The choreographer Damien Jalet is best known for ethereal, earthy – dance performances, such as Vessel (2015) or working on cult films, like Luca Guadagnino’s 2018 remake of Suspiria Dario Argento’s 1977 horror classic set in a dance school. But as Jalet tells Present Space over Zoom, it was theatre that he first intended to work in. Born in Belgium, he was studying at the National Institute of Performing Arts in Brussels where he was confronted with a culture barrier that he struggled to overcome. But, he says, “it was the ‘90s and there were a lot of transdisciplinary things happening especially in dance [which] was more open than traditional theatre. I actually started dancing because I was dancing in clubs.” It was this that would see Jalet’s transition into dance and choreography when he was spotted by a choreographer. “It opened up a new world,” he recalls – “it was a space of freedom.”

It’s this route into dance and choreography that, Jalet says, informs the interdisciplinary nature of his work. Vessel, for example, was the first of three collaborative performances with the Japanese artist and sculptor, Kohei Nawa. Ever the transdisciplinary collaborator, Jalet’s work with Nawa became the focus of Vessel / Mist / Planet [wanderer], a book published in May 2022 that aims to “decipher the world of their works.” The pair’s collaborations, which also include Planet [wanderer] and Mist, certainly feels like a world within itself, and as Jalet says, from the start it was never their intention to create something that was just a performance. The bodies of the dancers become something sculptural – and Jalet and Nawa actually created a series of sculptures taken from 3D scans of the dancers, which were exhibited at the Arario Gallery in Seoul, Korea in 2019. The sales of the sculptures, in turn, enabled the collaborators to oversee performances of Vessel on a bigger scale.

There is a lot of layering at play in Jalet’s work, then, where performances are interpreted through different mediums, scales or vantage points. In the case of Les Médusés, a 2013 dance performed at the Louvre in Paris, Jalet’s work would be reinterpreted on a much larger scale, for the camera. Jalet had prepared his dancers for that performance by getting them to watch Argento’s Suspiria. And it was Les Médusés that convinced Guadagnino that Jalet was the choreographer for his Suspiria remake. The film was scored by Thom Yorke, and perhaps in true Damien Jalet style, the choreographer went on to work with Yorke on Anima, the short film that accompanied Yorke’s 2019 album of the same name.

Throughout Jalet’s oeuvre, there’s something visceral and transfixing about the ways in which he morphs and weaves the human form in new ways. This flexible approach to dance and the body extend to the ways in which he also adapts his skill and finesse to work with collaborators from Madonna to Marina Abramović. As Jalet tells Present Space, “collaboration is the motto behind everything. I always try to experiment [with] new forms and new ways of collaborating. Dance [makes it] possible to discuss with other mediums; that’s why I love it, it has the potential for conversing and collaboration.”

When you travel a lot, it gives you another perspective on your own identity. It has always [been] important to me to get out of anything that feels restrictive, and it’s the same with dance. I always try to establish connections with visual artists, with designers, with musicians – people that I would not necessarily have any [other] connection with, but in a way, it’s about fusing our practices. I also have this with borders; I like to create in places that are far from home. I’ve worked in Mexico, Japan, Iceland, Scotland, Australia. Crossing the border of home and also of my own discipline is always extremely exciting. You are being pushed to adapt and you are out of your comfort zone. In a way, you are pushed to explore different sides of your identity. I think we all are very interdisciplinary; we have a lot of people within us, and I like to explore those connections. When I work with visual artists, I become a little bit of a visual artist myself, or at least I take on their perspective. And it’s the same when I work with a musician, I dive into their world – or when I work with a filmmaker, I’m trying to see through their eyes. I really love the sense of exploration that comes with it. I think of creation as [being] the result of a conversation or a meeting.

I think my collaboration with Kohei is one of the most meaningful of my career. And it’s great to talk about this, especially when we’re talking about fusion, because it’s literally in the work. When we [first met], the language and culture [barrier didn’t help] – he barely spoke English. I approached him after seeing some of his work back in 2013 and I think there was something that I could really relate to, [in particular] Pixcell – deers that he would cover with thousands of glass bulbs. And there was also Foam, which was an installation in which a landscape made out of foam was constantly transforming. It was kind of like a light sculpture, with the audience walking within it. After we finally met, the body became the starting point [of our collaboration]; for example, how can you also use the body as a place to explore the non-human or something that is at the boundaries between human and non-human?

