In 1992, John Baldessari visited India for two months. For an artist best known for works that explored his native California, it was a different kind of trip to what he was used to. The works that Baldessari made out of that two-month stint have also been largely overlooked in his rich oeuvre, often not even making a footnote in histories of his lucrative career. This year at its galleries in London and Berlin, Sprüth Magers—who represent the John Baldessari estate—have embarked upon re-addressing that discrepancy, and its exhibition, Ahmedabad 1992, brings these works to a larger audience.

Baldessari was invited to stay with the Sarabhai family (known for their textile manufacturing and arts patronage) in Ahmedabad at their estate for an artist residency. Villa Sarabhai was designed by Le Corbusier and built between 1951–55, a brutalist complex set amongst luscious 20-acre grounds. Many artists were invited to stay at the villa by the family in the twentieth century, including Alexander Calder, Isamu Noguchi and Charles and Ray Eames; Robert Rauschenberg described it as “The Retreat”.

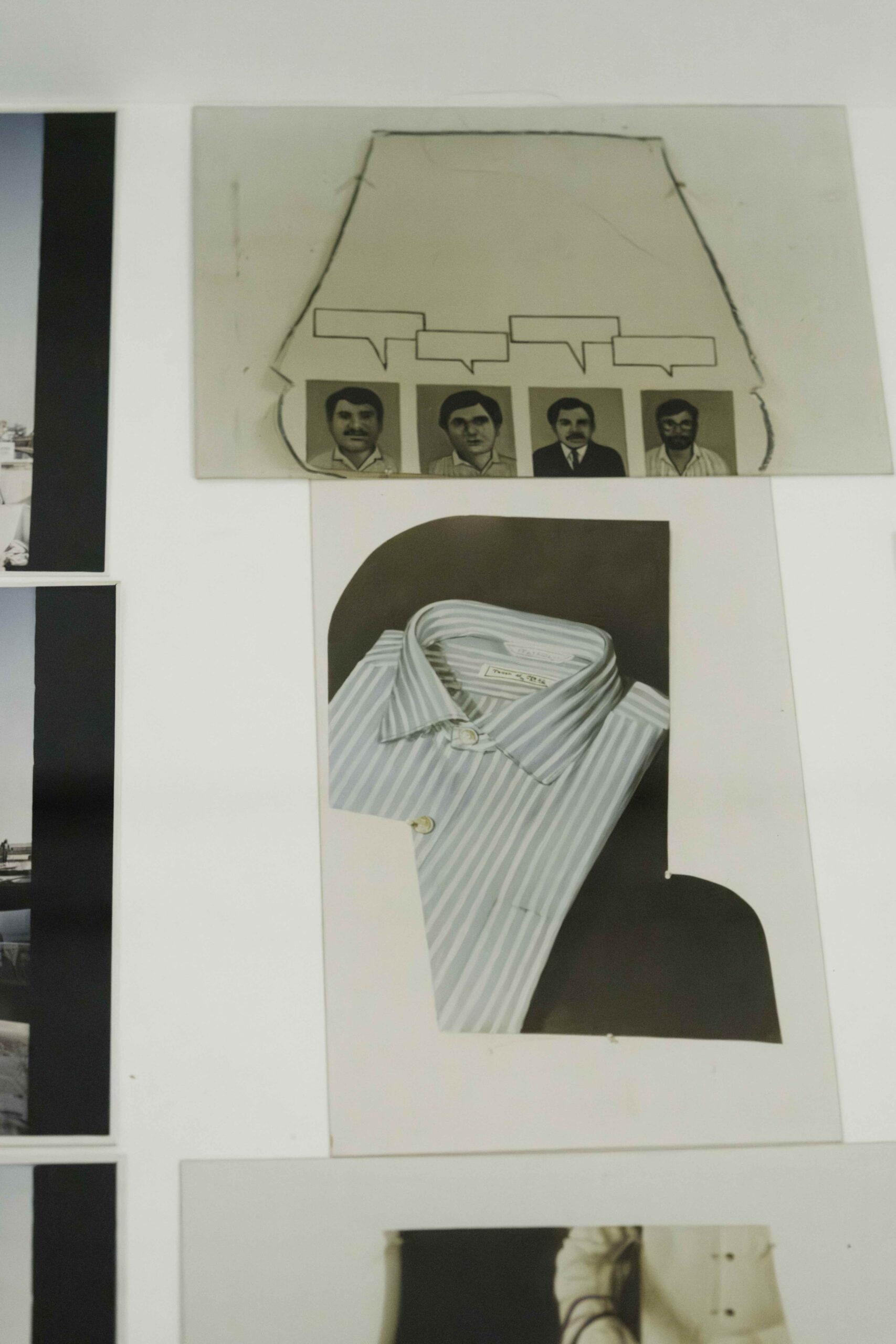

Photographs taken at the time of Baldessari’s time at the Villa Sarabhai show the artist, then in his early sixties, in conversation with other residents at the retreat; in another, he stands tall, amongst piles of red chilli peppers: the Californian landscape switched out for another, equally as vivid and immersive, though in a way that the artist was unfamiliar. Those pictures of Baldessari were taken by the renowned photographer Raghubir Singh, whom he had met at the villa. As the curator Shanay Jhaveri notes in an essay to accompany the exhibition catalogue for Ahmedabad 1992, Baldessari would later write about his encounter and recall of his time in India that he struggled to photograph what he found: “The problem is the visual bombardment and overload.”

