Few have visited the number of home interiors that François Halard has, though it is likely that many of us have seen images of so many home interiors because of him. As an acclaimed interior and architectural photographer for over forty years, Halard has worked with magazines from decoration international to World of Interiors. His first proper gig was a cover for the French interior decoration magazine, Marie Claire Maison, while still a student at the École Nationales des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. By the mid-1980s, when Halard was 25, he was asked by Alex Lieberman, the editorial director of Condé Nast, to work on its publications, beginning a decades-long collaboration with the likes of Vogue, House & Garden, Vanity Fair and GQ

While much of his work with magazine clients has the gloss and sheen that is to be expected of interior publications, Halard has also cultivated a more honest style of interior photography that has been the focus of a series of books, published by Rizzoli. The eponymous series, first released in 2013, with the final component released ten years later, offers an intimate look at the homes of artists, architects and designers such as Yves Saint Laurent, Carlo Mollino, Miquel Barceló, and Louise Bourgeois, captured from the perspective of the photographer himself.

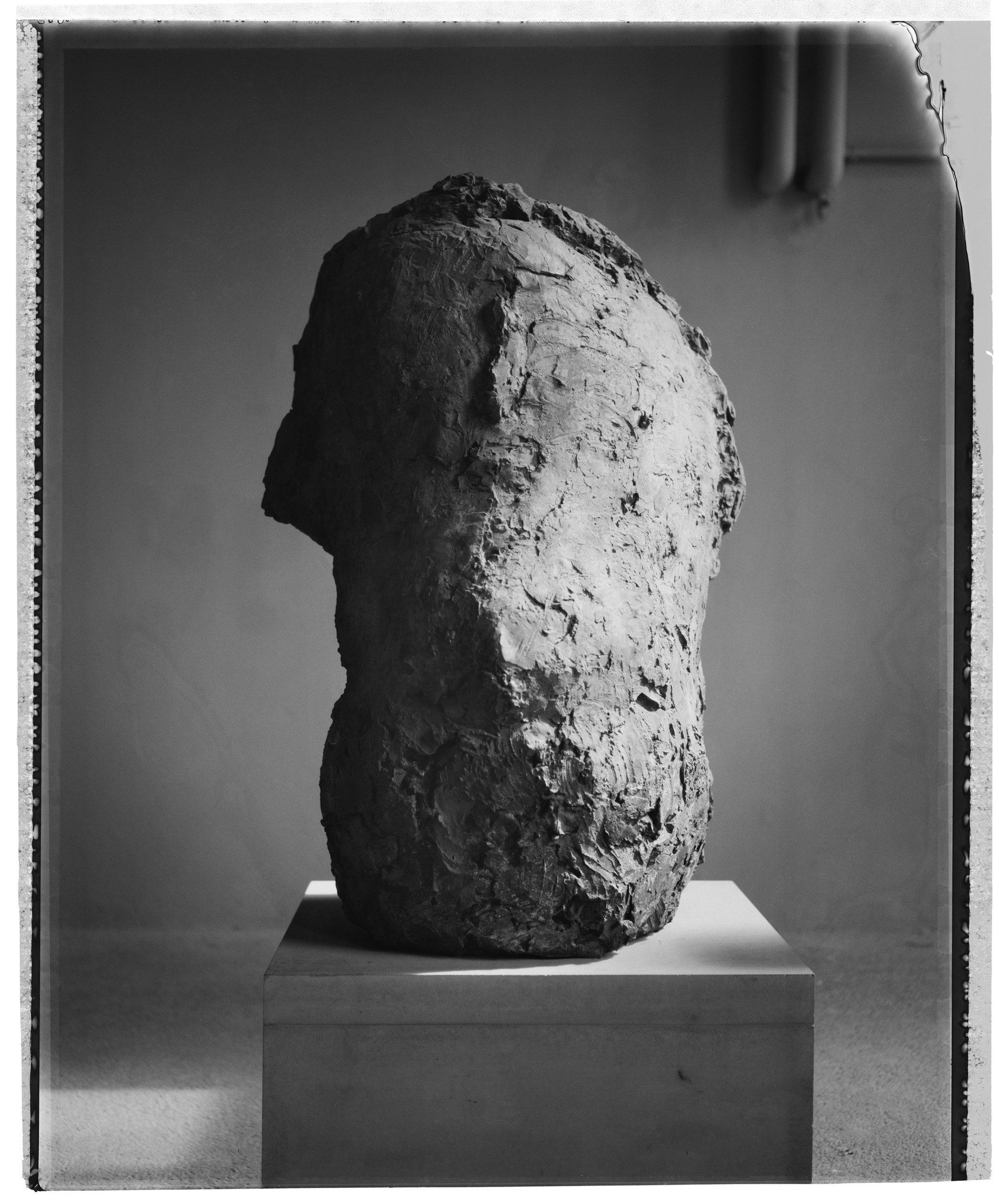

The latest book, Francois Halard: New Vision marks a shift in approach from the first two, however. As he explains over the phone to Present Space, “the new book is more personal, it’s more about freedom.” The focus is less on grand shots of beautiful interiors, and more about documenting the experiences that Halard has had visiting the homes and art studios of those he admires—experiences that have resonated with him, and which he cherishes. In this way, it’s an autobiographical journey into the memories Halard has made over an extensive career. The artist Cy Twombly, for example, features heavily in New Vision, and is someone whom Halard has long been inspired by (Twombly’s home features in the first instalment of the series, where Halard describes the artist as his hero).

