The Paris-based architect and digital designer, Nicholas Préaud, has had an appetite for 3D software since he graduated from studying architecture in 2013. Préaud started out working at studios as a junior architect designing, modelling and creating digital imagery for projects. “As the years went on,” he tells Present Space over Zoom, “I got better and better, and eventually just started doing it for myself.” 3D software has, Préaud says, “proven to be a very valuable asset.” And that’s not an overstatement. Even if the architect and designer fell into using 3D software, there’s now huge demand for the kind of design he has come to specialise in. These days, splits his time between real-life architectural practice, digital design and R&D (research and development). Dreamy, cool and airy environments are characteristic of the designer’s digital – imagined – spaces. In the lounge space of Villa del Soffio, for example, golden sunshine softly illuminates the serene interiors. Seen from outside, meanwhile, we see how the villa protrudes from a cliff face, hovering above the glistening beachfront. If you look closely, a sun umbrella and two deck chairs are one of only a few signs of life. Of course that’s kind of the point; the villa is a digital render, made with Préaud’s regular collaborator, the digital interior designer Charlotte Taylor. That’s not to say that the digital and the physical cannot overlap – as Préaud discusses below, Casa Atibaia (another digital collaboration with Taylor from 2020) has attracted interest from clients who want to see the project built in real life. When I speak to Préaud over Zoom, he has just unveiled Timeless Ruin, a project with Manuel Cervantes, in which an imagined wooden structure takes the form of an inverted pyramid. Again, the two collaborators hope Timeless Ruin can be conceived in real life. The “whole point” for Préaud is that the digital might inspire the physical: “I see it as research,” the designer notes. “When my calendar opens up and I get a bit more free time, I’ll say, ‘I saw this item which made me want to explore this idea.’ And then I’ll [work on that] as personal research, but that absolutely [also] nourishes my portfolio.”

We usually have a starting point which would be either an architect or artist that we would want to be inspired by. That was the case for Casa Atibaia (with Charlotte Taylor), which was inspired by Lina Bo Bardi, a Brazilian architect, and it was inspired by Casa de Vidro, the home that she built for herself. The point is to pay homage to past architects in our work and add that extra layer of what we can bring to it. To me, that’s fine as long as that’s openly expressed, rather than trying to copy something and make it your own reference. And in terms of constraints, my background is architectural; I’m an architect in France. I also have real-life projects that are being built. So both practices nourish each other. I also see R&D as important. These are [the] very down-to-earth, real-life problems where you have to connect the architectural elements together. But the more artistic projects are the most fun, where there aren’t really any constraints. It all depends on where you want the project to go. There are many 3D artists who don’t necessarily have an architectural education or background, and they create dreamier [spaces] that are not bound by gravity or physics. I try to keep it real in a way; when I’m designing, I always ask myself if this could actually exist, and then push it to the very limit of what would actually be possible in real life. But we’re still in that realm where, if we had to actually build it in real life, it wouldn’t be so different from what’s being designed.

There are no constraints apart from the ones you [create] yourself. But absolutely, that’s the whole point. It creates this illusion, where people might actually think it’s a space that exists, or they might think it’s a picture. That’s the thread I’m trying to walk on, where you’re looking at it and you think it could be a space that exists. You can push that sense of reality one step further, and try to also keep a sense that you could feel as if you could be walking through it. It extends the artistic possibilities with projects that aren’t necessarily commissioned or paid for by a client. It’s a way to do research, which is extremely satisfying because, if you’re only doing client-based work, then you’re only working in the realm of what you’re commissioned to do. But the blank canvas of research is quite fun.

I don’t know if my answer would be valid for anybody else, but it works exactly the same. I have also worked on real life projects with Charlotte, and we work in the same way. In that instance, we have very specific skills, very complementary skills that work well together. She works with interior design and furnishing; small intricate details that make the design interesting. I have a more architectural approach, so on a bigger scale. And the mix of both visions works really well for us on the different projects we’ve done. It’s layers of information that we contribute that aren’t on the same level, but that need each other to coexist. But to answer your question – I like to stay down to Earth even on a digital project. In my case, the work is very similar to the real-life projects. And the approach is the same, it’s just not being built at the end. It’s missing that construction phase.

