The First Invention: Fire

A stick digs sharply and rapidly into a groove, releasing a smoky heat. Eventually, enough energy is generated to give light to a handful of kindling, and there begins a fire. This action represents a huge step forwards in our transformation from mere primates to modern day humans. From here on in, food will be cooked rather than captured and eaten raw, nights will be warm and safe from predators, and the potential of human invention would become limitless.

Although the first recorded use of fire dates as far back as 800,000 years ago, the scientific consensus points to its controlled manipulation becoming part of the daily lives of our ancestors around 300,000 years ago. The act of cooking was so effective that it quickly spread to all corners of the Earth. Today, not a single remote indigenous community has ever been contacted that does not harness the power of fire.

The simple act of generating friction to create a flame may well have sparked the endless march of human progress, advancing us from the simple wooden and stone tools we had used for millions of years to multi-stage, process-driven solutions to every imaginable problem. Richard Wrangham, the author of Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human (2009), even credits the use of fire as a crucial factor in the physiological evolution of human brains. By outsourcing some of the work that was previously being taken care of by our digestive system, he posits that early human ancestors—most likely Homo erectus—began using fire around 2,000,000 years ago, allowing enough time for it to have impacted our evolutionary trajectory. Cooking, he argues, increased their calorie budget by making both plants and animals easier to digest, permitting more energy to be allocated for their growing brains and incessant thinking. In modern humans, neural activity accounts for around 25% of the body’s total energy expenditure, compared to 3 to 5% in other large mammals, underscoring the importance of an energy-efficient diet.

Early Inventions

The prevailing argument, however, is that humanity’s drastic shift towards becoming a highly intelligent and technological species stems not from cooking, but from the emergence of complex language in Homo sapiens around 70,000 years ago. While acknowledging the beneficial impact of fire, in his seminal book Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari argues that this linguistic breakthrough was the key driver of the ‘cognitive revolution.’

It is thought that a random gene mutation may have given rise to advanced communication skills in Homo sapiens, speeding up the rate of adaptations and behavioural changes. This great leap allowed early modernhumans to create fictions about themselves, each other and the world around them. For the first time, they could create value concepts around objects and contemplate their own existence, inventing cultural and spiritual ideas that helped them to connect with one another, facilitate the sharing of information, and rally around common causes. This newfound impulse to imagine and abstract would feed into all later inventions, both physical and conceptual, and the technological advancements of our species.

Between 30,000 and 70,000 years ago, Homo sapiens went on to explore and manipulate the environment like never before, their successful venture out of Africa coinciding with the development of many technologies that would come to define modern–day humans. Their encounter with harsher environments led them to create protection against the elements, using rudimentary needles and animal hides. Clothing changed them fundamentally, acting as a way of signalling status and tribal membership, as well as introducing concepts of privacy, modesty and gender.

