Origin, creation, birth, beginning—these are words we use daily in many different contexts and situations. However, upon hearing or seeing the word genesis, we immediately evoke other resonances and meanings, especially those of us immersed in the Western tradition to varying degrees. One of the most immediate references is the sacred text for Christians and Jews. It is the first book of the Bible or Torah, offering an account of the creation of the world, humanity and our ancestors, and narrating how the relationship between humanity and its Creator was established.

In Ancient America, there were no sacred books as such, but oral traditions recounting creation stories were and still remain essential to its Indigenous peoples. In the case of Mexico, some codices that were produced before the Conquest survive. A form of text recorded in pictographs using an ideographic system, some of these codices narrate stories or myths of creation. For the peoples who created them, they may have been considered sacred writings or paintings, although their use was closely linked to oral storytelling.

This writing tradition was not broken by the Conquest, as what are known as colonial lienzos (painted cloths) were subsequently produced, incorporating within them varying degrees of European influence. Additionally, there are texts in Indigenous languages written using the Latin alphabet, as well as texts in Spanish. Composed during colonial times, these contain multiple references to Indigenous creation stories. Furthermore, there are accounts and myths collected through anthropological studies, conducted during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries across Mexico’s diverse Indigenous communities, in which traces of these pre-Hispanic traditions can still be found.

Darkness, chaos, fire, creator gods, sacrifice, transgression—these words take on special connotations when linked to American genesis stories, specifically to the creation stories of Mexico. Immediately, we envision a succession of events, and time begins to flow. However, at the beginning, time did not exist; it did not pass. It was an inconsequential existence, a sort of eternity, a primordial time. Then, the time of creation occurred—terrible and transformative. A series of episodes and events unfolded, culminating in the age of humans, the time in which we now live[1]. In Mexican creation stories, as in those from other parts of the world, these three times can be distinguished, each with its own particular characteristics. Interestingly, these times closely resemble the three stages identified in anthropology for rites of passage within human societies, where the individual undergoes a drastic change in social status and identity within the group, resembling a new birth, just as the birth of the world.

For many Indigenous American peoples, the Conquest represented another cycle of genesis—so immense were the changes that it reshaped and disrupted their origin stories. In these narratives, God, Jesus and Mary became creator beings, merging with the events and characters of ancient, pre-Hispanic stories. In many communities, the Sun was named God the Father or identified as Jesus[2].

It is important to note that, in Ancient Mexico, there was a great cultural tradition shared by many peoples from the south-south east, centre, west, east, and parts of the north, known collectively as Mesoamerica. However, many areas in the north of the country never sustained peoples belonging to this tradition. In these regions, various northern traditions existed and still exist[3]. Nevertheless, interactions amongst these peoples were and continue to be constant and ongoing, leading to influences spreading in all directions over millennia. Despite this, the distinct characteristics of these two traditions can still be observed, as discussed henceforth.

Darkness, chaos, a soft, damp, completely flat land surrounded by a primordial sea—in which an amorphous aquatic monster lived—where gods wandered aimlessly and time did not yet exist. This was the beginning, according to the stories of the peoples of Mexico, an eternity without transcendence, yet containing the ultimate principle that gives rise to all existence: a supreme god, the father of all gods.

Ometeotl, the god of duality, was revered by the Nahuas of Central Mexico (including the Mexicas). This primordial, androgynous and creative being synthesised both masculine and feminine principles[4]. In one of the pre-Hispanic codices, the Codex Borgia, he is depicted as a warrior dressed in a skirt and other feminine garments as well as shown in a birthing position, giving birth to a child symbolised by a jade bead[5]. It is an interesting conception and representation from an ancient tradition that can offer important lessons to contemporary thought about how we perceive life, the sacred beings we believe in, people, genders, societal roles and identities. One wonders what would happen if someone today depicted the Christian God, the principle of all things, omniscient and omnipotent, dressed as a woman in a birthing position to illustrate an allegory of creation.

In Mesoamerica, it was believed that this primordial god of duality also had a female counterpart, forming a supreme couple. The parents of all gods, it was through their children that this divine pair played a role in the various cosmic ages of creation until reaching the present era, the age of humans. In many other Ancient Mesoamerican representations, this primordial god is depicted as an elderly deity, the god of fire, also regarded as both the father and mother of all gods. At the Cuicuilco site in Central Mexico, the oldest known representations of this god have been found, dating back more than 2000 years[6].

