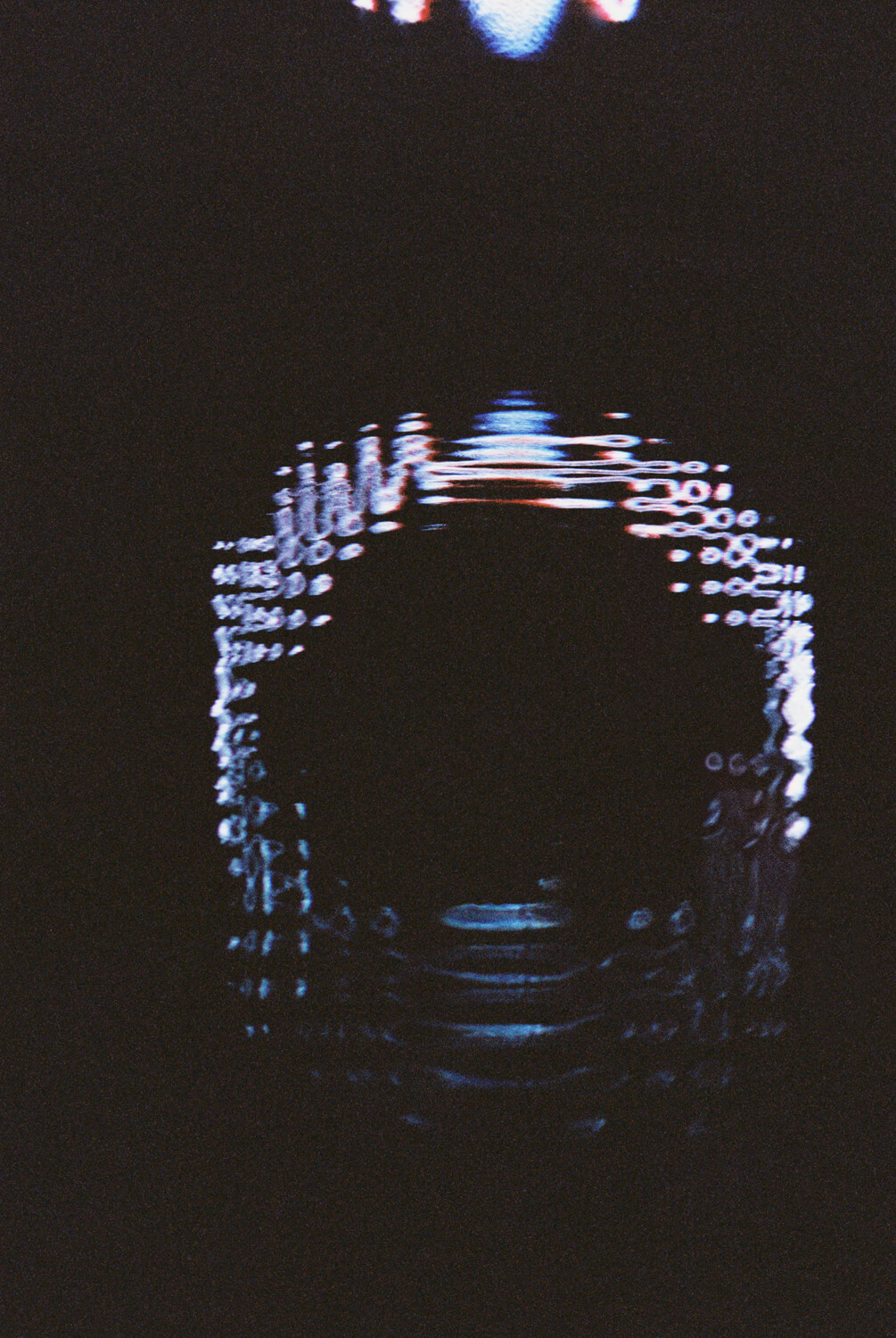

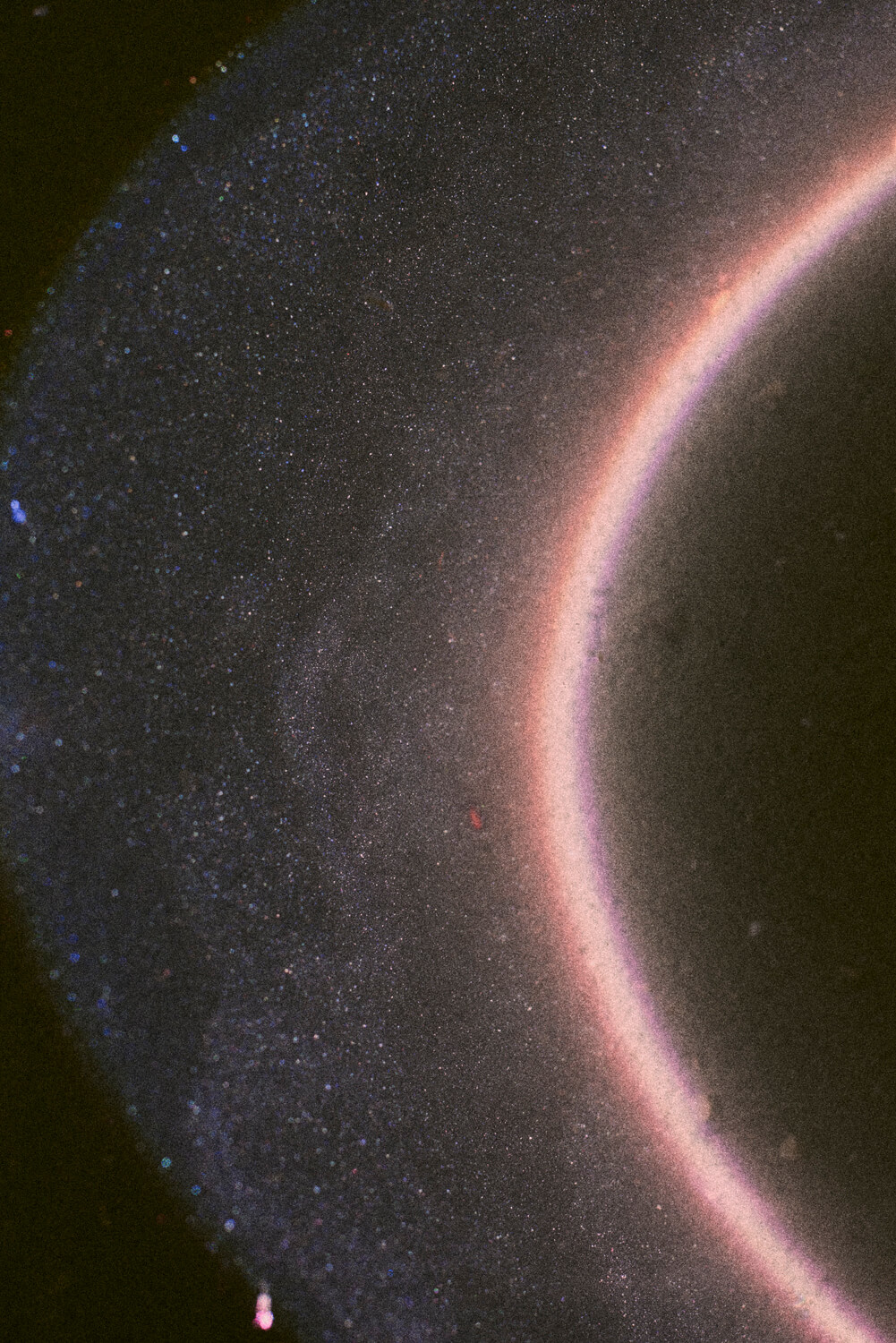

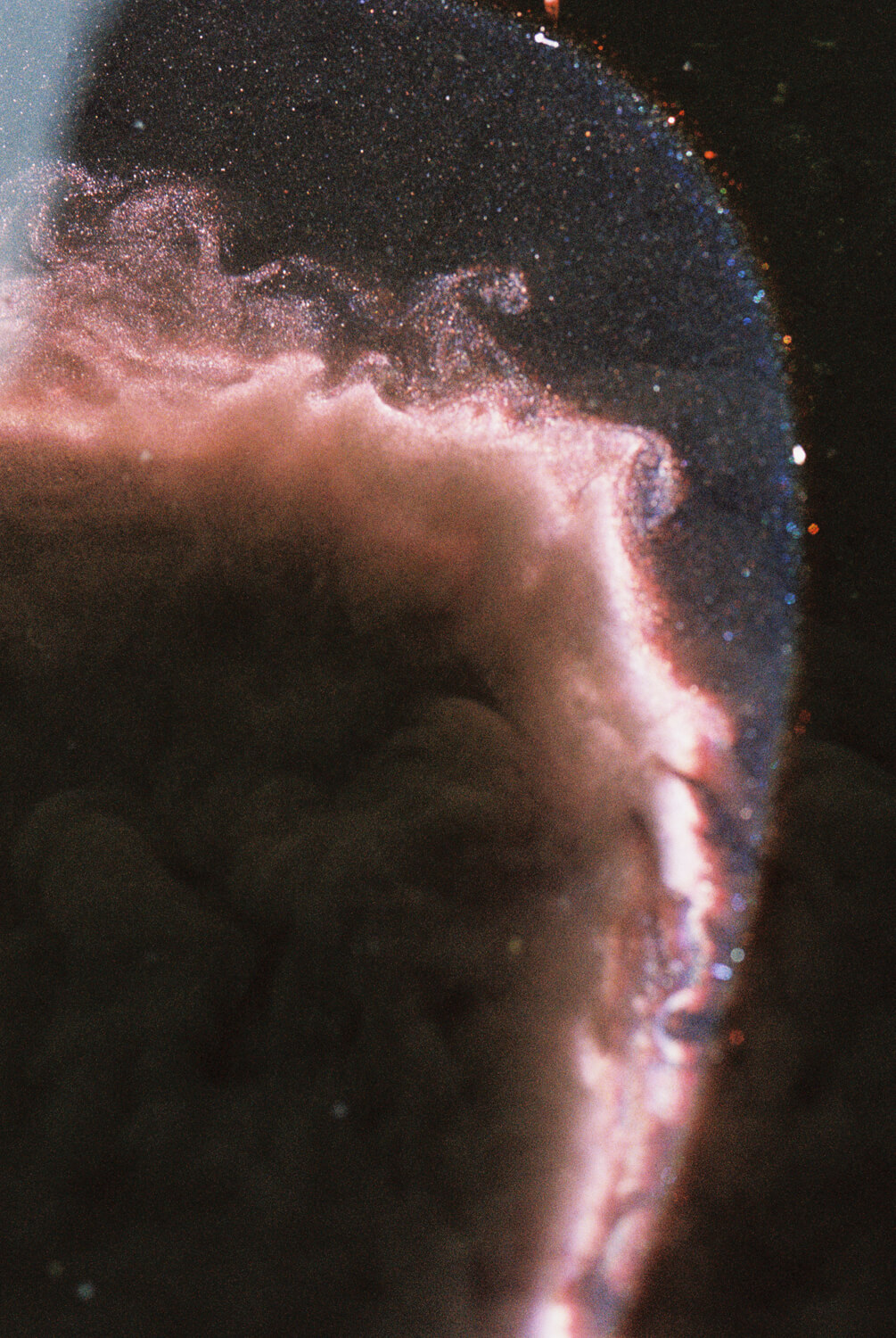

Lachlan Turczan creates expansive, emotional works. His materials are elemental. Many of his installations feature an interplay between sound, light and water, in which surprising properties of each emerge. By shining a coloured light through steam, this almost invisible substance is revealed in its full form. Bowls of water become a vessel through which sound waves are visualised. While he has created evocative works within cultural contexts such as Milan Design Week and at Kodo restaurant in LA, his pieces can often be found unfolding within nature.