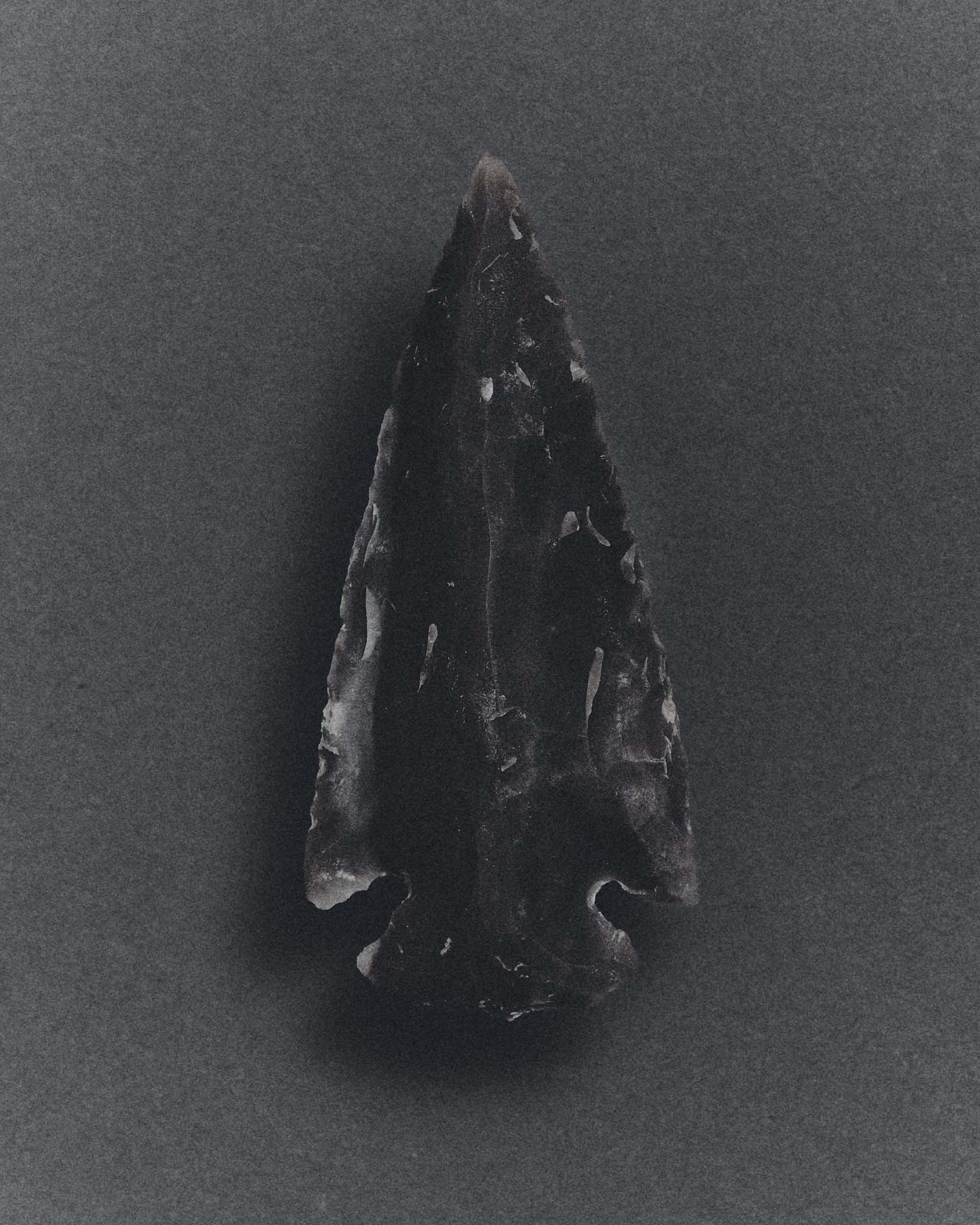

During the period that followed, Homo sapiens also shifted towards the use of bow and arrow, building upon earlier primitive spear-throwing devices, known as atlatl. This new technology was able to harness the stored energy of string—made of animal sinew, guts or plant fibres—in order to release projectiles with speed and force, and from a greater distance. It was a development which made hunting more effective, safe and specialised.

The earliest evidence of wooden canoes, on the other hand, is from around 9000 years ago. This invention likely evolved convergently, building on earlier iterations made from reeds and used as a way to fish more effectively or move cargo downstream with far less effort. As the technology was refined, boats permitted our ancestors to travel between land masses and colonise previously uninhabited territories, effectively becoming the prototype for all modern-day, long-distance vehicles.

By improving quality of life and survival chances, inventions such as these enhanced and augmented the biological tools already at our disposal: intelligence, dextrous hands and binocular vision. This new form of intellectual evolution would supersede the importance of biological change in the coming millennia. While a bird’s nesting ability may be encoded in its DNA, humans were able to create dynamic solutions for providing shelter based on local conditions and prevalent materials. Thanks to structured language, the best techniques were able to be passed down generationally through abstract ideas, and much later, through books and educational systems that are typical of the developed, scientific world we inhabit today.

But how does the spirit of problem-solving and inventiveness of our ancestors, and that of the remaining isolated peoples of the world, resonate in today’s digital and fossil-fuelled age? As our petro–economies attempt to rapidly balance the scales with technological solutions to ever more complex social, environmental and personal health problems—many of which are caused by the very technology that is then called upon to fix them—indigenous peoples’ approach to life appears altogether slower, with fewer deadlines to hit, tipping points to avoid, and processes that require streamlining.

Remote indigenous communities may seem out of step with the ongoing cognitive evolution, with no written languages or formal education, yet they sustain themselves through a deep, intuitive understanding of their natural surroundings. Unlike Western economies that thrive on extraction and planned obsolescence, these communities rely on the ancient traditions of hunting, gathering and small-scale cultivation. Their technology is crafted from sustainable materials—boats from hollowed-out logs, spears from bamboo—while knowledge is passed down orally and through demonstration, promoting an intuitive approach to invention without reliance on formal engineering principles or digital tools.

Whether through trial and error or science-based deductive reasoning, technology has always been about maximising rewards with the least possible energy expenditure. Take farming, for example. The simple desire to reduce the amount of energy invested in finding food led to the agricultural revolution around 10,000 years ago. The first of our ancestors to cultivate plants inhabited Mesopotamia, a region that today spans Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel-Palestine and Turkey. As we transitioned from hunter-gatherers to growers, tilling the land and guarding our crops, we were able to establish permanent and stationary settlements. Following our long-standing relationship with dogs, the domestication of herd animals was the natural next step, providing easier access to protein as well as a means of transportation by horseback.

