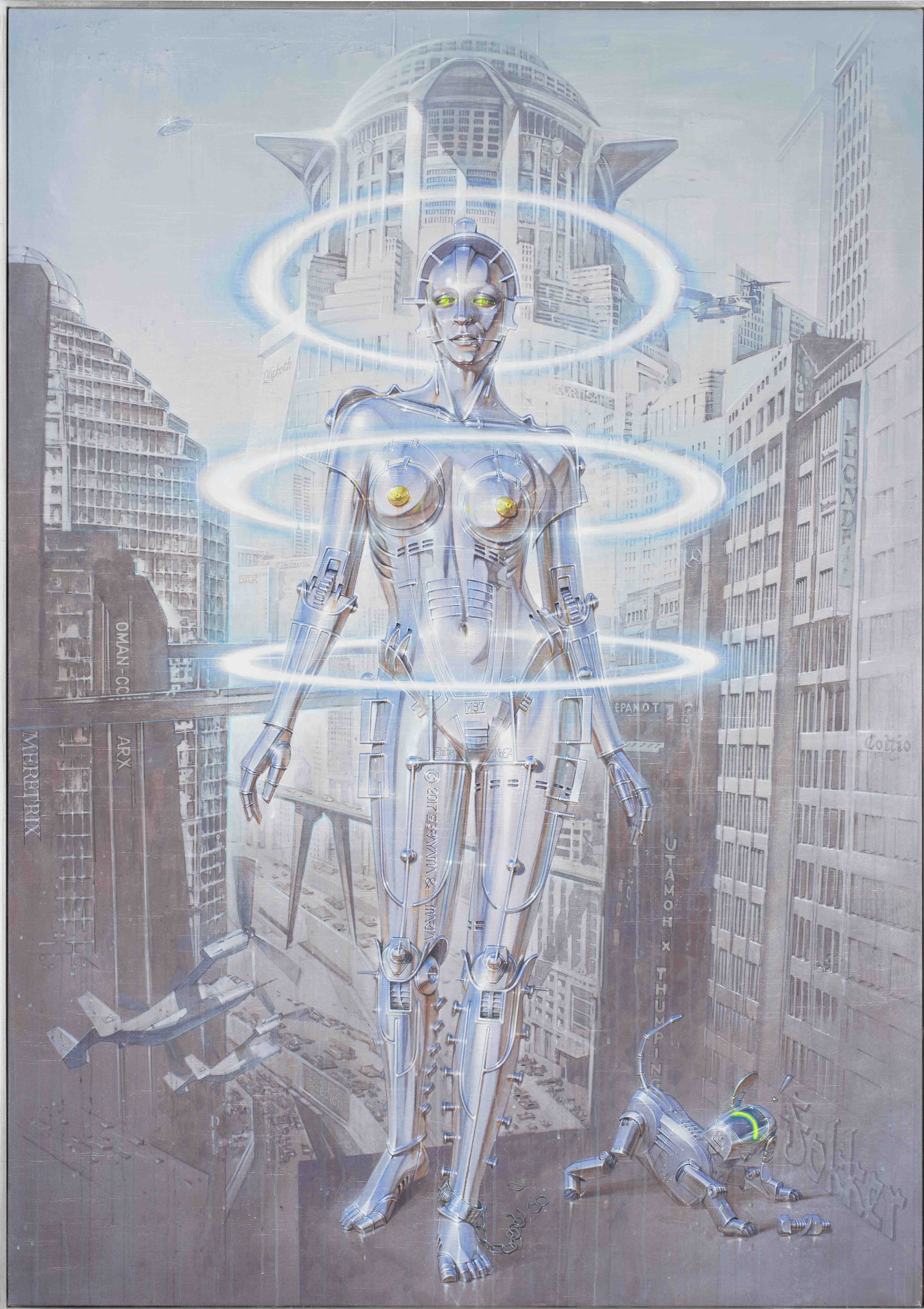

Impoverished by its dominant association with the sexual interest in an object or part of the body, the term ‘fetish’ can also be used to mean the interest in an object or activity that makes one spend an unreasonable amount of time doing or thinking about it or an object that is worshipped due to the belief it has spiritual powers. Asking “shiny metals…are sexy, right?”, Japanese illustrator Hajime Sorayama’s chrome fetish can also be understood through the lens of these broader definitions.

