My eyes burn from the tears streaming down my face. I’m filled with an overwhelming sense of grief. In one hand, I’m holding on tightly to a sharp pair of scissors, whilst in the other there is a generous handful of freshly chopped brown hair. I had meticulously planned and rehearsed this moment for weeks, but this intense emotional reaction I’m now experiencing—especially in front of thousands of people—was certainly not part of the plan.

Where did this rush of tearful emotions come from?

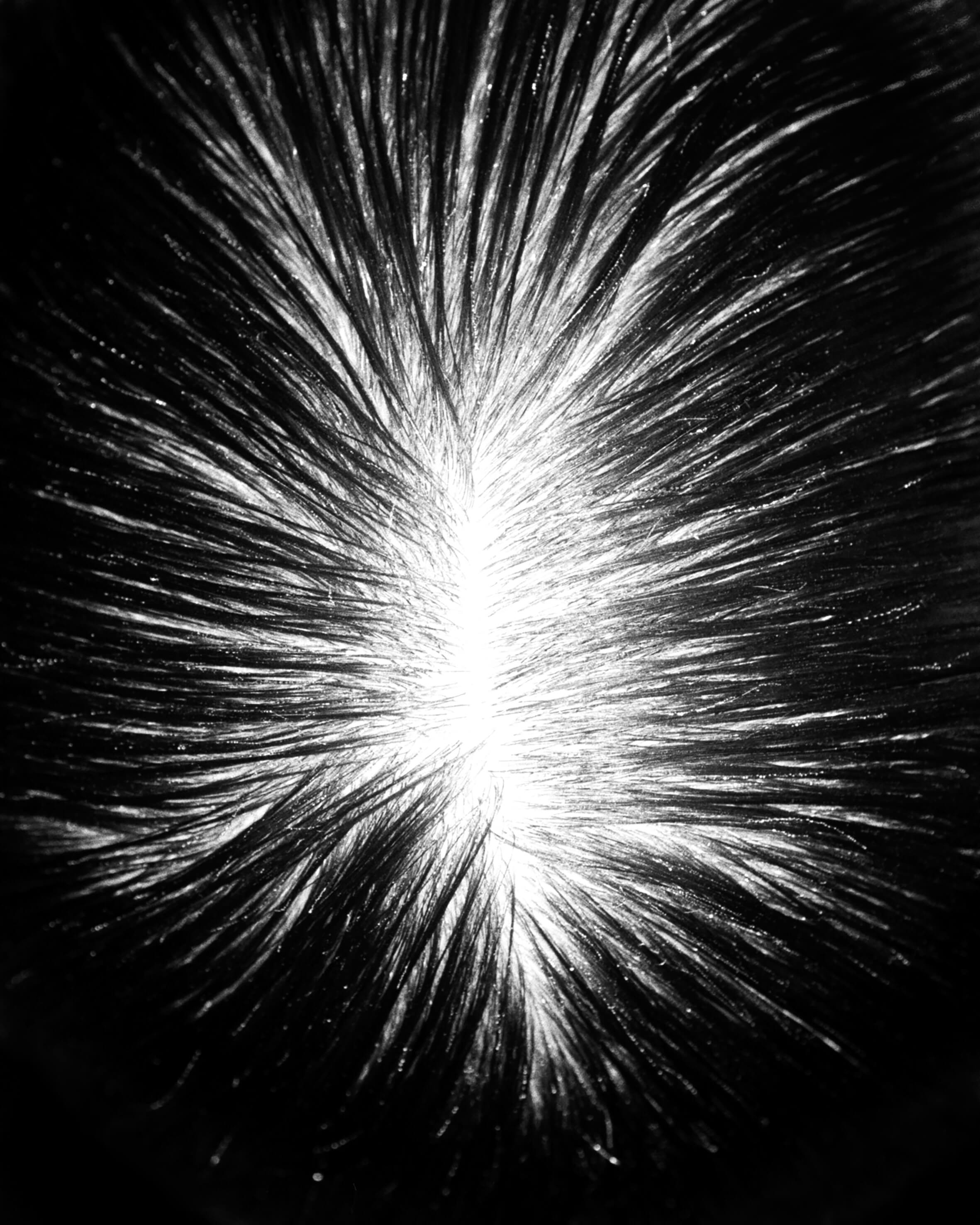

This was the most daunting aspect of a TED Talk I gave last ear in February 2023, at London’s Sadler Wells theatre, which was out the nationwide anti-regime protests that had taken over my birth country of Iran. Cutting one’s hair, especially for women, had become a visual symbol of call for an end to the clerical rule of the Iranian regime. In support of the movement, and as a symbolic gesture of solidarity with those bravely fighting against tyranny, I decided to cut my hair too as part of my presentation. What I hadn’t realised at the time was the profound significance of the ritual I was participating in, across the world and throughout history.

Hair is largely regarded as a symbol of life amongst many cultures, and the act of cutting it tends to transform personal and communal experiences into visual acts of loss, sacrifice, devotion, detachment, and change. For some Native American tribes, like the Choctaw and Navajo people, cutting hair during mourning signifies severing ties with the deceased, and its regrowth symbolising new beginnings. In Hindu traditions, shaving the head after a loved one’s death represents detachment from worldly attachments, while cutting hair is used to symbolically honour the dead and mark a new life stage in some African cultures. Similarly, in some Buddhist practices, a shaved head signifies renunciation of material life and spiritual enlightenment. Historically, Japanese samurai cut their topknots to signal major life shifts, such as retiring from warrior status.