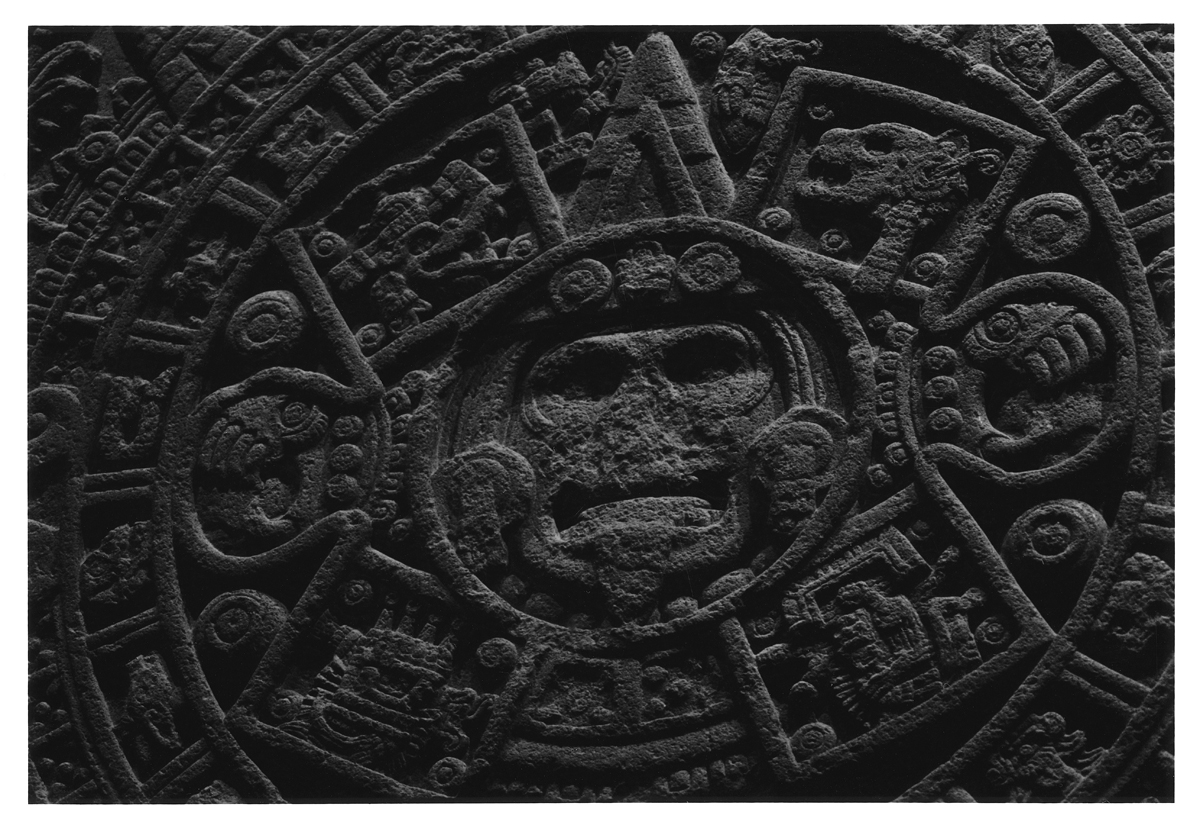

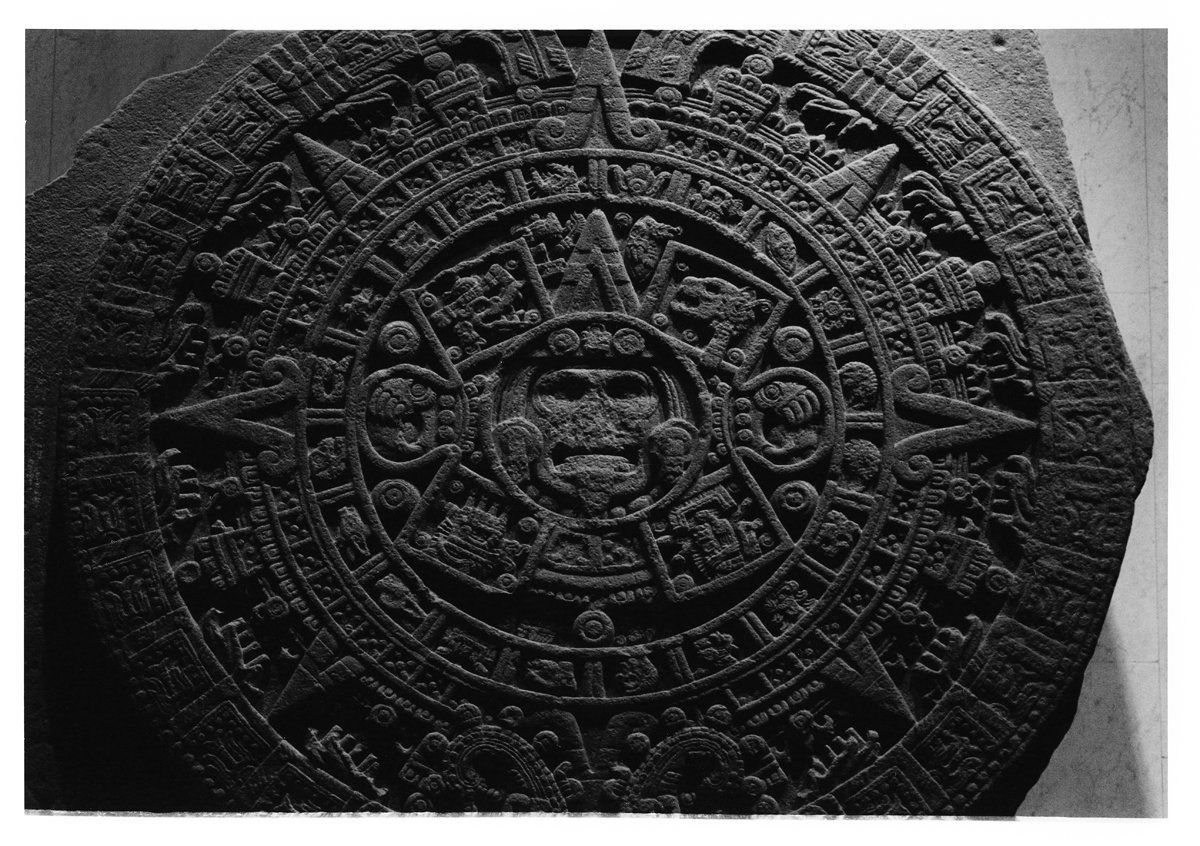

The ultimate principle or the supreme couple begins to act—having children, the ancestral gods—and so the great adventure, the period of creation, begins. In almost all narratives, multiple genesis events occur, with several worlds being destroyed and new ones attempted. Perhaps the most famous story is The Legend of the Suns from the Nahuas of Central Mexico, in which four suns are successively created, each ruling over a world with unique characteristics and humans made from different elements. Each of these worlds is then destroyed along with its dominant sun, making way for the next, until the emergence of the Fifth Sun—the era in which humanity originates, the age of man. It is a process of divine trials and errors, out of which humans are finally born. One of the most famous representations of this legend is the famous Sun Stone.