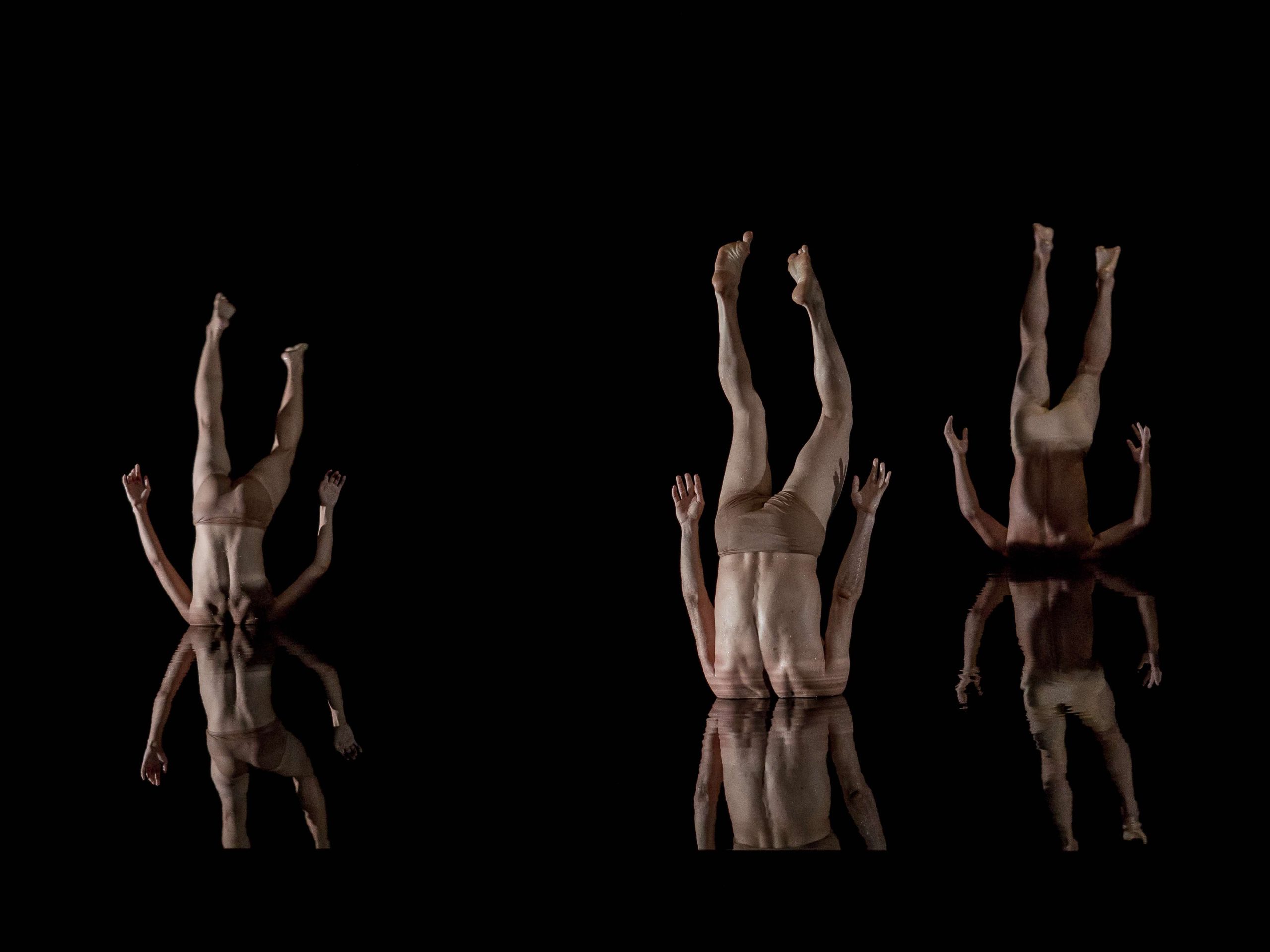

With our first collaboration, Vessel, we started playing with different materials [in relation to the] shape of the body-a shape that comes from millions of years of evolution on a planet that has gravity, an atmosphere, created by non-human entities. The air we breathe has been created by organisms that at one point used the connection between light, water, minerals, just to grow. And I think art can be this place where you start re-questioning things, things that you take for granted such as the body. We are shaped by the planet and gravity, so with Vessel we used the confrontation of the body with different materials to make visible some of the things we take for granted. Gravity is a recurring theme in both of our work, it is something I always like to explore because it’s the common language of everything. It’s an invisible force that we are constantly feeling the pull of, and you can use that force to sculpt, to paint, and in dance. I like to question the cliche that dancers defy gravity; I think you can also say that they converse with gravity – that the idea of surrendering to it can produce some very beautiful things as well.

