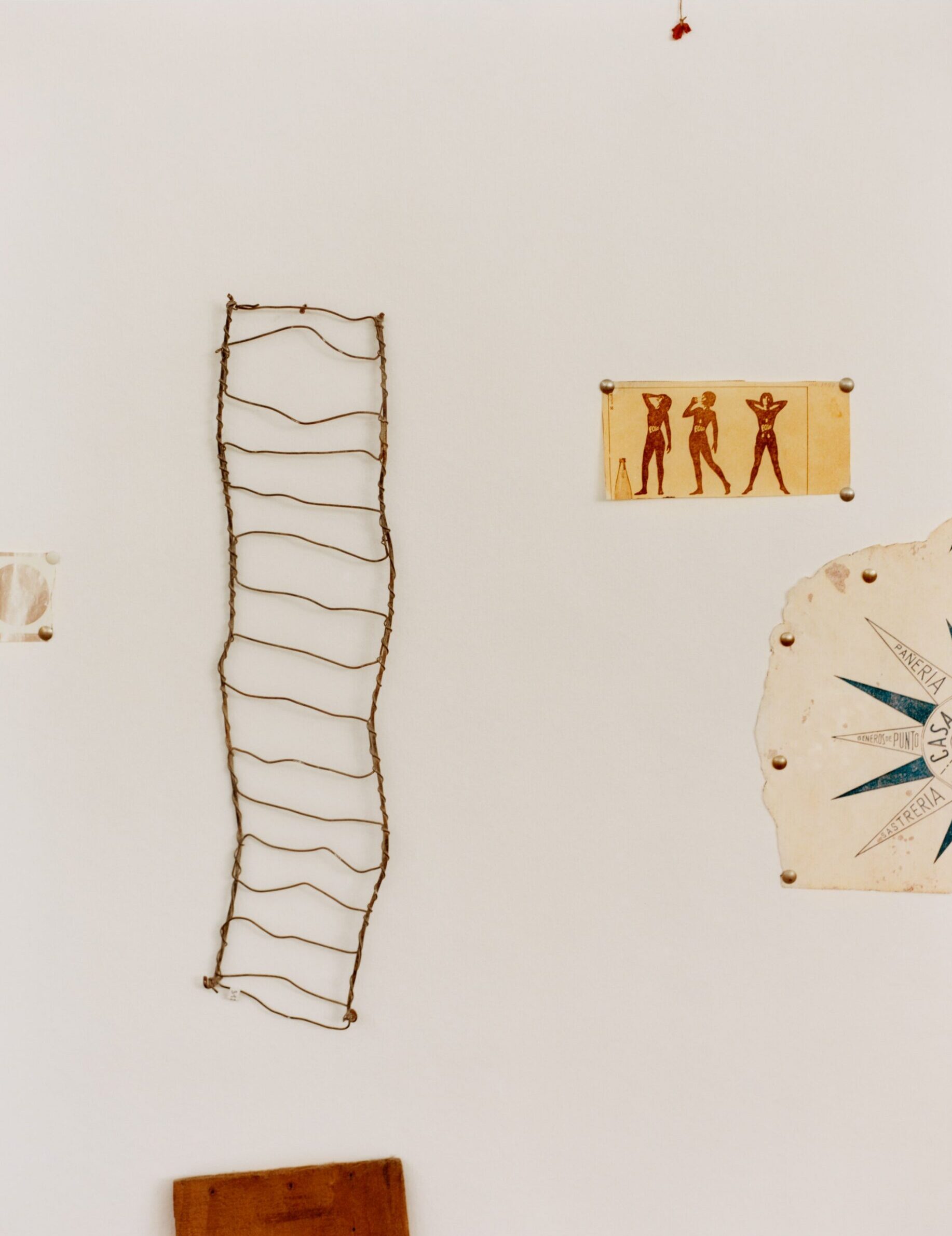

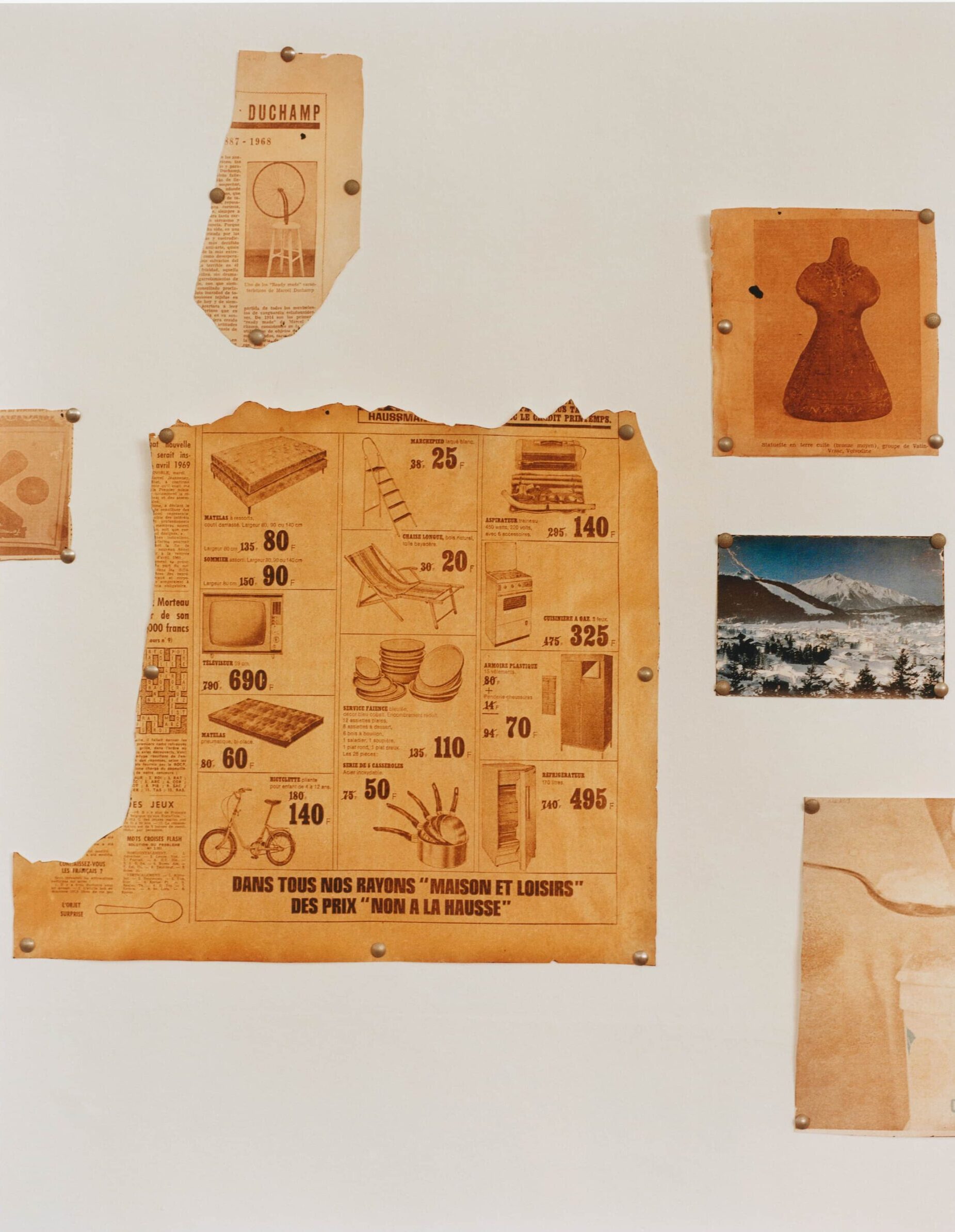

The Sert Studio came to resemble Miró’s studio of dreams. Having previously worked closely with Le Corbusier, Sert was considered a pioneer in modernist architecture, one concerned with creating harmony between aesthetics and functionalism. With more space at his disposal, Miró spent time in his new studio observing his own works, reflecting on his archive and finding inspiration from the unique architectural surroundings created by Sert, who once proclaimed that “architecture can itself become a sculpture.”

Known to be excessively orderly, Miró’s studio reflected his strict discipline and abundant creative energy. “Nothing is left to chance, not even in his daily habits: there is a time to take a walk, a time to read, there is a time to be with his family and there is a time to work” his biographer Jacques Dupin would observe. Miró woke up at the same time every day around 7am before showering, taking breakfast and going to his atelier until lunchtime, followed by a siesta and a prompt return to work for the rest of the day, until evening. He worked silently and alone, though in between painting he was known to read poetry and listen to music, usually classical or jazz. Led by his interiority, Miró confessed that he was always working, even in his sleep and while he dreamed—his entire lived experience was infused in his artistic outlook.

A prolific painter, Miró’s vision significantly contributed to the direction of modern art history. Defying easy categorisation, his brilliance lay in his originality and non-conformity, distinguishing his practice from his contemporaries and developing a distinctive aesthetic that shaped an entire world reflecting his interiority. But most of all, it was Miró’s everyday perseverance that underpinned his work. “Things come slowly” he once confessed. “My vocabulary of forms, for example, I didn’t discover it all at once …it formed itself almost in spite of me”.