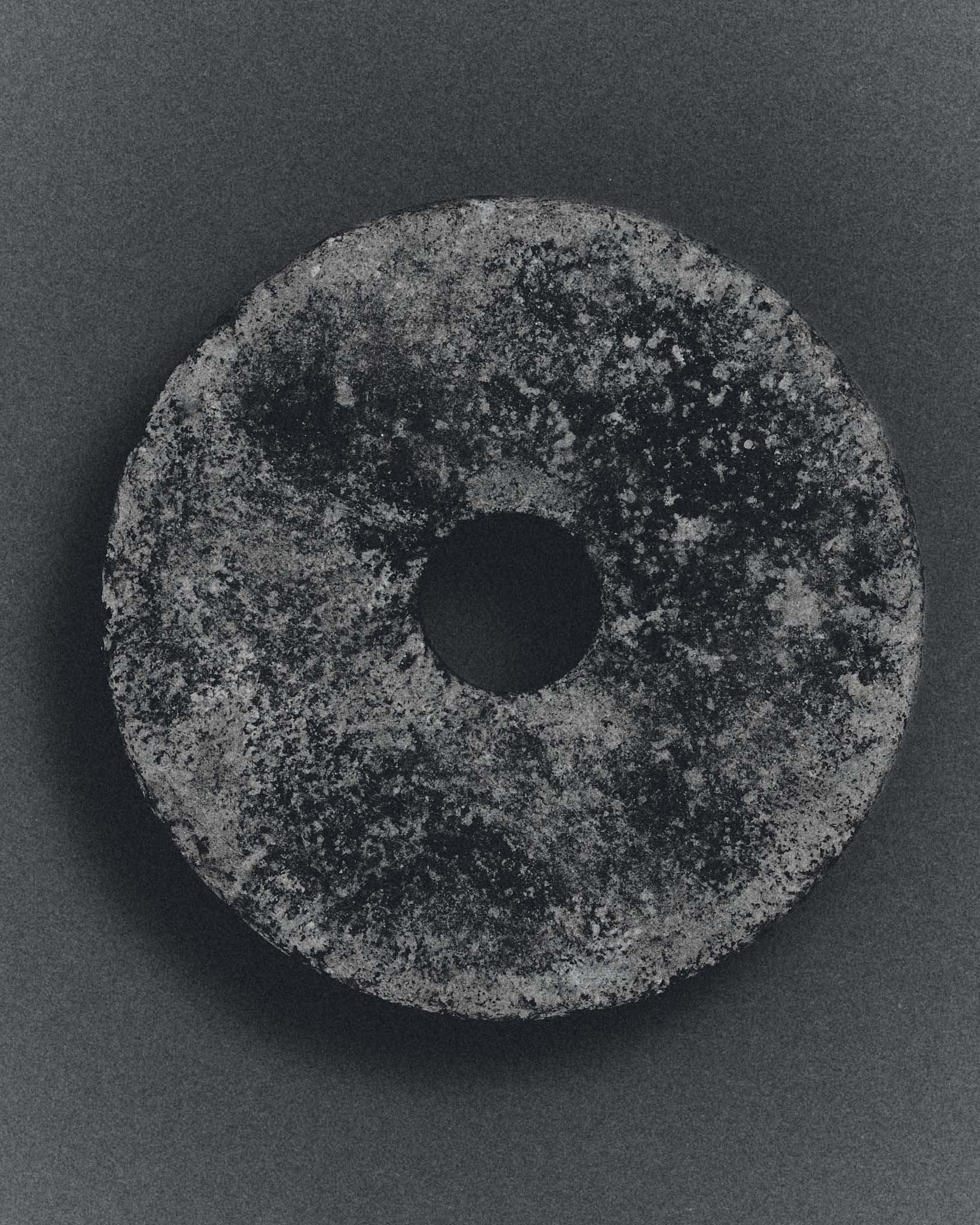

Between 4000 and 3400 BCE the wheel rolled around, with the earliest versions also found in Mesopotamia. Perhaps the single most impactful labour-saving invention ever conceived by man, it combined with an axle to overcome friction and facilitate the movement of heavy loads. Innumerable calories were saved in labour-intensive farming and construction, before the spinning disc went on to revolutionise transport around the globe. This marked the next step in our becoming a vehicle-dependent species, contributing towards a technological drive that would never cease turning.

Clearly, not every advancement can have effects as profound and long-lasting as the wheel. Some inventions that must have seemed revolutionary at their time of creation simply failed to gain universal traction. Obsidian blades, made from incredibly sharp volcanic glass, were once considered the ultimate cutting tool. Around 7000 BCE they were widely used in butchery, medicine and textiles across Mesoamerica, the Near East, the Mediterranean and Africa, but their brittleness limited their longevity. Bronze, and later steel, eventually replaced obsidian, offering greater durability and ease of sharpening. Metal knives became the archetypal cutting tool, even introduced through trade to many remote indigenous communities today.