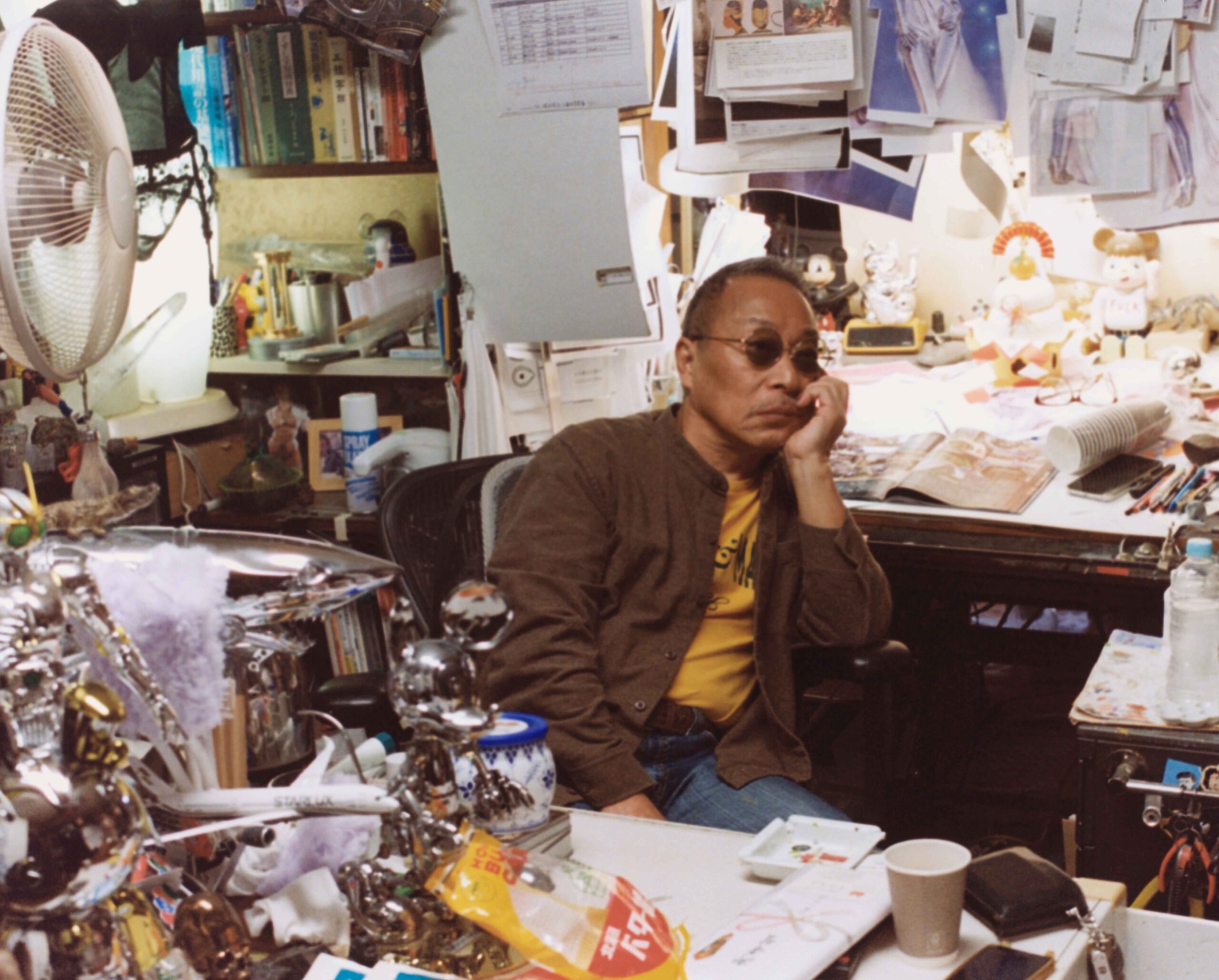

Born in Imabari, Ehime prefecture, Japan in 1947, Sorayama later moved to Tokyo to study Art at the Chuo Art School and work as a freelance illustrator, where he received a commercial commission that led him to paint his first ‘sexy robot’ in 1978. Producing hundreds of ‘sexy robots’ thereafter as part of his ongoing Sexy Robot and The Gynoids series, for almost half a century Sorayama has spent what, to some, could be considered ‘an unreasonable amount of time’ relentlessly pursuing the visual illusion of light, reflection and transparency through his mastery of the airbrush technique, which—he explains—was already being used by female Japanese artist Harumi Yamaguchi for her progressive Harumi Gals series in the late 1970s.