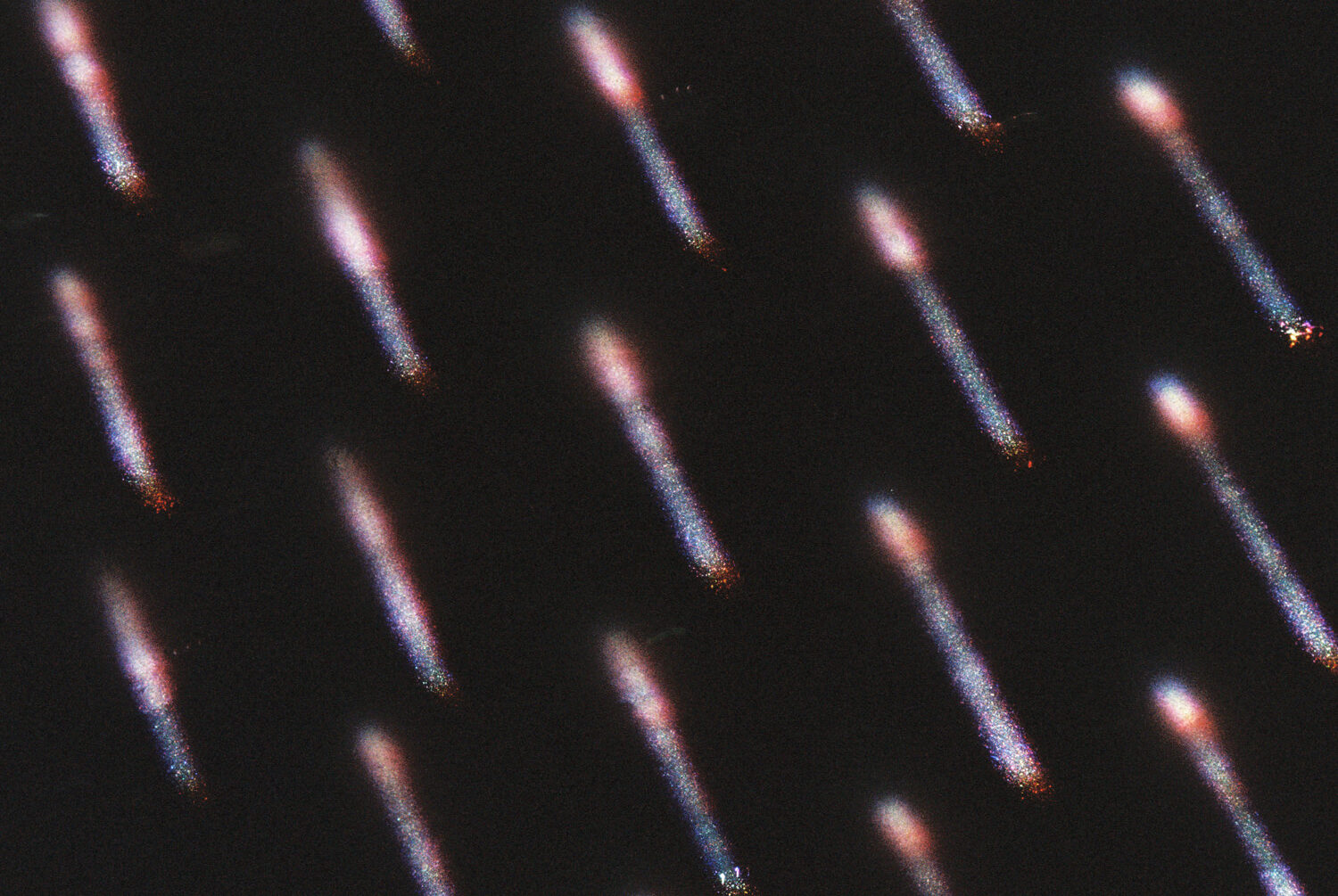

In recent years, he has installed ghostly veils of light in a flooded park along the Rhine; placed a sound sculpture within Death Valley’s Lake Manly; and illuminated a steamy creek in California’s Sea Ranch mountains. These interventions require meticulous planning and technological equipment, yet they capture something far beyond the rational. Many of his pieces both enhance and alter the world they find themselves in, reclaiming a sense of wonder in the substances we are surrounded by every day, and celebrating their natural settings. For Present Space, Turczan brought his volumetric light sculptures to the human-made Los Angeles River.