I think we were really interested in creating a language. I never wanted him to design a set – you know this kind of collaboration, with one set designer making a set with dancers performing in front? I’m not interested in that. Instead, it was more about our common obsessions and finding something that becomes so entwined and intricately connected that it becomes something new. We started Vessel with the dancers positioned as if they were headless bodies, which became about exploring how you can evoke the non-human and create a mythology through anatomy.

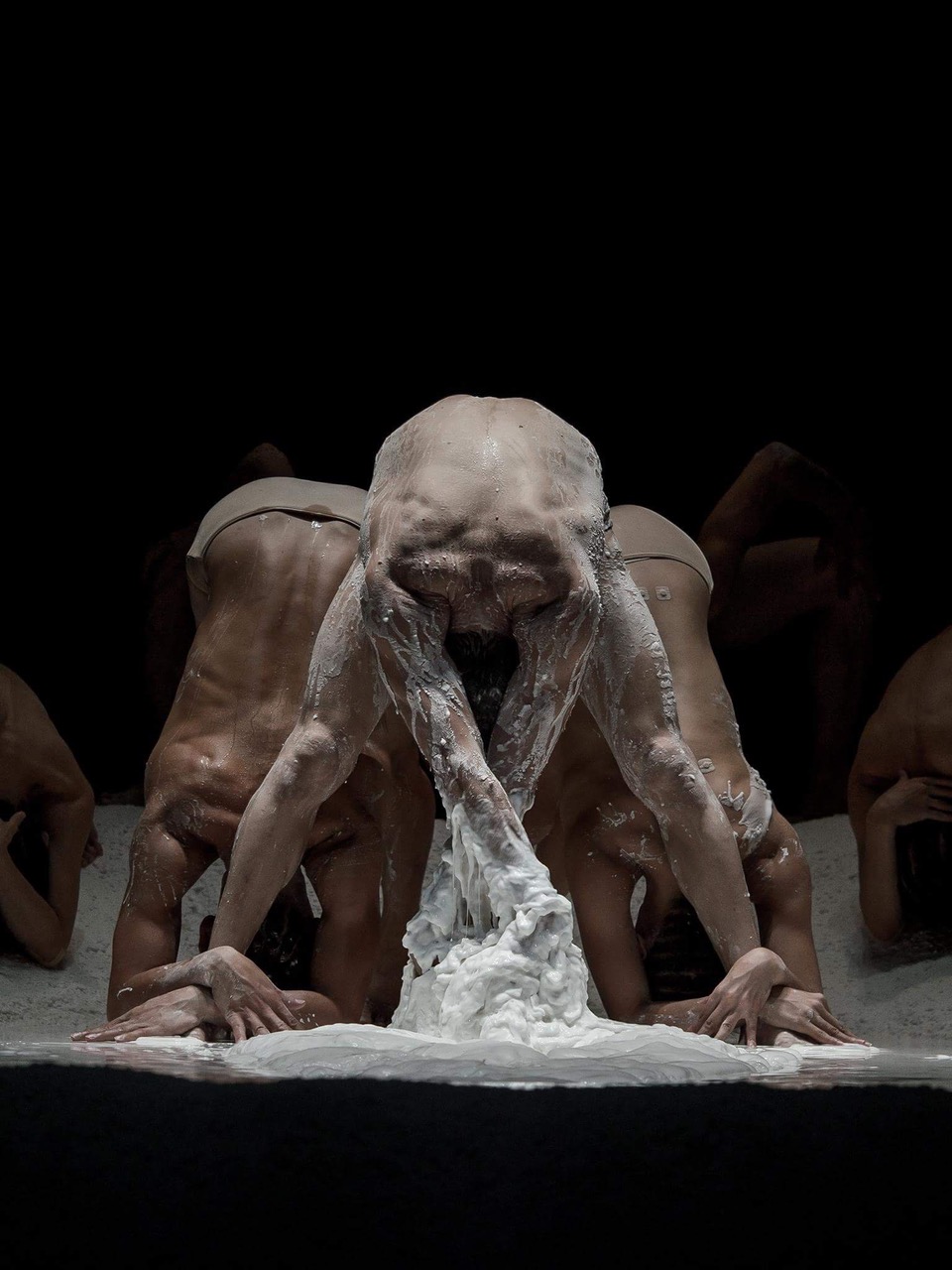

And then for Planet, we started with the idea of the body again, but as a root. The word planet actually comes from the Greek term, planaomai – to wander, the wanderer. There was something so human about that word. We move, we’re in constant exile, and the planet itself is in constant exile because it’s always moving through the cosmos. [As with Vessel] the inspiration for the work was the Kojiki, an early Japanese book of myths and legends. In it, there are three levels – the underworld, and the world above the clouds, but there’s also the middle ground – the Central Land of Reed Plains – which we’d call Earth and which is where Planet takes place. We used slime and different kinds of matter to re-question our presence and our condition on earth, and the fact that we are matter too. The bodies of the dancers were also confronted by silicon carbide, a material found in meteorites. It’s a non-Newtonian material (which changes state under pressure); it liquifies in slow motion, and reveals gravity in slow motion. So it’s not just a dance piece or just a sculpture, but a choreographic sculpture, or a sculpture in movement. I don’t know how to label it, but it’s definitely something that is in between, like the exploration of and in between.

Skid is a more direct approach [to gravity], yet it’s also abstract. And again, there’s a spatial association – it’s very dreamy. (It’s actually going to be performed a lot next year, in London, Sydney, as it’s going to two other dance companies this year. I was just working on it two days ago, after three years since the pandemic stopped.) It was originally created for the Gothenburg Opera Dance Company, which has extremely talented dancers from all over the world. With this piece, the challenge was to actually deconstruct their technique, to rebuild something new. I love the idea that, by creating new limits, there’s an infinity of possibilities. You invent your own rules, and you don’t start from something that already exists; you choose what you want to develop, and which techniques. You develop the movements; you can invent them.