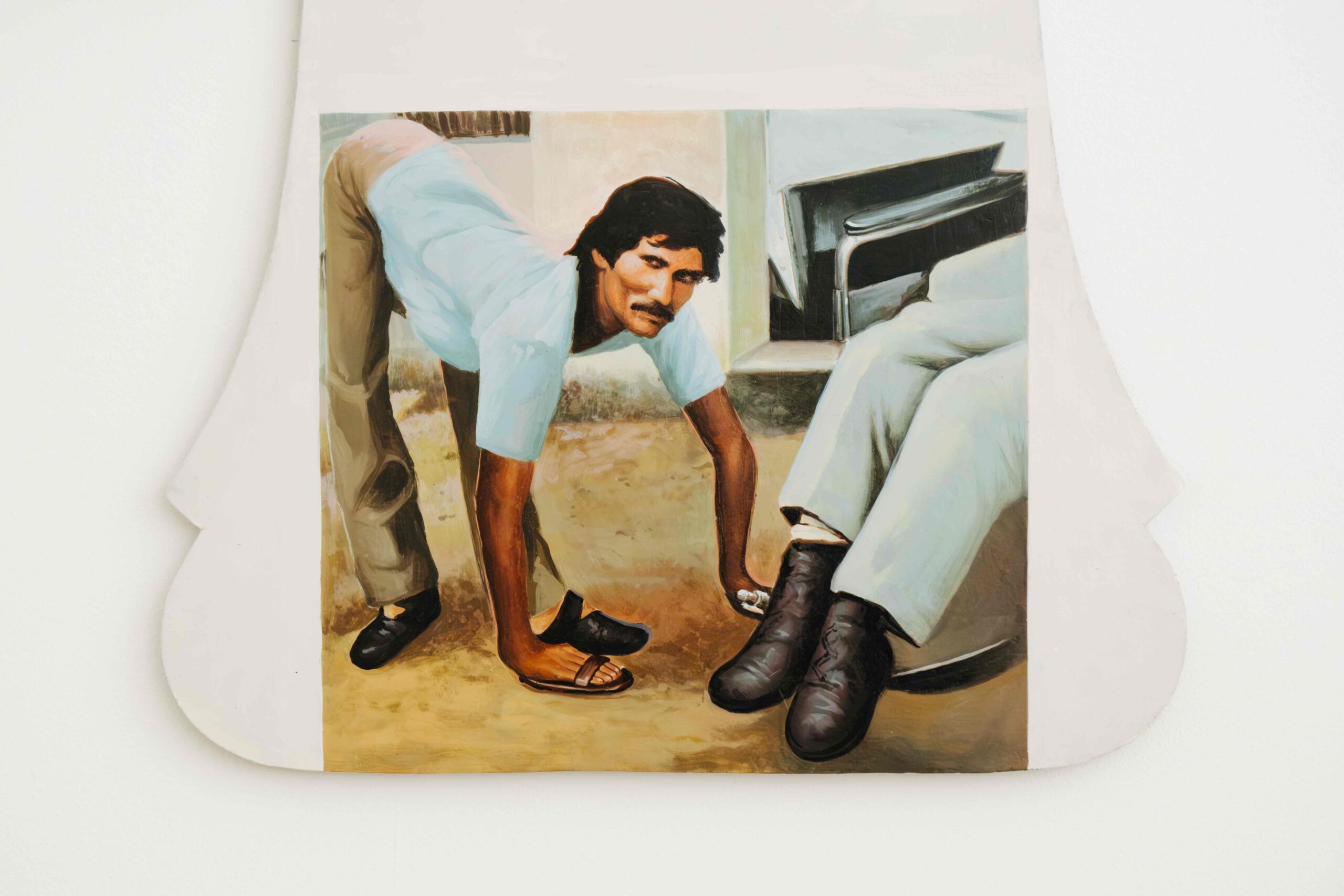

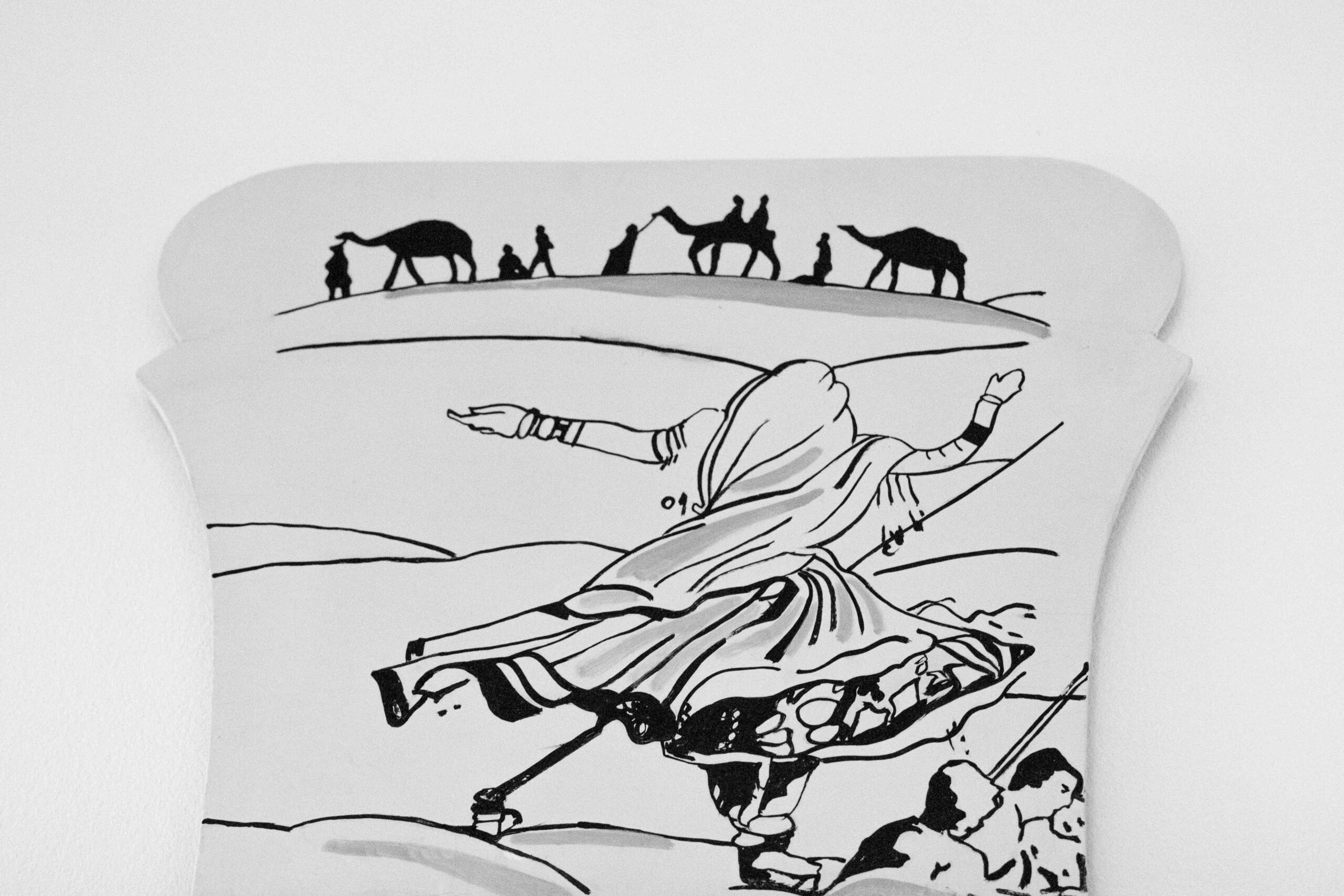

For an artist whose work engaged so often with photography, such an admission was part of how Baldessari responded to this unfamiliar environment. The works that came out of this trip to Ahmedabad capture the richness of the visual stimuli that Baldessari found himself exposed to. Combining a range of media in multi-panelled forms, the artist collaged photographs he had taken (his struggle to capture the landscapes are, contrary to his recollections, not visually apparent), with areas of paint, found imagery and handmade paper made by Baldessari at the Gandhi Ashram during his visit.

Baldessari also incorporated painted mudflaps and panels of Formica into these works, fashioned alongside his assemblage of photographs and found imagery and ephemera. His experimental approach, with aspects of a work often existing outside of the frame, captures a sense of the playful humour characteristic of the artist’s work more generally—while also giving the impression of someone trying to grapple with an encounter hitherto unfamiliar (by also making the viewer look across the material that he collates in different ways). Baldessari created this series of work back in his studio in California, and in sketches and photographs from his archive—and on show at the exhibition—the process of confronting that experience is laid bare.