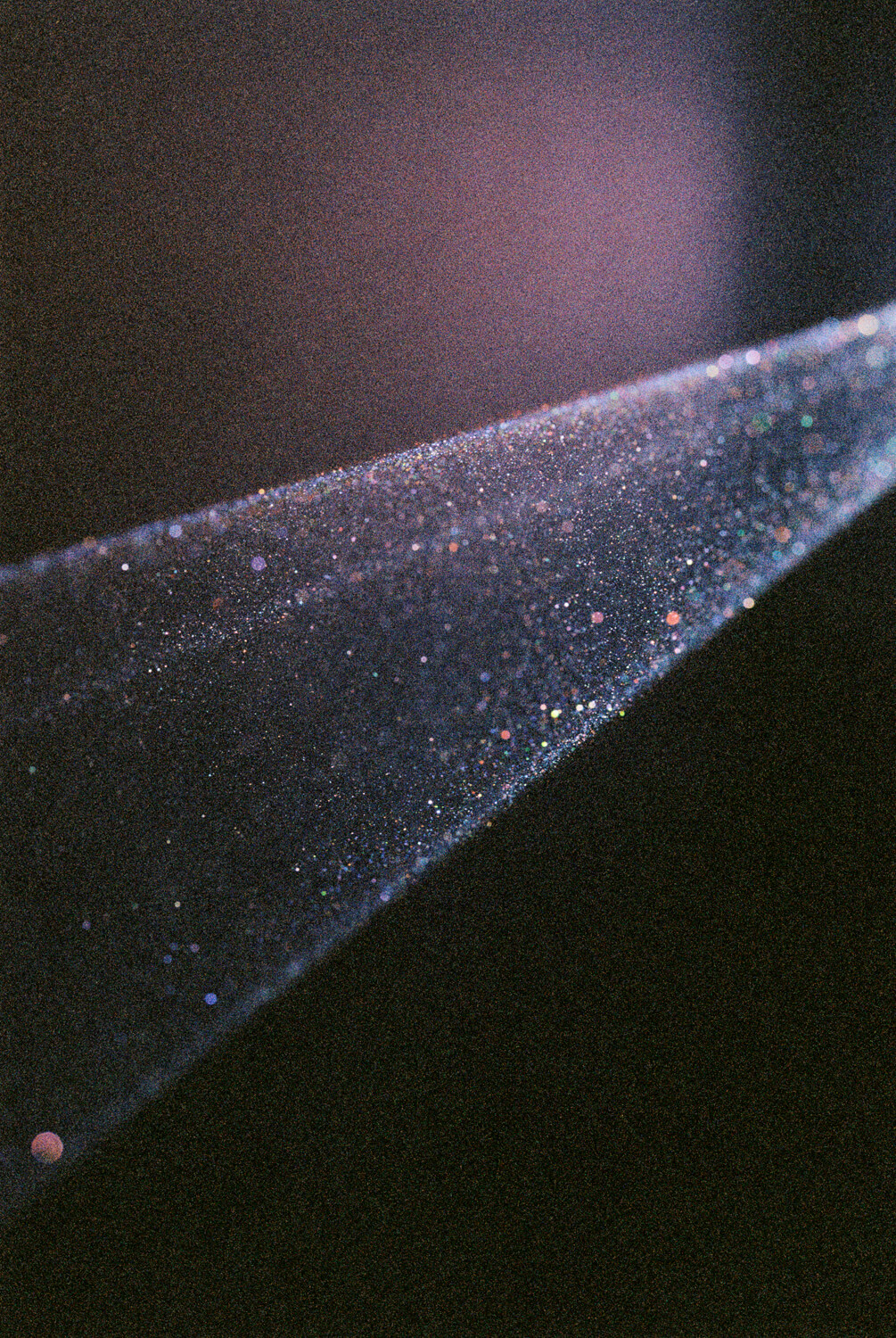

Growing up in LA and living here with this incredible landscape all around, it really does bring the studio outdoors. It’s like a Monet moment, taking things outside, because there is so much available. Then it’s an act of discovery. It’s a form of exploration, literally shining a light on the world and seeing what the world has to reveal. It’s a practice of thinking of light not just as something that reveals, but also an object in itself.

A lot of my work is so remote, it’s so difficult to get to. Oftentimes it’s just me and maybe my partner. So it’s for an audience of a few people. There was an instance [where] we did it on the side of the road in Death Valley, and all these people came by and they were like, “What’s going on man!?” It was really incredible. It’s really fun to share it.