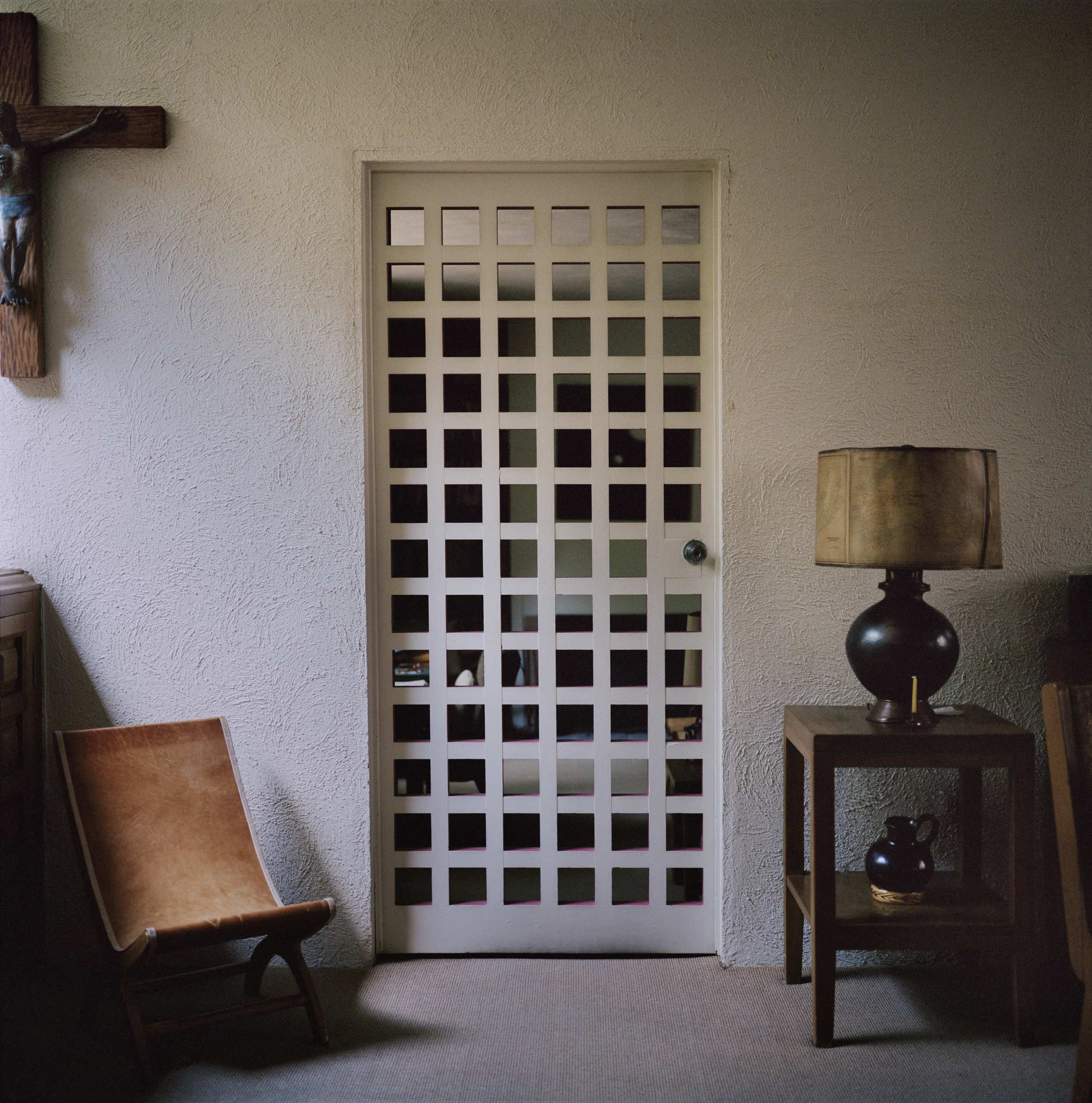

What this intimate book series captures is the deep connections that the photographer has forged with the spaces he has visited over time. This is evident as the series progresses, as the books increasingly take on the feel of a personal scrapbook (the second instalment is subtitled A Visual Diary), in which Halard’s brushstroke-like handwriting is combined with close-up details of the inhabitant’s belongings. More recently, Halard has turned to using his distinctive handwriting as part of a more artistic exploration yet, combining painting with the glossy photographs he is so accustomed to taking. The result is an increasingly personal investigation into how stuff—objects, paintings, furniture, surfaces—create the spirit of a place, behind the sheen of the stylised interior.

I got into photography at a very early age because I was quite shy and reclusive, and my only communication with the external world was through magazines and books. My parents were interior designers and there were many times when photographers would come to the house to photograph it. When that happened, I would usually skip school to watch them working, to see how they take a different approach to the space and express it in a certain style. I remember Helmut Newton coming to my parents to photograph it, there were many key photographers of the generation that visited. I was quite intrigued by the influence, or the power, that the little box [of the camera] can give you because it’s a way of exploring something different. It’s also a way of protecting yourself from the outside world. I think that relationship is very important.

Yes, I think what I’m trying to do is be a mirror of that person or artist, to do justice to the place and the owner. I’m trying to capture the ghost of the image: the ghost living in that space. I try to be as little documentaire as possible because I’m not really interested in showing the space. I’m more interested in revealing