Following the publication of the photo book, De Cara Al Sol in late 2023, Diego Vourakis is reflecting on what it means to be a photographer with Present Space’s Juan Duque. The project, which centres on Cuba, helped refine Vourakis’ worldview and also allowed him to reconnect emotionally with Peru, the country in which he was born and lived as a child. Vourakis emigrated from Lima to the United States when he was 12 years old. As a teenager living in a new country, he experimented with fashion design as a form of self-expression and creativity, before later discovering a passion for photography. Since then, Vourakis has established a career as a fashion photographer, working for clients such as Dior and Nike.

Over the course of three visits to Cuba between 2020 and 2023, Vourakis travelled the length of the country, spending periods of time with different communities and immersing himself in their ways of life. De Cara Al Sol, focuses on five cities in Cuba that Vourakis felt most connected to, from Viñales in the west, through the La Habana province and Trinidad, to Santiago de Cuba and Baracoa in the east. The intention of the work for Vourakis was to capture a sense of Cuba that wasn’t obscured by romantic depictions of the country as an idea and a tourist destination. Reflecting on the project, Vourakis says “it’s awesome to see just how much this project has achieved and taken on a life of its own, when it just started out as a trip.”

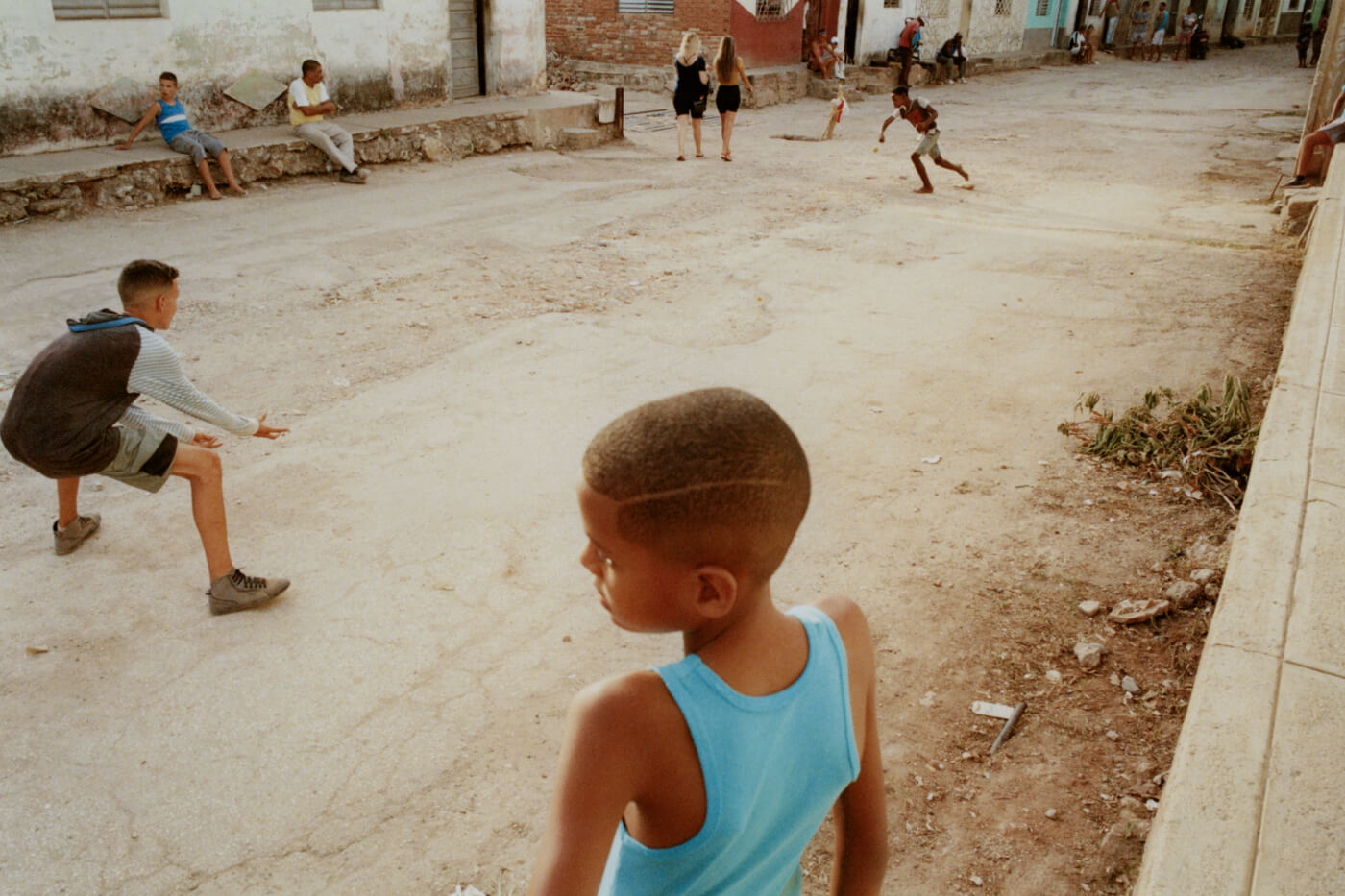

Throughout De Cara Al Sol, one of the recurring themes that runs through Vourakis’ images explore childhood and the memories that are forged during that age. This is something that deeply resonates with the photographer, as something that he uses his works to capture. Vourakis describes one image in particular, of a young girl hanging upside down from a climbing frame while other kids play in the background. “While I was taking this image,” he says, “I had this rush of a feeling that I experienced a lot in Cuba, which was this feeling that allowed me to unlock memories.”