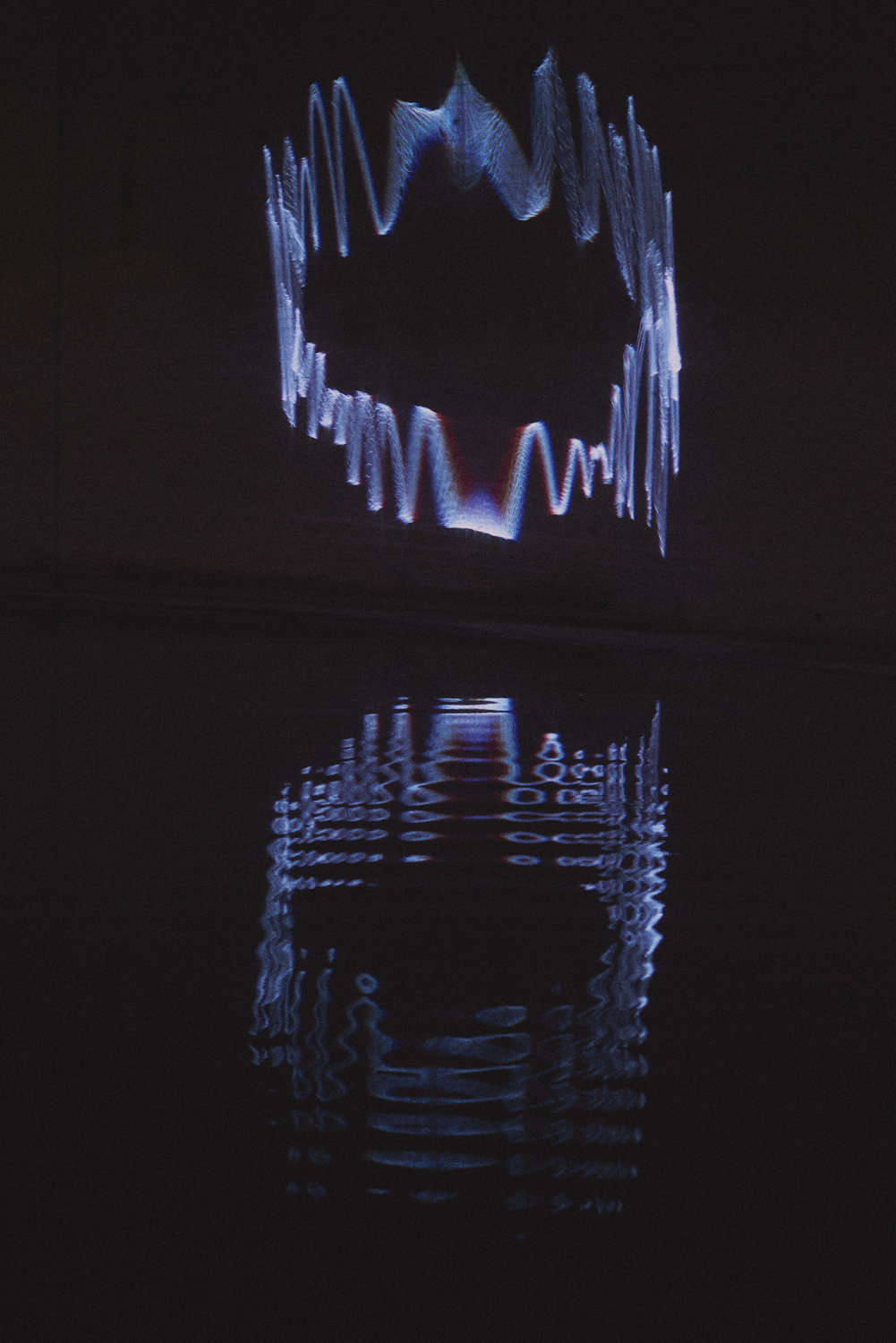

With a lot of my work, I try not to project too much. This is a philosophical approach I started applying when I was working with water vibrations. I was playing music through it, and if I played piano, all this emotional history came with it. If I play pure tone, pure sinewave, that also has associations and an alien feel, but it has as little of myself imposing on the viewer as possible. The thing I like the most about what art can do is that it can be a stimulus for someone to discover something in themselves rather than me providing a narrative.