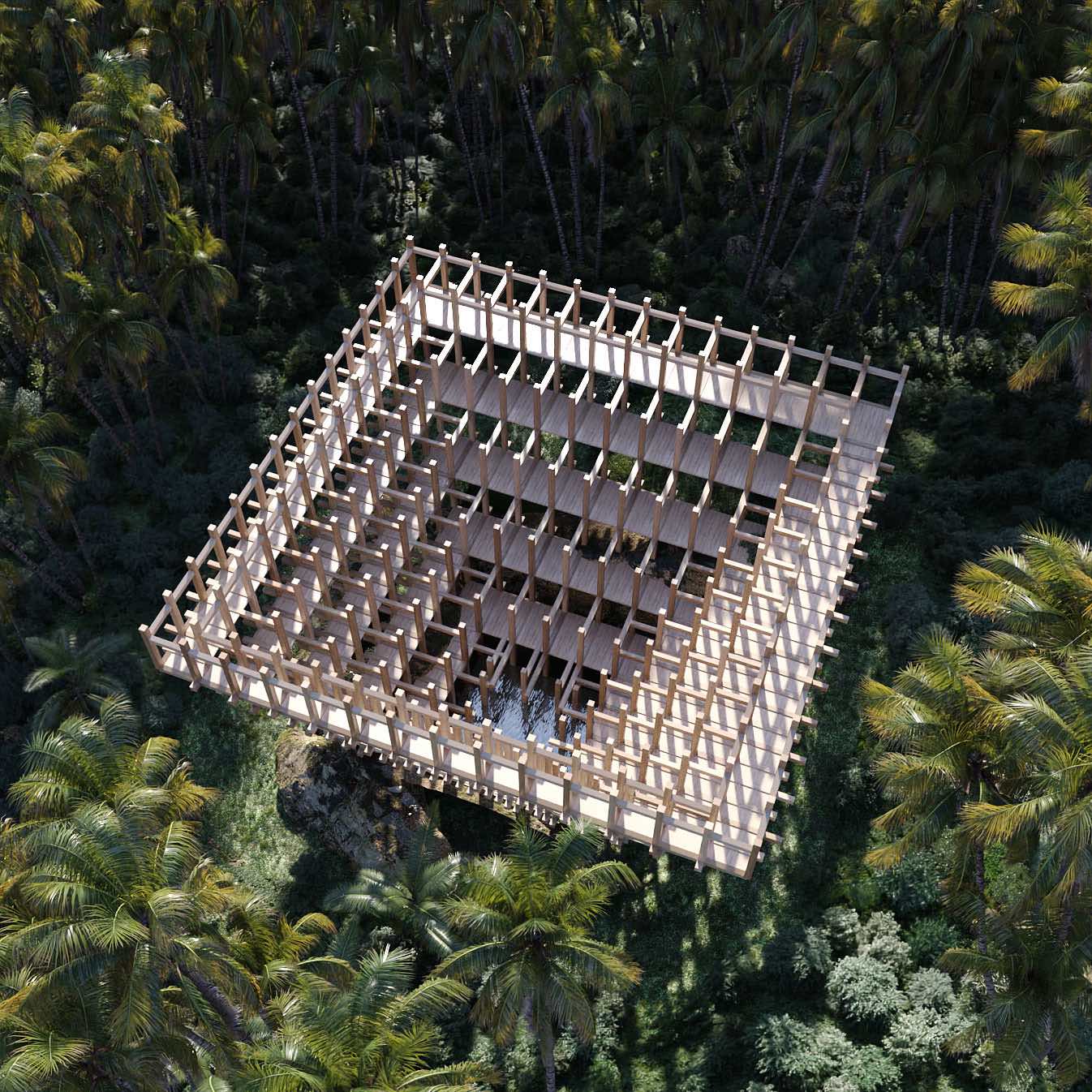

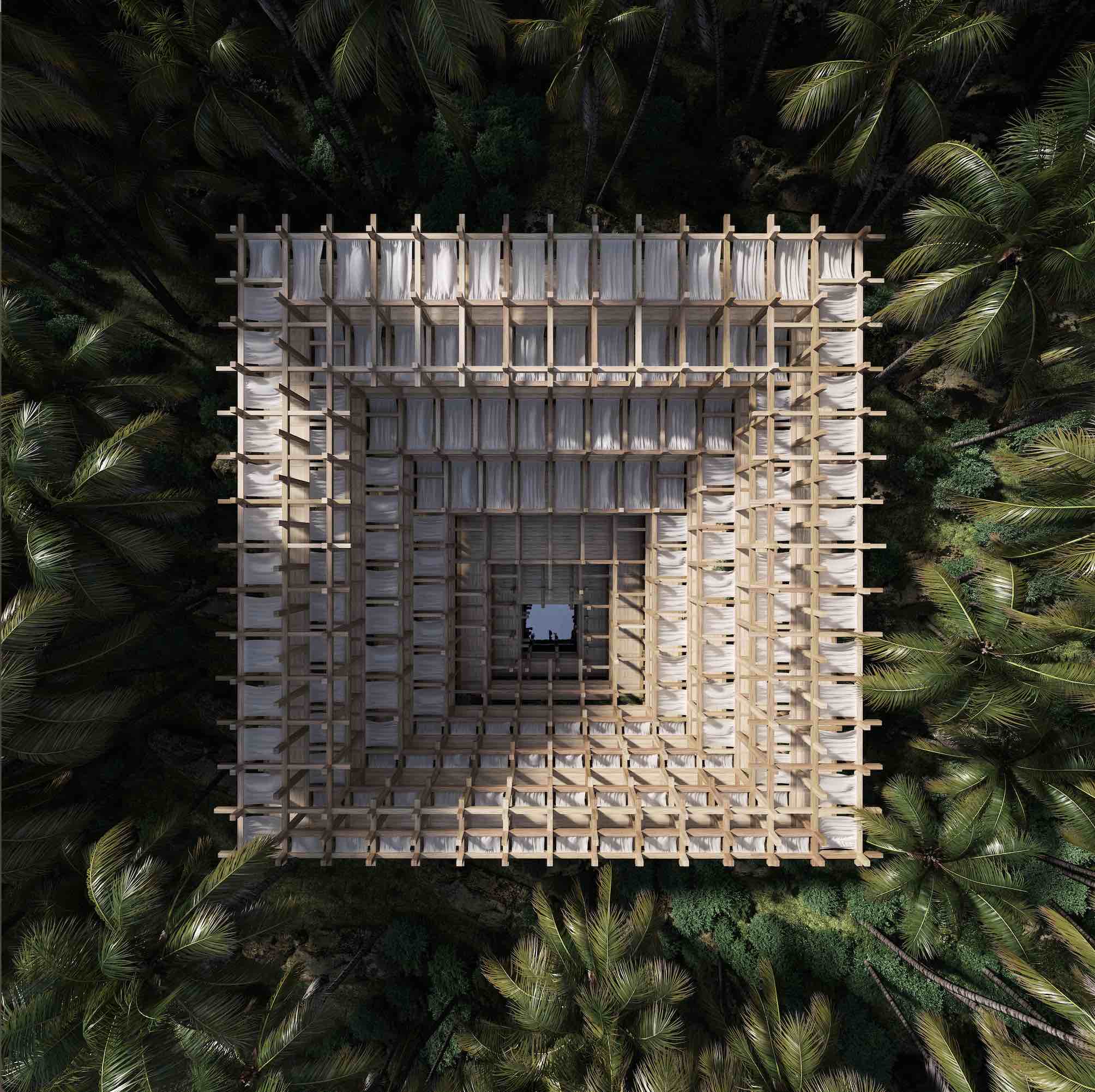

The approach we had with Casa Atibaia was to start digital. But now, we’re doing the absolute reverse of a traditional architecture real-life project; we designed Casa Atibaia, and we’re now trying to find someone who will be interested in building it. We’ve been in discussions with a client who wants to build it in the Dominican Republic. And this is way down the line – we’re not at all going to do this year or next year. I think that’s fun because now, all the projects that are realistic enough to be built in real life could absolutely be built. And that’s the case for Timeless Ruin, which I released this weekend [September 2022] with Mexican architect, Manuel Cervantes. It’s a wooden structure, and it is digital right now, but I’m dying for somebody to build it if we are able to. I think that what has also changed now is that there are [a number] of digital artists who emerged over the past two, three years, through COVID. They weren’t taken seriously, but now you’re seeing more and more interest and demand for converting these projects into real-life projects, whether it be furniture or interior design. Take Six N. Five, Argentinian designer Ezequiel Pini’s studio in Barcelona; they’re not architects, they work with video and graphic design. They’ve slowly transitioned over the past couple of years and are now building spaces and furniture you can actually handle. It remains art, but it’s slowly being converted by collectors, buyers or clients that are willing to take that risk of bringing it to the real world.

Exactly, and pushing the boundaries because whatever weird design you put out, it’ll get people asking questions. about how you could build this, or how you could make this. It’s a truly artistic approach that makes even the engineering and building process question itself.