Seeing the kids in the park as they ran around carefree, recalled afternoons in Lima when Vourakis was a child. After a post-lunch nap, the street he lived on would spring back to life at 4pm. “That’s the time that everyone in the street would come out, yell your name and knock on the door: ‘Let’s go out, it’s time!’” With his brother and friends that lived on his street, they would play games like hide and seek and football. Vourakis recalls the sense of freedom that came with being this age, “it’s one of the happiest memories I have of this age,” he says, “which was when I was probably around six or seven.” In that way, Vourakis uses photography as an ode to childhood, and a way to capture a sense of what “happiness used to feel and look like” as a child.

Community is something that Vourakis also reflects on, as something rooted in his memories of growing up. He describes the “different senses of community” that he has experienced between Peru and the United States, and in particular one of the starkest contrasts between living in the two countries. “I have this thought that sometimes comes to my mind about my life here in America, and what happiness meant and felt before I moved here. How did that feel? I remember that there wasn’t much, in terms of what my family had. But there was more community; it was more about your interactions with people [that you knew] rather than about status. I grew up in a very poor area,” Vourakis adds, “so that makes a difference too. When you’re living in similar circumstances [to the wider community] everyone’s there to help each other and to be there for each other.”

Vourakis describes the emphasis on community life that he remembers as being similar to that which he encountered in Cuba. “It’s very inclusive, I guess, in Cuba and Peru, in the way that almost everyone on your street—you’ve gone into their houses. That’s something I haven’t had so much [in the United States] because privacy is more enhanced here, certain things like that.” As such, something Vourakis was able to really reflect on during his visits to Cuba was this different emphasis on community: “It just reminded me of how things should be, at least for myself [in terms of] what the family means, what community means, what friendship means.”

“That essence of who people are, and what brought me happiness at that time, that makes me question the decisions I make. And so going to Cuba was a reminder that this core happiness exists—stripped back from [material excesses]. It doesn’t matter who you are or what you do. That really was a big change in my perspective for what community is, and it was a reminder, for myself and my friends, that you can get stuck in a cycle.”

On the experience of working on De Cara Al Sol, Vourakis says that, even though it has been a solo project, it has brought him closer to the friends and peers around him that have supported him along the way. “I’ve been lucky enough to have my closest friends work on this project. So that alone has taken our friendship, every single person that’s been involved in it, to different levels, not just personally, but also professionally, and in between. I feel like it’s just been making us closer, especially considering the nature of what this book is.”

It has also helped Vourakis clarify what it means to be a photographer and a person. “Before this project, I would question myself and think to myself, ‘Why am I doing this?’ I think this project has given so much meaning to what I do. Now, things are much clearer as far as where I want to go in the future. I think I’ve always navigated alone, especially with the type of work that I do. It always has a crew involved but I take care of my part. But with De Cara Al Sol, there were so many moving parts—it was much more of an expanded project—and that has definitely been one of the learnings/challenges of the project.”

Going forward, future photography projects will explore similar themes to the ones that De Cara Al Sol brought to light. “I hope to be able to keep doing this, and to figure out a way to make this sustainable and use the resources I have to get people involved in what we’re doing, to want to know more about [mine] and others’ cultures. I feel like, if I read about how a culture approaches something and I feel connected to it, perhaps it will serve as a reminder to myself to do it more. And that’s the goal, to be able to create those conversations, and be able to inspire people to think about their background and past—to see how they can do something with what they feel connected to as a project. To say, ‘This is what I felt connected to at this point in my life.’”

Vourakis hopes to achieve this under the umbrella of AMILE, the creative studio he co- founded with Duque and Present Space’s Nima Habibzadeh in 2023, which was also responsible for the publishing and creative direction of De Cara Al Sol. “The goal is to bring more projects to life, to work with other creatives and photographers to create their own photo books, and to see how we’re able to use the resources we have [at our disposal] to get more people on board and make the studio as impactful as it can be.”

Next, Vourakis plans to return to Peru. “Going back and doing a bigger project there, revising my roots and exploring myself more. I think that everything will stem from that as well. It just feels like the next right step to make. There’s so much beauty there that people are not [necessarily] aware of,” he says.

For someone like Vourakis, who came of age in the United States but is also eager to revisit Peru, the country from which his roots are based, what does home mean? What he describes is not concrete, but something more abstract. “Home,” Vourakis says, “means community. It’s leaving your door open so neighbours can pop by and have a conversation. It’s a sense of openness and love towards each other. It’s a feeling of comfort within your community that feels home to me.”