Both Jhaveri and Mario D’Souza—the curator and writer who also writes an essay for the Ahmedabad 1992 catalogue—draw attention to the extent to which Baldessari engaged with what he encountered in India. For Jhaveri, the series is neither about India nor the artist himself, but both: “Perhaps it is this quality, of trying to grasp a landscape that is ever-shifting, that distinguishes this body of work and marks it at as slightly apart from the rest of his oeuvre.” While as D’Souza observes, “Baldessari never claimed to know India or understand its complexities, he remains cognisant of his position as a visitor and uses that as his approach.”

While there are clear differences in Baldessari’s works from his time made in response to his visit to Ahmedabad, the series can also be seen within the artist’s wider oeuvre. The painted mudflaps that Baldessari collected, for instance, were the work of billboard sign painters that he encountered during his visit. The artist recalled, in an interview with Jhaveri, that he enjoyed visiting the workshops, watching these billboards being painted. In incorporating the works of these painters into his panels on India, we can see how Baldessari looked across a range of planes to shape an impression of place. As he told Jhaveri, the images that were painted onto the mudflaps were found, by Baldessari, in magazines and newspapers.

The practice of engaging sign painters into his work recalls Baldessari’s formative conceptual projects of the ’60s, hiring sign painters to create his text paintings—an attempt to remove all traces of the artist’s hand from the process of artmaking.

This creates a neat link between some of Baldessari’s most renowned work with a body of work that has been, in contrast, significantly overlooked. Though, it seems unlikely that Baldessari included the work of local sign painters in Ahmedabad to make as similarly conceptual a point as he had done in the 1960s. Rather, and as the artist recalled in an oral history with the Smithsonian Institute, it can be seen through the lens of collating, cataloguing and foraging material.

What is apparent when looking at the kinds of images that Baldessari used for this series of work was that the early 1990s was a period of flux. In India, as elsewhere, new technologies were transforming connectivity across time and space: we see this in mudflaps that depict high-speed trains and abstract depictions of the internet. But these “advances” coexisted alongside established patterns of life and work, a juxtaposition that the multi-panel nature of these works captures.

The trip also came at a time when Baldessari’s public reputation had reached new heights in his native United States, his visit bookended by a 1990 retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and creating an advertisement for Gap in 1993. Baldessari’s trip to Ahmedabad was short, but significant. As he told Jhaveri, “I wanted the work, of course, to reflect my time there, which was very limited—I think, you know, a couple of months. Trying to absorb all of that, this completely different world. I mean, there’s a lot to process.”