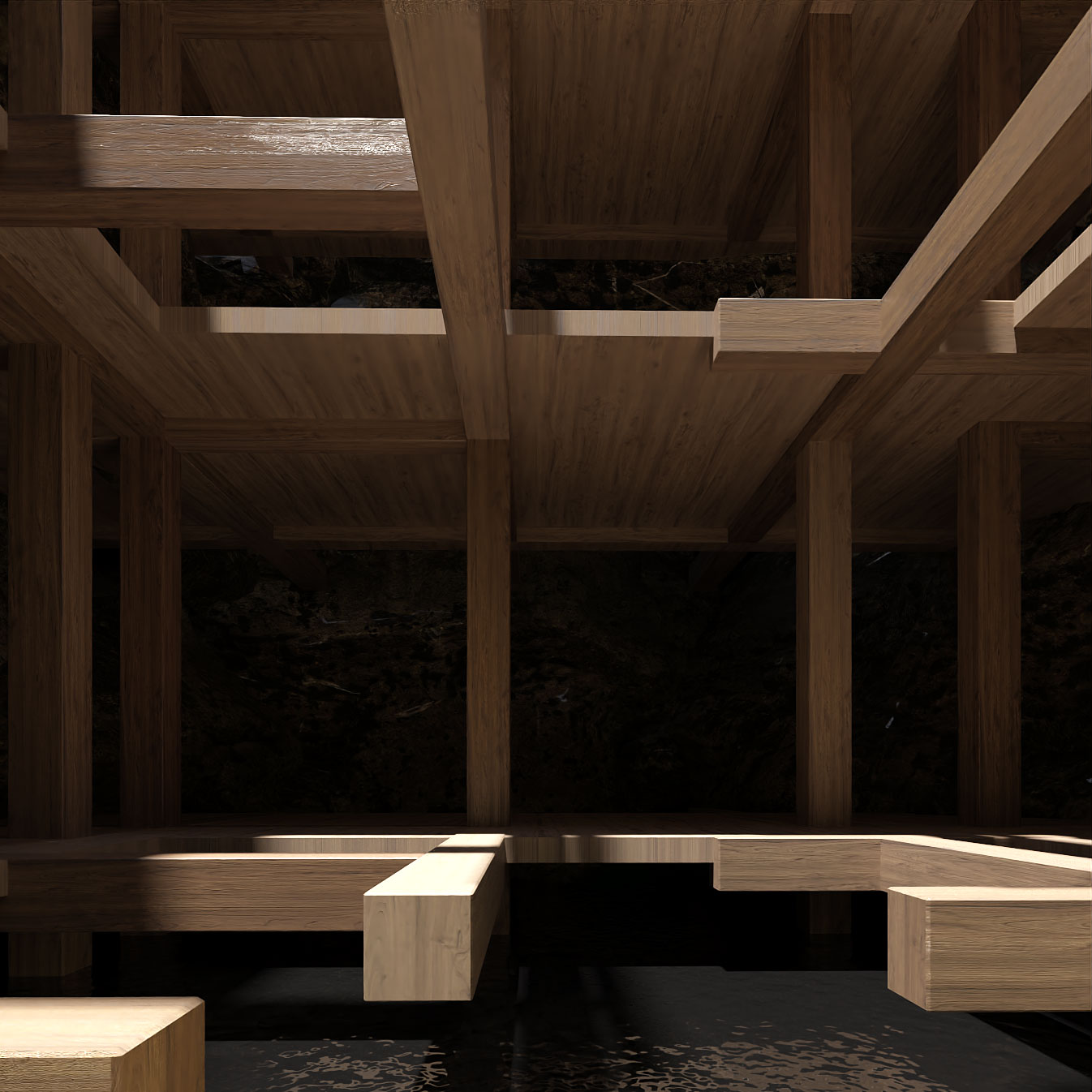

Timeless Ruin is an essay on the absence of human presence and activity – an homage to the beauty and invisibility of moving air. It cannot be seen or analysed through the prism of a purely functional, architectural building. It is a moving sculpture, a living structure – not through human presence but through life and movement of its own. This project was inspired by Dutch artist Theo Jansen’s wind-powered sculptures, Indian stepwells (historically used to collect water), and Mayan pyramids. The layout was also inspired by the colour square paintings of Josef Albers.

I see this structure almost as a temple; a structure sheltering the most valuable resource we have which is water. Elevating and opening itself into the sky like a wooden flower. Timeless Ruin is meant to exist independently from any specific human life, it coexists with all forms of life in the environment which hosts it.

So, as we discussed earlier, although this project exists, as of now, only in a purely digital form, it is meant to spark curiosity and was studied to be able to be built. As with Casa Atibaia and other projects, my hope is to one day be able to bring it to life.

These items and elements of the design process exist to highlight the architectural approach of this piece. It is indeed unbuilt architecture and comes with all usual media. They also contribute to make this project a more down to earth that exists digitally, but that could easily exist in real life too.