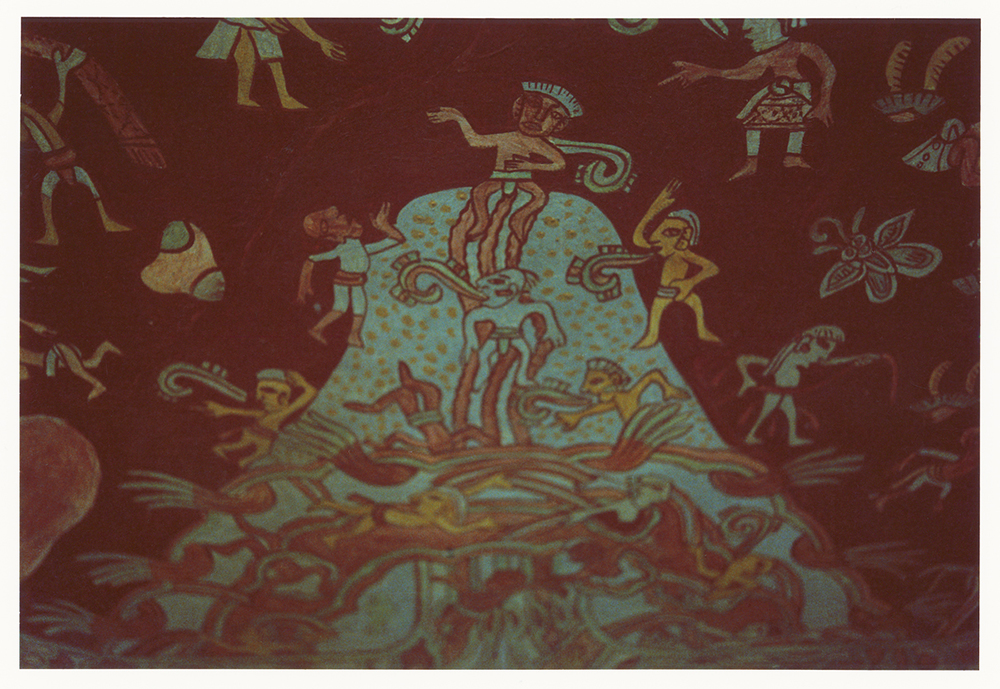

During this dramatic period of creation, fire and sacrifice play a crucial role. The ancestral gods must sacrifice themselves by throwing themselves into the fire to bring forth the new era and be reborn as elements that will generate the New World. Fire is the force that drives transformation at the moment of creation; sacrifice through fire is the sine qua non condition for resurrection[7]. For this reason, the fire god is considered the primordial god. Thus, to create the Fifth Sun, the gods throw themselves into the fire, with the first amongst them, Nanahuatzin, becoming Tonatiuh (the current Sun).