the space. So, for me, it’s much more personal. That’s why I think it’s very important to make books because you can have a much more profound experience than just looking at pictures via Instagram. It’s another feeling. And I love the feeling of books. I’m a big book collector; I love the smell of the paper, and I like the fact that you need to take time to go through them.

It was quite challenging to take my work in a more artistic direction and to be more personal. It’s more or less about photographing beauty, and what beauty is for me. It could be an object, it could be a painting, it could be a light, it could be something much more abstract. Sometimes I think by focusing on details, you give more feeling than showing the entire space of a room.

Yes, exactly. The pages of the book are like collecting my memories. I think it’s very autobiographical. I can show, without constraints, what I really like to photograph, what I really like to show—it’s much freer and more liberated in a way. I made New Vision with my friend, the art director Beda Achermann. We’ve known and collaborated together for a long time, and I think it’s nice to always have somebody you work very well with, trying to push you to go an extra step towards something personal.

The key is not to think about it, because if you think about it, you’ll freeze and get really anxious: “I have only one hour!” If you go there with that in mind, you are overwhelmed because you don’t know what to do. And so, my process is very natural. I go with the flow; I try to be intuitive. With the artist Cy Twombly, I’d been dreaming of visiting his home since I first saw pictures of it, maybe 40 years ago. Or, when I photographed Isamu Noguchi’s studio in Japan, I’d dreamed for many, many years of going there and feeling what it’s like to be in that place. So sometimes, that’s quite personal because there are a few pictures where I really did wait to be there and connect with somewhere I had already dreamed of.