Despite its relatively conservative culture, the image of the beautiful woman has long been used for commercial advertising in Japan. Coinciding with the global woman’s liberation movement of the late twentieth century, Sorayama’s ‘sexy robots’ and Yamaguchi’s ‘Harumi gals’ represent the genesis of a new kind of woman that was being demanded in Japan to define the modern female consumer, and that continues to attract a cult-like following today. While they may, at first, appear irreverently superficial, Sorayama’s works reflect the independent woman who has attained freedom and empowerment. Referring to his creations as ‘she/her’ and imbuing them with distinct personalities that emanate agency, autonomy and unapologetic confidence, Sorayama—a self-professed “mama’s boy”—unequivocally supports a future in which women take the lead in society.

The subject of a major solo exhibition titled Light, Reflection, Transparency at Nanzuka Art Institute in Shanghai, China, from his first ‘sexy robot’ painting to the monumental 12 metre tall robot commissioned by Kim Jones for Dior Homme’s Pre-Fall 2019 menswear show, Sorayama’s most iconic works will be on display at The Summit between 28 February and 15 June 2025. When asked how it feels to have his extensive archive of works on display as well as in the permanent collections of prestigious institutions and museums, with his characteristically lighthearted, subversive and youthful sense of humour, Sorayama quips, “Please keep making them bigger and more extravagant!”