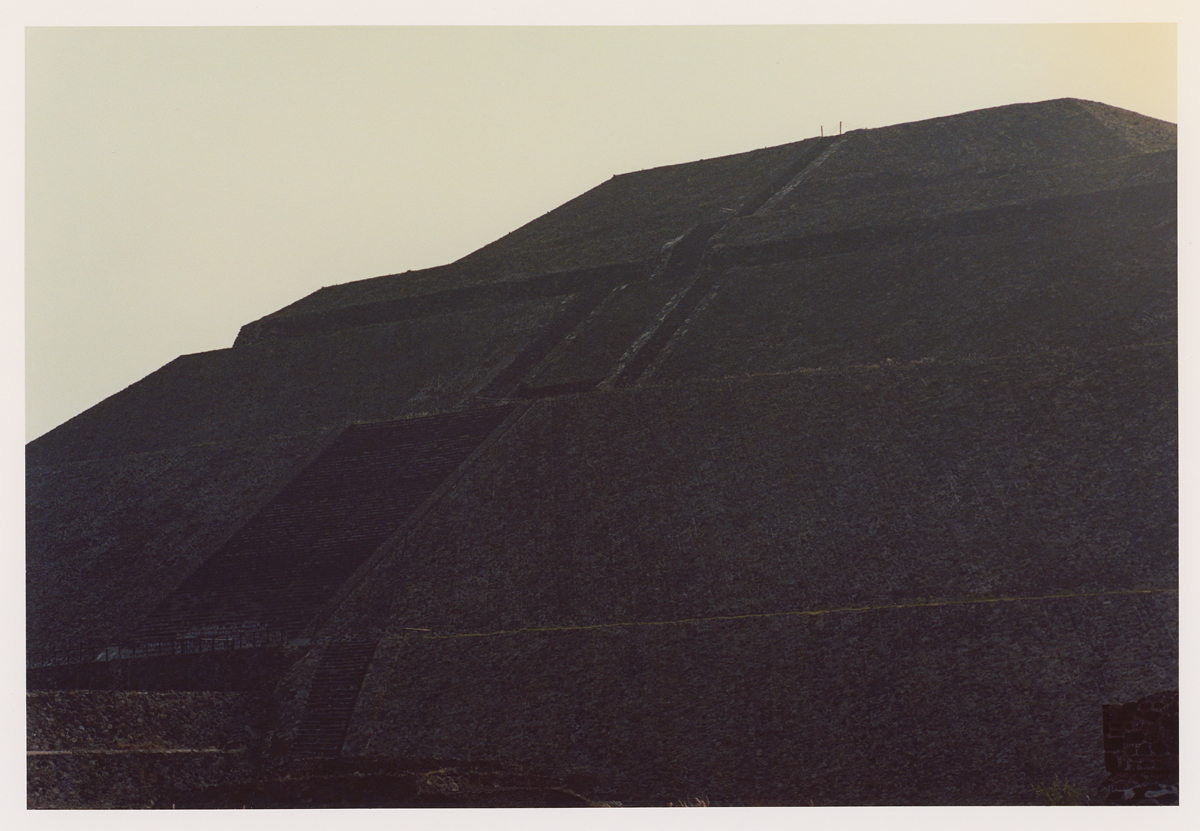

In the creation stories and oral traditions of these Mexican peoples, places of origin hold special significance. For the Nahuas and Mexicas in the final pre-Hispanic period before the arrival of the Spanish, the place where the gods threw themselves into the fire to create the Fifth Sun in The Legend of the Suns was the city of Teotihuacan. The Mexicas were familiar with the ruins of this city, which had flourished 700 years earlier in Central Mexico, and considered it to be a sacred place of origin, leaving offerings and placing the birth of the era in which they lived at this location.

In the oral traditions of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, there are often multiple stories explaining the creation of the world in different ways or focusing on different aspects or stages of this creation process, developing them in greater or lesser detail. In all of these origin mythologies, the creation of humanity is one of the central themes and essential purposes of the story. Many times, they are simply different episodes of the same grand story.

In another myth, also from the Nahua tradition, the gods Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca, two brothers who acted together but also fought, are responsible for both the creation and destruction of the world. At the beginning, they create the world. To do so, they tear apart and separate the body of Cipactli, the primordial aquatic monster, into two halves—one forming the Earth and the other the sky. After several trials and challenges, Quetzalcoatl is the one who ultimately creates humanity[8], descending into the Underworld, the realm of the dead, to steal the bones of one of the previous human races, created in earlier eras under the previous sun, in order to create humankind. Following many mishaps, he obtains the bones, emerges from the Underworld and gives them to the goddess Cihuacoatl. She grinds the bones on a metate (a traditional grinding stone), linking this act of creation to the process of preparing maize. Quetzalcoatl then performs an act of self-sacrifice, piercing his own penis to add drops of his blood into the mixture. With this, Cihuacoatl creates human beings[9].

In another myth, also from the Nahua tradition, the gods Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca, two brothers who acted together but also fought, are responsible for both the creation and destruction of the world. At the beginning, they create the world. To do so, they tear apart and separate the body of Cipactli, the primordial aquatic monster, into two halves—one forming the Earth and the other the sky. After several trials and challenges, Quetzalcoatl is the one who ultimately creates humanity[8], descending into the Underworld, the realm of the dead, to steal the bones of one of the previous human races, created in earlier eras under the previous sun, in order to create humankind. Following many mishaps, he obtains the bones, emerges from the Underworld and gives them to the goddess Cihuacoatl. She grinds the bones on a metate (a traditional grinding stone), linking this act of creation to the process of preparing maize. Quetzalcoatl then performs an act of self-sacrifice, piercing his own penis to add drops of his blood into the mixture. With this, Cihuacoatl creates human beings[9].

In many of these origin stories, even in different episodes of the same tale, death and resurrection play an important role in the genesis of those who will inhabit the New World. As previously mentioned, the elements of fire and sacrifice are essential. Quetzalcoatl’s descent into the Underworld in search of the bones and his subsequent return seem to symbolise his own death and resurrection, necessary transitions for creation.

In other Mesoamerican traditions, the creation of humanity is different. Amongst the K’iche’ Maya, the gods shaped humans out of maize dough. Although these might initially seem like different creation stories, it is important to note that, in the Nahua language, the word for maize translates to ‘our flesh.’ Amongst the Mixtecs, humans originated from a sacred tree located in what is now the Apoala Valley. One of the gods ordered a cut to be made in the tree from which men and women emerged, ancestors of the lineages that would later rule the Mixtec cities[10].

The Cosmic Tree, the axis of the world and the place of human creation in several Mesoamerican traditions, has its roots in ancient times. At the site of Izapa, Chiapas, a stela over 2000 years old depicts the Great Cosmic Tree with the divine creator couple on either side. In Palenque, on the Tablet of the Foliated Cross, which dates back to the Classic period, maize is represented as the axis of the world[11].

Up to this point, the creation of beings, gods, elements of the world, and spaces—such as the New Earth that emerged from the dismemberment of the primordial aquatic monster—and even places of origin have been discussed. However, as mentioned, it was only when creation was unleashed that time began to flow.