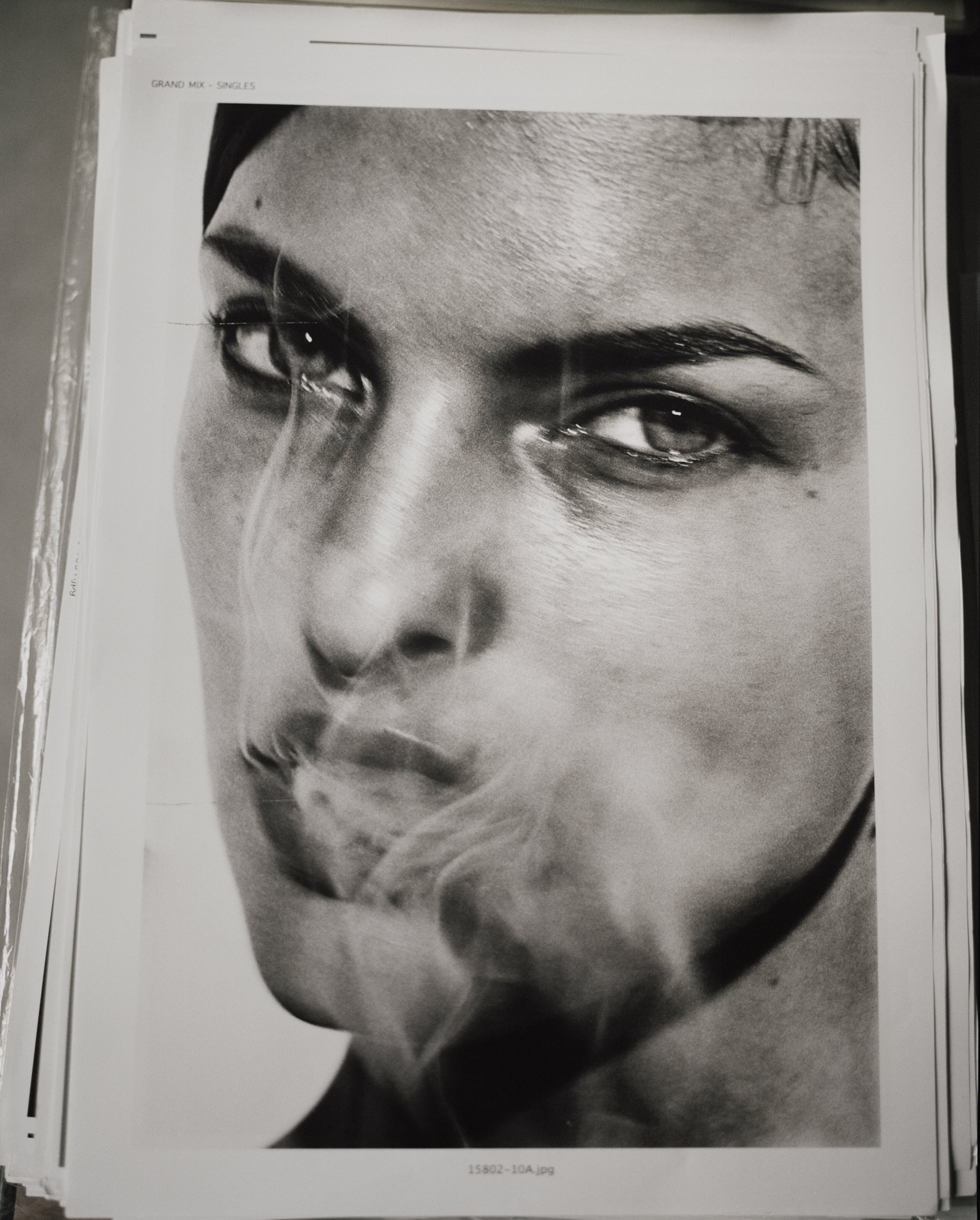

Yes, and this changed when I spent lockdown at home. I did a book about it called 56 Days in Arles, with my friend the curator Oscar Humphries, published by Libraryman. I took a Polaroid every day, and it forced me to use my own house as an art studio. It became a space for experimentation because I had the time to work on it. I could photograph everything I wanted, the way I wanted, without any commitments. I felt free to use my environment as the basis of a new body of work. Now, I’m doing big prints and reappropriating my work by adding painterly gestures, so it’s somewhere between photography and painting. That’s something I always wanted to do but never had time for.

All the places [I’ve visited] exist in my memory. It’s like building a library of images. And sometimes you say, “I haven’t seen this book for a long time” or, “I don’t remember this image,” and you go back to it. I have kept all the images I’ve made since I was fifteen…

Yes, people take care of the archive every day! In a way, how I photograph

Home means almost everything. A place where you can reconnect with yourself, a place that will inspire you, and at the same time, protection. It’s always that duality for me that’s very important, and it’s been important since my childhood. It’s a living memory. To me, my house is like living in a painting in three dimensions.