That’s not to say that every invention which is replaced by an improved version should be considered a failure;there are, of course, a plethora of devices and concepts that left indelible marks on our species before disappearing. Crucially, what determines inclusion in internet lists of ‘Inventions that Changed the World’ is the ability to permanently shape the way we behave. Think of the virtually extinct landline telephone, and how people still use the expression ‘hang up’ to describe ending a FaceTime or a call on a smart phone. The printing press, on the other hand, is rapidly falling out of use because of growing digital consumption—but nobody would dare argue that this piece of machinery did not change the world.

Abstract rather than physical in nature, early alphabets are another highly influential—though often overlooked—human invention. The majority of people on the planet regard writing, just like speech, as a natural part of human behaviour, yet there are many extinct proto-alphabets that preceded Latin script and the 10 or so other major alphabets that we use today. The earliest known alphabetic writing system, discovered in the early twentieth century at an Ancient Egyptian turquoise-mining site, dates back somewhere between 1900 and 1500 BCE. Created by Canaanite-speaking workers, it adapted Egyptian hieroglyphs into a more efficient phonetic system and is considered the ancestor of many modern alphabets, laying the foundations for our ability to maintain precise records, build educational institutions and disseminate information on a massive scale.

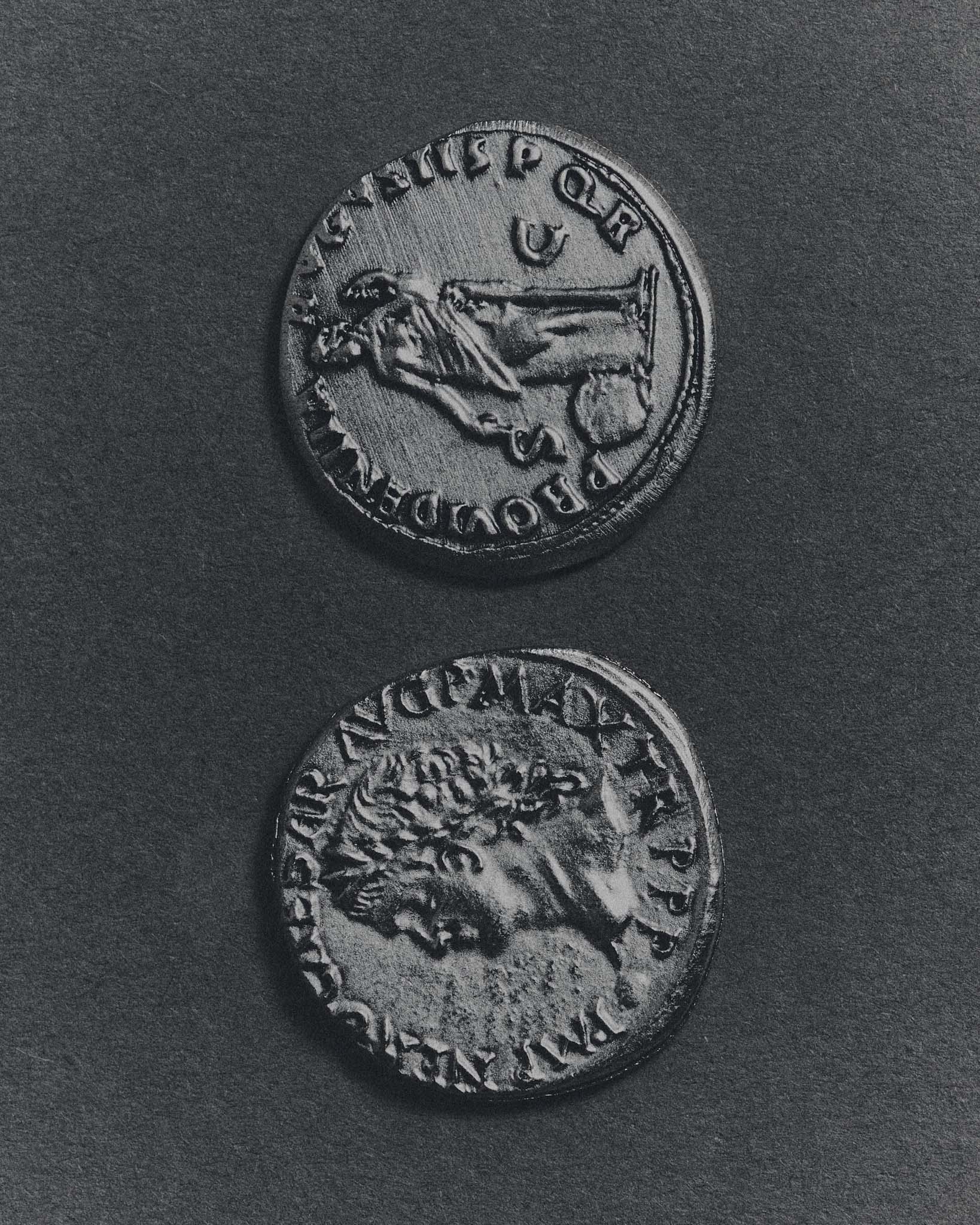

Still, language had a long wait until it could fulfil its potential in the modern era, with a few key physical inventions still to come. Emerging around 600 BCE was the world’s first monetary system in Lydia, or modern-day Turkey. Introduced by the immensely wealthy King Croesus, the currency’s different denominations were determined based on the metallic content of its coins; this monetary system quickly replaced traditional bartering systems that used cattle, grain, or other valuable goods. As money spread around the world, what began as a practical medium of exchange quickly became the currency of power, eventually transforming into the complex and predominantly digital financial systems we see today. Like the early religions that our sudden linguistic evolution 70,000 years ago allowed us to conjure up, the concept of money became rapidly entrenched in our collective psyche. Today, a bank account’s number of zeroes—this digit an important invention of Indian origin in its own right—is the most reliable metric of a person’s social status, having a direct correlation with daily calorie intake, access to education and average life expectancy. There are only a few contemporary societies that don’t use a recognised currency, most of them isolated indigenous communities.

Unlike money, not all ultimately impactful inventions have such an immediate effect on society. Around 350 years after the introduction of Lydia’s currency, the Greek mathematician, philosopher and engineer Archimedes designed a threaded device for draining flooded land or irrigating areas affected by drought. Utilising a spiral thread encased in a hollow tube, the device could be wound by hand, wind or animal power. Although there is some debate as to whether the concept originated in Mesopotamia, it is Archimedes who is widely credited for refining the idea of a screw thread wrapped around a cylindrical or conical shaft for transforming axial motioninto linear motion. Little did he know how integral this technology would become over the next centuries.