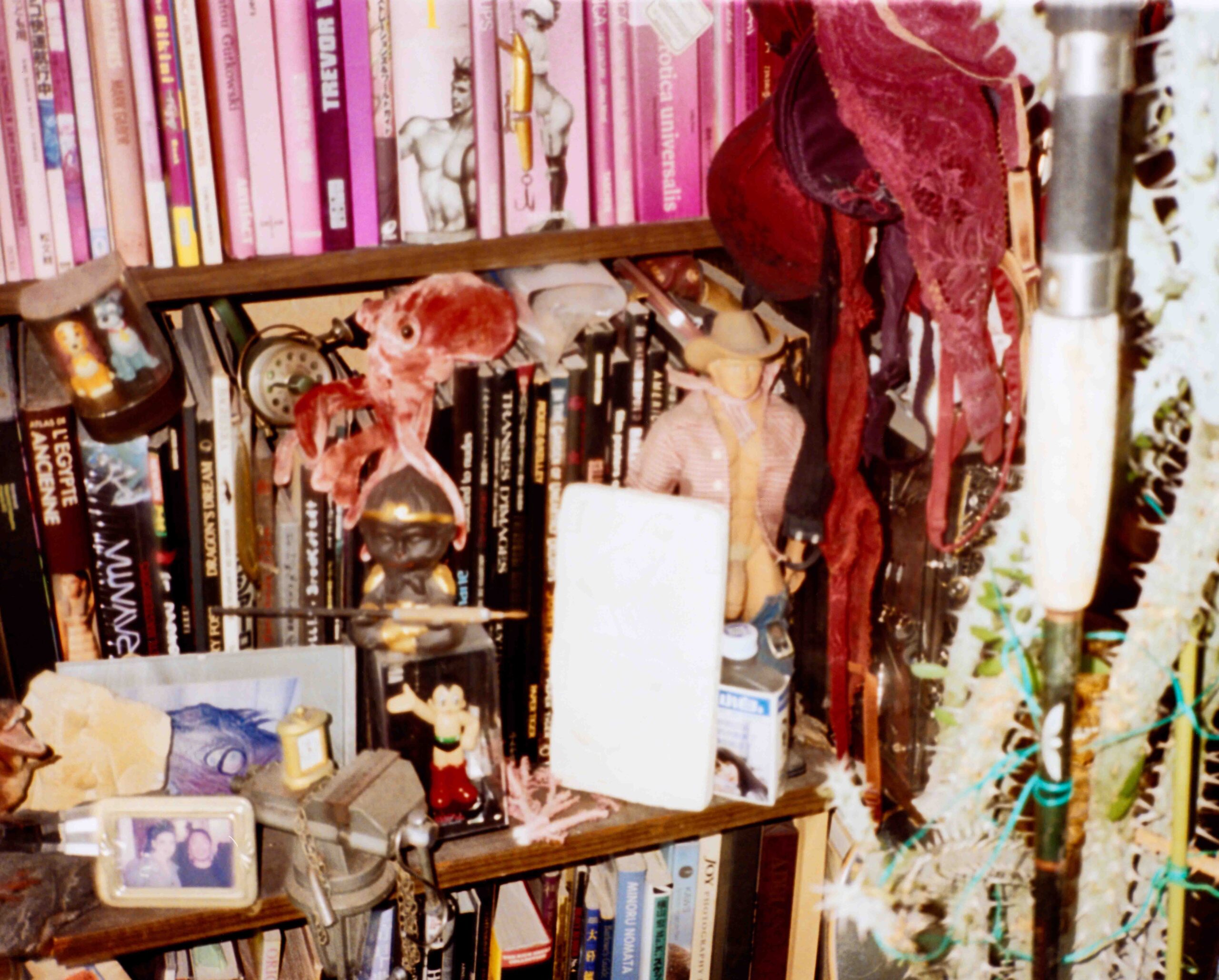

It was the fantasies and yearnings of my adolescence. As a child, I never imagined I would make a living from drawing… Whether it was pin-ups or dinosaurs, I was just playing around, continuing from the scribbles I made as a kid.

I just want to draw better than anyone else. I’m depicting what I believe to be the most beautiful women and the coolest things in the world, so I don’t care what others think and I don’t feel guilty about it. Above all, I am forever a mama’s boy.

NO! I am not telling you!

I think the passage of time played a role as well. Back then, I took on any commission work and was determined to draw better than anyone else, so I think I would have eventually drawn it anyway. I’ve had a fetish for metal ingrained in me since childhood, and I think it just came to the surface at that moment.

I always say this, but I want to surprise people with my paintings. Every artist knows that there are many things that can only be expressed through painting, and to achieve that, I want to use whatever tools are available. The airbrush technique was already being used by artists like Harumi Yamaguchi, so I started using it by watching and mimicking others.

It’s different for everyone. That’s what fetishes are all about. I’m not aiming for perfection; I’m pursuing my own eternal yearning. I’ve never thought about following anyone else’s way.

It’s a bit of a secret, but those are humans covered in metal skin. With metal, they aren’t confined by AI codes and they aren’t recognised as human. Pushing my own aesthetic in this way is one of my strengths. Japan, on the surface, seems free, but in reality, it’s quite conservative. There’s also an influence from Western ethics. I think China is different, though I don’t know much about it. What I do know is that I have many young female fans there. It’s an honour as a man, and I’m grateful. [Laughs].

Of course! Each one is unique, with her own personality—my daughters. As I mentioned earlier, they are humans covered in metal skin.

It might have worked [out] that way, but for me, both sex and metal are my motivation. Shiny metals and minerals are sexy, right?

Kim came to the opening of my solo exhibition at Nanzuka [in Tokyo], acting all important and taking photos as if it were his own exhibition. [Laughs]. So I asked, ‘Who are you?’ The next day, he came to my studio, and we started talking about the collaboration and creating that sculpture. Since we began discussing the collaboration in July, it was a huge challenge for me to finish it by the November show. Well, Nanzuka handled all the dirty work, so I was good. The day before the show, we were told to dust off the robot’s body. Nanzuka was tickling the robot with a dusting stick, which was hilarious. After the show, she’s been sleeping in the Nanzuka warehouse, and now, finally, she’s waking up for this exhibition. I think she’s very happy about it.

Please keep making them bigger and more extravagant! My goal is to reach the pinnacle 1000 years from now, so anything that helps me get there is more than welcome.

Even though technology has advanced, if humans haven’t progressed then, in the end, not much has really changed. So, I don’t think anything has truly changed. I don’t think that’s a bad thing, though. Life is about enjoying yourself—if you don’t, you’re missing out.

I plan to live to 300-years-old without relying on technology, so I’m not really expecting that. My friend, Keroppy, is a body modification researcher and is trying to use technology to extend life, but that’s not something I feel is necessary for me.

In this world there are men and women, and it’s simply a fact that we have sex and children are born. So, I don’t think it needs to be hidden. I’ve been saying this through my work for a long time, but society has many restrictions. I believe things will change if women take the lead in society, and I support that.