Well, it depends. The Paris Opera asked me to work with them at the last minute in 2020, and I ended up asking (French photographer and visual artist) JR to collaborate on the sets and costumes. Days before the premiere of the piece Brise-lames, which was supposed to be performed in front of the theatre safety curtain, the second lockdown happened. So, instead, we filmed it with six cameras and then spent time editing it in order to translate the experience of the piece into a filmic experience. (Brise-lames was shown on French television). The same happened with Mist. It was supposed to be 20 minutes long, and then it was postponed a year [because of the pandemic] – and we ended up having to run it as a full evening performance because the law didn’t allow intermissions. So, we made it into a full-length feature, filmed by the director Rahir Rezvani.

When a filmmaker approaches me, I know from the beginning that I’m not going to work in the same way as I do on a performance for the simple fact that the medium is different. With film, you can have a moving perspective, which you don’t have when you know someone is going to be sitting in the back row for an hour and see only one perspective. With film, you can get so much intimacy. You can go from top, you can go from behind, you can go around. Or, when Madonna asked me to help choreograph the Madame X Tour (2019). It was interesting because she was looking for intimacy as someone so famous and so used to massive crowds. It was great to explore that side that she wanted to explore, that was out of [her comfort zone]; I always love to create things that are a bit unexpected.

When we did Anima it was the same. Thom wanted to make a film that was supposed to be very short – but then he asked Paul Thomas Anderson to direct it, and then it became a Netflix thing. But even though it got a much bigger budget, the spirit of it stayed the same. We never had to adapt the vision, or had people saying, “Can you make it a little bit less weird?” It was always about connecting with our instincts and tuning different minds together. And I want to work like that. I’ve worked on big projects and my work has been opened up to more people, but I never want to just find myself in a situation where I’m asked to adapt to make it more audience friendly, or whatever. And I’m happy to have worked with people so far that have never had this in mind.

I think collaboration always has to start from a place of deep interest in the other person’s work – and then it’s just the exploration of this. That has to be mutual. If that’s not the case, I would say don’t do it, because it can go really wrong. And I think it can be potentially damaging because you can end up finding yourself stuck with someone or with another artist, and you can limit each other. That’s why it’s so important to really question before you start what motivates it. Deep desire has to always be at the root of it, because it’s never going to be easy, even with that, you know?