Before engineers were ready to fully embrace the potential of the screw thread, first there would be two immensely pivotal technological developments, both with powerful yet very different sets of consequences. The accidental discovery of gunpowder by Chinese alchemists searching for an elixir of immortality in the ninth century created a potent formula for the shortening rather than the extension of human lives. Combining potassium nitrate, sulfur and charcoal to produce violent and sudden explosions, this black powder went on to transform global warfare, resulting in huge imbalances of power and extensive worldwide colonisation.

The printing press, although less violent in its means, had as great an impact on global affairs as gunpowder, if not more so. Prior to its invention, the only books that existed were handwritten or printed using woodblocks with intricately carved, mirrored scripts, and nearly all were copies of the Bible or other religious texts. In 1440, the original printing press was painstakingly created by Johannes Gutenberg. He first designed a font with uniform size and shape—an undertaking that in and of itself required great precision and forethought—with master letters individually carved, then cast in metal alloy. These letters were then arranged in the correct sequence inside a forme in order to print copies of one complete page, one after the other, in batches of hundreds for later assembly as complete books. Borrowing technology from the wine press, the printing press used a screw thread to exert steady and even force that would allow Gutenberg’s customised ink to adhere to his specially designed paper. Three years in the making, the first print run was completed around the year 1455—with 180 copies of the Bible of course, much to the delight of the Vatican. While this proof of concept may seem nauseatingly slow by today’s standards, it was revolutionary for its time and completely transformed the spread of information. What started with fewer than 200 books quickly led to millions by the year 1500. The printing press and the abundance of information it made accessible would help usher in the Age of Enlightenment, which began towards the end of the seventeenth century. Promoting reason, political philosophy and human rights over religious ideology, these principles provided the intellectual foundation for the coming Industrial Revolution, with innovators and inventors incorporating scientific principles into their work and benefitting from an ever-expanding collective bank of knowledge.

Industrial Inventions

One such innovator was John ‘Iron-Mad’ Wilkinson, whose obsession with the material didn’t end with his iron desk, iron boat, or preparatory iron coffin. In 1774, he developed a method for ensuring the trueness of British naval cannons, eradicating weak spots and making them much safer during discharge. The method involved casting solid cylinders—rather than those with a pre-moulded shaft that were prone to errors and blowouts—then boring a channel with a screw-driven borehead, yet another technological advancement to utilise the screw thread. So successful was this method, that his contemporary James Watt soon caught on, commissioning Wilkinson to cast several huge precision-engineered iron cylinders to solve the problem of leakages in his steam engines. Bored to a previously unheard-of tolerance of 0.1 inches, the iron cylinders snugly housed Watt’s pistons, dramatically increasing the efficiency of his engines, transforming them from machines suitable for draining waterlogged ditches—much like Archimedes’ screw—into powerhouses of the Industrial Revolution.