This ritual has particularly deep roots in the culture and history of the region in which I was born and raised: Iran. In Farsi, the practice is referred to as “Gisuboran”: “Gisu” translates to “hair”, “boran” to “cutting,” and it is, as with the other examples cited, particularly intertwined with mourning rituals. The oldest known record of Gisuboran in the region is found in the Epic of Gilgamesh, a 3500-year-old poem from ancient Mesopotamia. One of the world’s oldest known works of literature, it depicts the mythological king Gilgamesh cutting his own hair in mourning for the death of his close friend Enkidu. “I will order everyone in the land to cry and cut their hair for you,” King Gilgamesh is quoted, “and I will grow my hair back in your honour.”

In Zoroastrianism—the dominant religion in pre-Islamic Persia—Gisuboran was a significant ritual performed during periods of mourning. A visible manifestation of grief and a communal expression of sorrow, the act symbolised the severing of ties with the deceased and the acceptance of life’s impermanence, a way to soothe the pain of the loss.

Over the centuries, Gisuboran retained its symbolism, most evidently within Persian literature. One of the most renowned references is in the Shahnameh, a pivotal work in Persian literature written 1000 years ago by the 10th-century poet Ferdowsi. Also known as “the Book of Kings,” it’s an epic poem narrating the mythical and historical past of Persia, credited with reflecting and safeguarding its cultural heritage, language, and identity. The most notable reference to Gisuboran in Shahnameh is when Farangis, a beautiful princess, cuts her long black hair upon discovering that the enemies of Iran have murdered her beloved husband and the legendary hero of the book, Prince Siavash. The bereaved princess is depicted wrapping her severed locks around her waist, announcing her abstinence from that moment on—a symbolic gest re to demonstrate her refusal to pursue a normal life; that things will never be the same again.

The ritual is so deeply embedded in the culture that it has been reflected similarly in other noteworthy works of literature by eminent Persian poets and writers, including Hafez, Khaghani, and Salman Savaji, in reference to mourning and objection to injustice.

A particularly vivid depiction of Gisuboran that caught my imagination is a scene from a book called Savushun by Simin Daneshvar. Published in 1969, it was the first ever Persian novel written by a woman, and it tells the story of the British occupation of Southern Iran during the Second World War from the point of view of an obedient housewife named Zari, who transforms into a vocal defender of her husband’s cause after he is killed. In the novel, Daneshvar writes about Zari’s internal dialogue upon coming across a “Gisu Tree”:

“When I first set eyes on the Gisu Tree, I thought it was a wis tree; a shrine embellished with colourful offerings from devot es. But when I got closer, I saw its branches adorned with severed locks, once belonging to women who had lost a beloved man; a husband, a son, a father, or a brother.”

Many believe such trees have, and do, exist, though I have not found solid evidence to support the claim. However, the ancient ritual of Gisuboran is still observed today among certain ethnic communities in parts of rural Iran. The practice is particularly prevalent among the Bakhtiari people, a large ethnic group mostly residing in the southwest of the country. During funerals, Bakhtiari women close to the deceased cut their hair in mourning. Some trample on their severed locks, while others leave them on the grave or bury them with the deceased.

Another Iranian ethnic group among whom Gisuboran is still prevalent are the Kurdish people, who mostly reside in western Iran. During traditional Kurdish funerals, close female relatives of the deceased cut their hair, hanging their tresses around the neck of a horse carrying the body of the deceased while chanting sombre melodies in a procession to the cemetery. The practice is also observed in parts of central Iran, where women hang their hair on the headstone of their loved ones, a reminder of the silent mourning that continues as the strands of hair dance in the wind.

Though Gisuboran as observed in our history and literature had almost faded away among most Iranians, especially those living in cities, recent events have brought this ancient practice to the forefront.

In September 2022, 22-year-old Mahsa Jina Amini died in custody after she was arrested for showing more hair in public than was deemed acceptable by the so-called “morality police”, the ever-present big brother figure tasked with making sure that the state’s interpretation of Islamic law is being reinforced. What followed was months of widespread anti-regime protests across the country, led by women fed up with decades of misogynistic oppression and discrimination. They were supported by a nation of people outraged by corruption, religious chauvinism, and sparse civil rights. Known as the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, it became the biggest threat to the existence of the authoritarian rule of the Iranian regime since its formation in 1979. The government responded with a brutal and bloody crackdown. Over 500 people were killed, around 70 of whom were children. Thousands were arrested, and many were later executed.

Then, spontaneously, and as part of the protests, many started cutting their hair. As if exhuming the ancient tradition, Iranians publicly expressed their grief for the lives unjustly taken, their objection and detachment from a system and people that caused it, and their battle against injustice and fight for change.

One of the most iconic images of this time was of Roya Piraee, who, with a shaved head, stood by the grave of her mother Minee Majidi, who was killed in the protests. As Farangis had done in Shahnameh, the grieving daughter cut her hair to mourn, symbolising that things will never be the same again. Another powerful image was that of the sister of Javad Heidari cutting her hair by the grave of her brother, one of the first victims of the protests, shot dead by the anti-riot police. And like all others taking part n Gisuboran—in the name of the movement—she too acted in d fiance against the oppressor who killed her brother and tried to silence her voice.