Time itself was also created, because in the primordial world of inconsequential existence, time did not yet exist. Thus, the creation of time occurs simultaneously with the rest of creation, as the act of creation necessarily takes place within time and unfolds through it[12]. In Mesoamerican traditions, the division of time was also created simultaneously—the Sun dies each night and is reborn every dawn—along with its measurement through calendars, especially the sacred count. In one of the Mixtec codices, it is observed that the first event in creation was the alignment of the 20-day signs of the ritual calendar. Time, and its orderly progression, are the first things to be created, paving the way for the rest of genesis[13].

The colonial Maya referred to the entire process of world creation as ‘the closing of time.’ The beings created during this process were marked by the day of their creation, which determined whether their destinies would be favourable, unfortunate or neutral. For this reason, in pre-Hispanic times people had multiple names, one of the most important—according to pre-Hispanic codices—being the day of their birth in the ritual calendar. This calendar was closely linked to space and the newly created Universe, corresponding to the different realms in which the sky and Underworld were divided: nine celestial levels and nine levels of the world of the dead, making up the 18 months of the solar calendar. Within it, space was infused with time, which carries destinies.

Amongst the northern peoples who did not belong to the Mesoamerican tradition, creation stories were and remain just as important and rich, although they were not as extensively documented as in Mesoamerica. However, analysis of the available information on these narratives reveals many structural similarities, suggesting interactions between these peoples over millennia. These exchanges fostered a shared foundation that later evolved in different directions. Some notable similarities include: a primordial time of darkness and chaos, a supreme god associated with the Sun, dual divine entities with both masculine and feminine aspects, the significance of fire and sacrifice in the transformative process of creation, multiple creations and successive destructions leading to the current world and humanity, and the importance of a great flood just before the creation of humans in our present era[14].

One of the most well-known episodes about the immaculate conception of beings, which in the Nahua tradition is closely related to the creation of the Sun and the Moon, is the myth of Coatlicue. This goddess picks up a feather that falls from the sky and places it against her bosom, becoming pregnant and giving birth to an extraordinary being, the god Huitzilopochtli. This story has parallels in northern traditions[15].

In versions of creation stories from the Tepiman language family, including the Pima and Tepehuan peoples, a young woman becomes pregnant after hiding a ball from one of these communities’ traditional games in her clothing, giving birth to a girl with claws ‘like a bear.’ There are also similarities between the story of Quetzalcoatl and that of I’itoi, a cultural hero from this tradition.

When referring to the creation myths of these northern peoples, the first word that comes to mind is ‘emergence.’ In these traditions, one of the fundamental episodes is when humans, or the ancestors of the lineages that will populate the world, emerge from the Underworld through holes or openings in the Earth’s crust. These places become highly sacred and are considered the symbolic navel of the Earth. In some communities, this navel-hole is called sipapú and each lineage identifies with the place where its emergence occurred. Thus, creation and emergence are closely related.

Other differences between northern and Mesoamerican traditions can be seen in the different order in which various mythological episodes or mythemes appear within the overall structure of their stories, despite sharing similarities.

One final distinction relates to animals and the different roles they play in these creation myths. One of the most notable examples is The Theft of Fire myth, which is carried out by the marsupial tlacuache (opossum) in Mesoamerican tradition, while in some northern traditions, it is the roadrunner or chaparral bird that plays this role[16].

The significance of these creation stories and their characters in our modern world can be surprising. For example, Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner, one of the most popular children’s animated series created in the United States, is inspired by these figures from the oral traditions of the Indigenous peoples of Northern Mexico and the Southwestern United States.

In all of these narratives, one of the most important messages is that everything is cyclical, nothing is eternal. Even in Nahua tradition, it is written how the Fifth Sun, the era in which we live, will eventually end. It is not a genesis meant to last forever; many more cycles of creation will follow. However, if the pact between humans and the creator gods who sacrificed themselves to bring the world and humanity into existence is honoured, and if their essence and presence in the surrounding environment are respected, then the Sun that warms us and gives us life will continue to rise each morning.

The key is to respect all of creation—everything that in Western thought is seen as mere nature, lifeless and without consciousness, but that in Indigenous traditions is believed to have a soul, a perspective, and the ability to act. Perhaps the lesson is to establish a different kind of dialogue with our environment so that we do not bring about the death of the genesis in which we live.