Building on the achievements of Watt and Wilkinson in the field of precision engineering, in 1797 Henry Maudslay developed the screw-cutting lathe with its innovative slide rest. Working as a locksmith for renowned engineer Joseph Bramah, Maudslay became known for his skills of precision and replication, creating custom machines to reproduce standardised components at scale. His lathe would come to be regarded as the mother tool of the Industrial Age by historians such as Joseph Wickham Roe for its ability to machine parts to a tolerance of 0.0001 inches and reproduce screws with consistent thread profiles and pitches. This technology became an integral part of the Industrial Revolution as a means of power transmission and precisely calibrating moving components.

Later, in the nineteenth century, the mass production techniques that Maudslay pioneered led to the development of interchangeable, mass-produced threaded screws, benefitting watchmakers and gunsmiths, who were previously required to carve these parts by hand. In the early twentieth century, Henry Phillips created the Phillips-head interface, a non-slip screwhead design that spared joiners and labourers the raw effort of hammering nails into timber. Today, standardised screws and bolts are the go-to fixing mechanism for most interfacing components, a precise technological innovation that has made its way under our skin, boring itself deeper and deeper to become part of the very flesh it once sought to spare from labour.

The period of industrial progress and precision engineering, to which Wilkinson, Watts and Maudslay contributed so much, represented human’s quest for complete dominion over nature. No longer would we yield to its whims, rather our existing machinery and ever-expanding intellect would strive to exploit its full potential, at least in the ‘developed world.’

History has a tendency, especially when looking at the period including the Industrial Revolution, to centre on the ‘developed world,’ with Britain at its nucleus. This Western gaze overlooks societies that lived—and still live—in harmony with nature. Then, as now, indigenous communities inhabited lands untouched by colonial conquest or corporate exploitation, developing and refining their own technology, but without a written record, they are unable and, in all probability, see little need to document who created what specific tools or processes.

Western concepts of record-keeping, patents and historical eras are absent in cultures like the Pirahã, an Amazonian society along the Maici River. Their language is without numbers, temporal tenses and verb conjugations, prioritising direct experiences and the present moment. A 2009 census estimated that only 250 to 300 Pirahã speakers remain, with most closely-related indigenous communities having already adopted Portuguese. For how much longer the Pirahã can resist the encroachment of ‘developed’ Brazilian culture remains to be seen, but for now they rely on their expertise in jungle survival, using mostly natural materials and a few useful Western tools like knives and machetes.

The use of outsider technology by remote communities may seem harmless, but Napoleon Chagnon’s controversially-titled book, Yanomamö: The Fierce People (1968), argues that the introduction of metal tools to an indigenous community of 200 to 250 villages located in the Venezuelan and Brazilian borderlands had devastating effects on their culture. The anthropologist claimed that the machete and axe intensified existing conflicts between villages. Prior to the arrival of these weapons, originally introduced by missionaries as tools for cooking and clearing forests, the Yanomamö relied on stone and wooden tools, which were more difficult to obtain and far less deadly. Violence is responsible for up to half of all male deaths amongst the Yanomamö people, but critics of Chagnon’s theory claim that spikes in bloodshed are more likely the result of economic, environmental and health-related pressures brought by non-indigenous people. Whatever the exact cause, it is clear that contact with the ‘developed world’ profoundly affected the functioning of Yanomamö society.

Based on such anecdotes, it is easy to jump to the conclusion that all introduced technology must therefore be harmful to indigenous communities used to living in harmony with their surroundings. However, the Oglala Lakota—one of the seven sub-tribes of the Lakota people—are a living example of how Western technology can be embraced and mastered. Before the arrival of European colonists in the eighteenth century, the Lakota relied on dogs to pull travois, a wheel-less sledge used for transporting goods. With the introduction of horses, likely through Spanish trade routes, they adapted quickly, revolutionising hunting, transportation and warfare andmarking a significant shift in their way of life. They soon became expert horse riders, breeders and trainers, their non-coercive training techniques allowing them to bond with their horses, rather than ‘break’ them. Additionally, several endemic inventions were developed by the Lakota—who nowadays mostly inhabit the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota—such as rawhide and sinew bridles, which negated the need for a bit, and buffalo-hide saddles, which were lightweight and designed for speed and agility.

That the sudden introduction of foreign devices or concepts can change a society so profoundly should come as no surprise, for what is technology without its capacity to modify human behaviour? Good intentions may be the foundation for our inventiveness, but we can never really know the side effects until they play out, at which point we are impelled to create new solutions to the incoming set of problems. It is an accepted truth, at least in capitalist societies, that humans must create their way out of trouble, solve problems by continually advancing technology. What would we make of our lives, if indeed, there were no barriers to overcome and facets of nature still to be tamed?

Modern-day Inventions

The nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw the rise, in rapid succession, of the electric telegraph, the telephone, the pager, the cellphone and the smartphone. These inventions facilitated human connection like never before, overcoming the barriers of mountains, continents and entire oceans. But the latest iterations of the ‘phone’ have us spending more and more of our waking hours looking at screens, dramatically reducing our attention spans in the process. Many of us are now searching for ways to protect ourselves and our children from overexposure—without losing connection to the outside world through complete abstinence from mobile phones and social media.

Even developments in audio playback have their downsides. The rapid twentieth-century transition from radio to records, cassette tapes, CDs, and MP3 files reduced the need to gather for entertainment, empowering musicians and permitting unparalleled access to artistic expression, thus shaping the popular culture that began emerging post-World War II. With the streaming age upon us, the consumer has never had more choice, but access is controlled by a few powerful corporations in the form of digital feudalism. Consumers must pay a monthly fee to stream music, yet artists receive only a tiny fraction of revenue, creating a trend of digital exploitation.

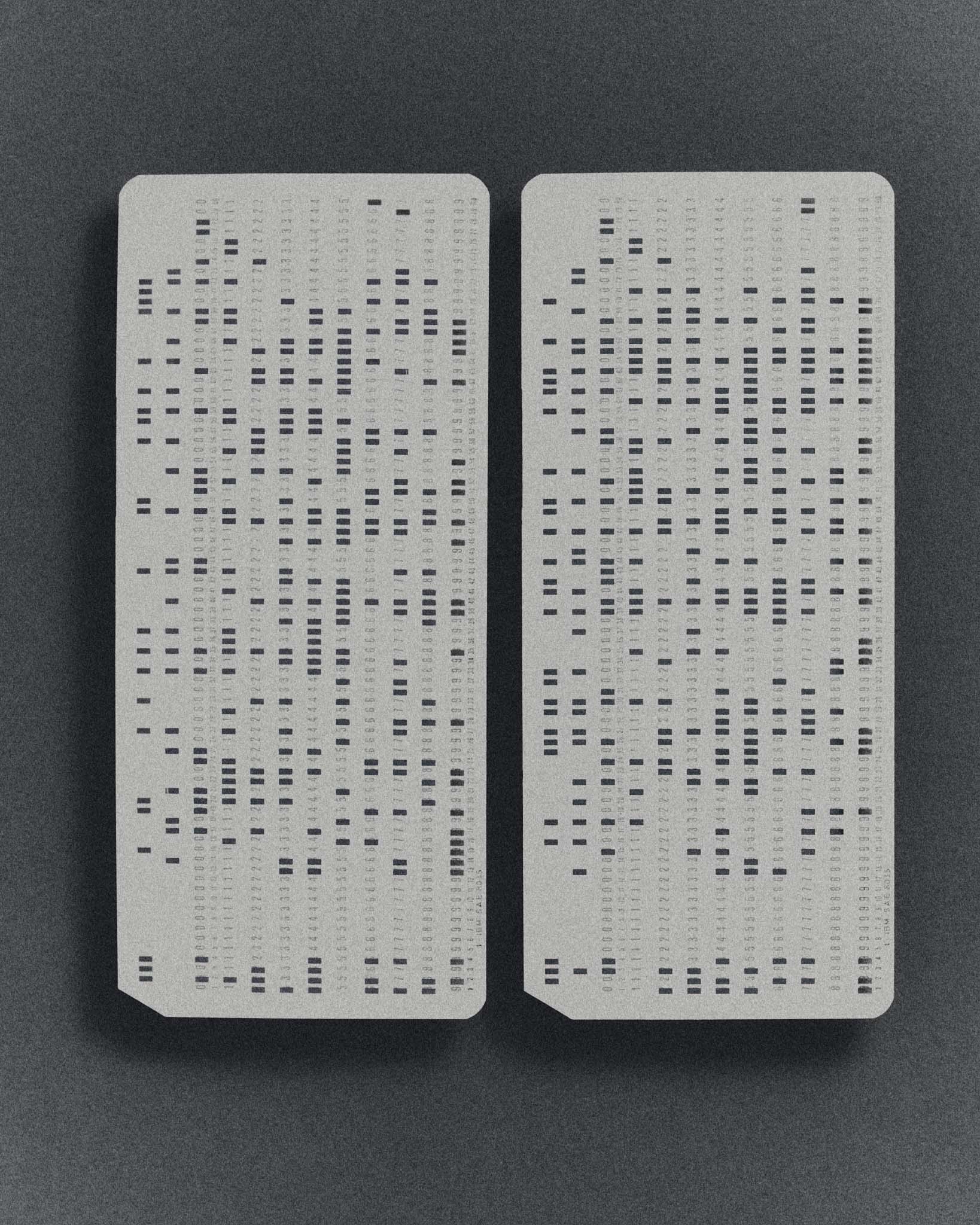

Radio and records may be the inventions that history remembers, but it is our addiction to streaming and scrolling that has become part of our human identity. Naturally, the huge developments in the way we entertain ourselves wouldn’t have been possible without advancements in electronics and computing. Since 1941, we have gone from electromechanical computers to fully electronic computers with the first silicone microchips in the span of just 17 years. Computing power has increased exponentially, giving rise to the internet and the eventual outsourcing of cognitive functions to external brains through AI language models—perhaps the obvious next step for a species whose inventiveness first hinged on its linguistic dynamism. Undergirding AI are the most powerful microchips ever created, with transistors half the size of a biological virus, carved using ultra-precise lasers. AI-pioneering nations like China and the United States now compete for access to these chips, the majority of which are produced in Taiwan, contributing towards global instability.

As we grapple with the dangers associated with AI—such as geopolitical rivalries and a recent case of self-replication—the field of AI ethics is emerging as a critical way to govern how these auto-didactic language models interact with humans, in particular looking at responsible use, bias, privacy, accountability and human well-being. There are already serious questions being raised around AI’s effect on the labour market, as well as moral concerns around its military applications.

AI has its advantages, of course. It was instrumental in the rapid development of the COVID-19 vaccine, analysing millions of compounds to identify potential vaccine components, and is also being used for cancer screening and to match new drugs with suitable candidates. Technology has always been closely intertwined with our desire for healthy living, from the development of simple stitches to bacteria-battling penicillin, bringing widespread benefits to the masses. There are a privileged few, however, who choose to spend their millions for personal gain, using powerful algorithms in pursuit of the most effective combinations of treatments and supplements for delaying biological aging. Former tech entrepreneur and willing longevity guinea-pig Bryan Johnson believes his commitment to the cause may eventually permit some humans to avoid death altogether. This raises important questions around access to healthcare and who benefits from advancements in technology.

If there is one problem that technology appears to be exacerbating rather than remedying, it is global inequality—with countless millions being funneled into the pocket of tech billionaires and the gap between the rich and the poor only growing. While cryptocurrencies may offer opportunities to a small minority through investment gains and blockchain-mining, critics like YouTuber and inequality campaigner Gary Stevenson are quick to compare even the most legitimate coins such as Bitcoin to valueless pyramid schemes. Environmental campaigners, on the other hand, may well point to recent studies that show up to 2.3% of the United States’ energy consumption—a largely fossil-fuelled economy—stems from Bitcoin mining.

As technology solves one problem, it almost always creates another, and as we become an increasingly technological species, at least in the ‘developed world,’ this cycle is occurring at a faster rate than ever before. But even if the drawbacks of AI and social media are clearly visible, we tend not to reject them as—at least on the surface—they appear to make life just that little bit easier. Not only is it difficult to see past the disadvantages of digital technologies, it’s also quite remarkable how quick we are to adopt them, readily inviting intrusive social media platforms, hackable smart speakers and AI chatbots with mysterious algorithms into our lives.

Whether we are aware of it or not, we are the technology we use. Our physical and digital tools have the power to fundamentally change our species, and will continue to do so at a faster rate than ever before. But what of the few remaining isolated communities that have little to no contact with the outside world. Are they also changing?

What, from our perspective, may seem like inertia is simply a slower rate of technological advancement, with the cultures of remote people changing at a similarly unremarkable yet more sustainable rate. It is a paradigm that stands at odds with that of the ‘developed world,’ where rapid progress has become a foregone conclusion. For modern technology possesses its own onward momentum, like the impossible perpetual motion machine its constant striving for efficiency gains seems intent on begetting.

Yet despite this contrast, our use of technology is still very much what makes both groups human. There may be a gulf between the types of materials used and the needs that technologies cater to, but the spirit of problem-solving and inventiveness of our ancestors resonates today through our shared seeking of the path of least resistance. This may manifest as the adoption of equine culture by Native American communities, the acquisition of steel tools by modern Amazonian tribes, or the widespread acceptance of potentially dangerous AI by Western societies. No matter whether its origins lie in the jungle or the ‘developed world,’ it still constitutes the adoption of new technology.

Like the screw thread, our critical faculties and creative nature are tasked with sparing us effort, constantly turning, like clockwork, driving us forwards as efficiently as possible, and underpinning our intellectual evolution as we go. Super–powered by our ability to abstract through language, together humans can dream up solutions—and problems—of immense complexity, visualised through the power of our insatiable imaginations. Expending precious calories in search of inspiration for new efficiency gains, we employ our massive brains and the technologies already at our disposal to aid further technological development, constantly building on the foundations already laid by those who have trodden the Earth before us, and for the benefit of those yet to tread. For better or worse, ours is an inventiveness that truly knows no bounds.