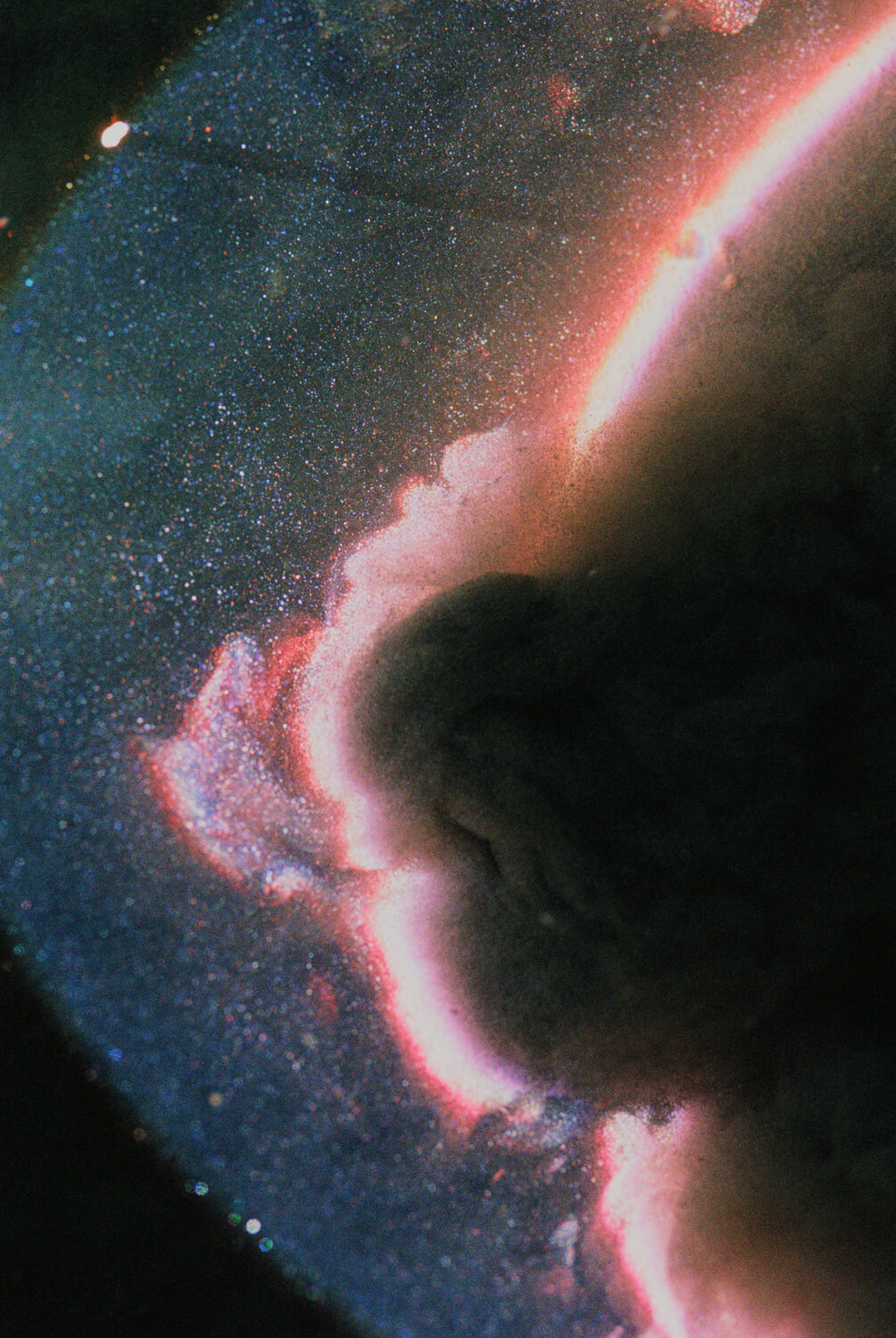

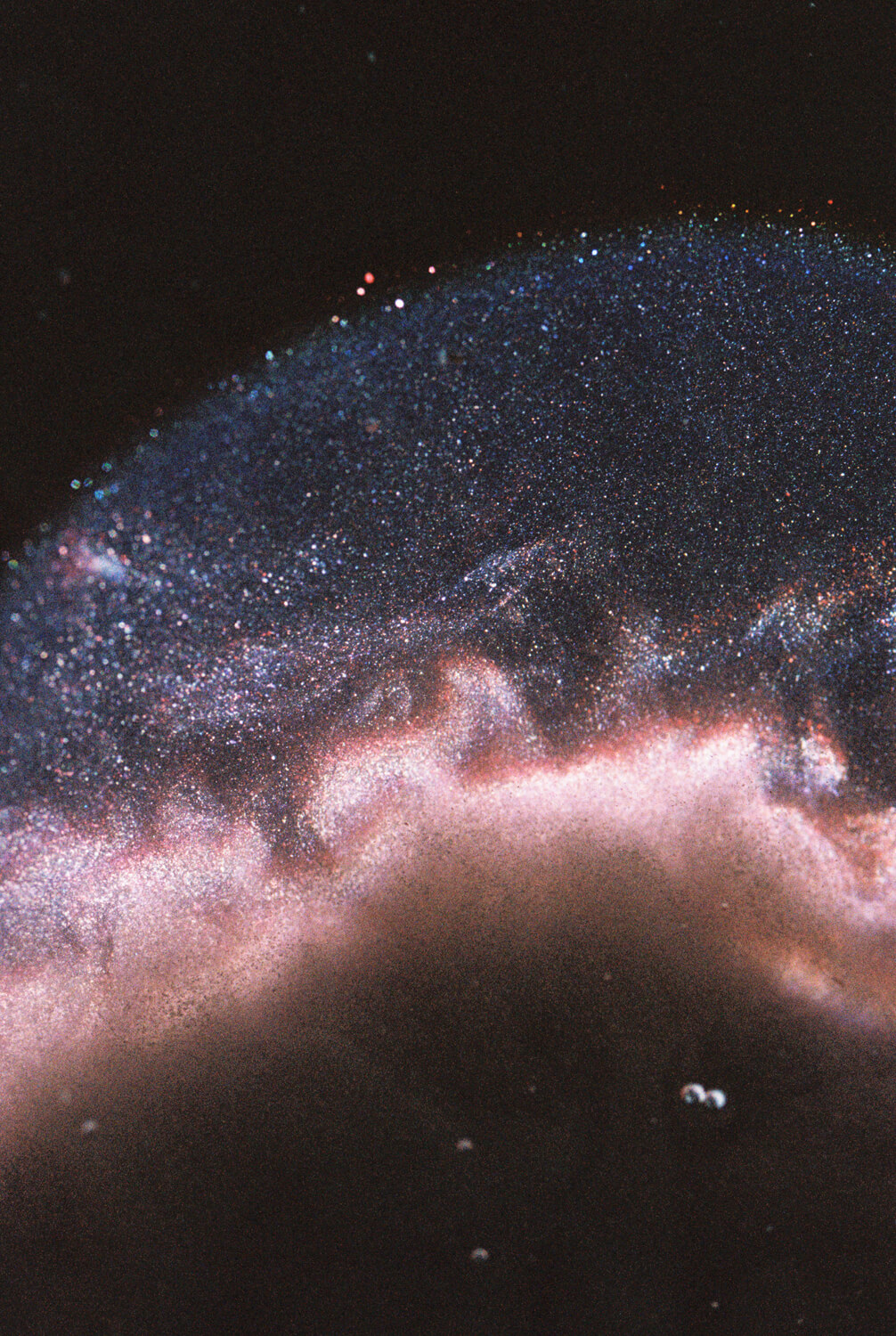

A lot of it is about giving this visual stimulus for you to co-imagine with. I have had people be like, “I have been thinking about this thing, and I’m seeing it in your work”. A lot of the water vibrations are these frenetic natural patterns. It’s like gazing into a fire or looking up at the clouds. You’re the one telling the cloud what the shape is; you can make it be a dog, a log, a horse, a tree. That’s what I want to carry in my work, the ability for anyone to see anything they would like in a given moment. Time and again, it’s these natural patterns I’m coming back to, but they’re already happening in the world. I don’t want to speak too directly to the problem of climate change, but it does make me think maybe the problem with climate change is that we can’t see what we’re doing. We’re spewing chemicals into the air; I think actually being able to see the air is a really important thing.

It’s something I can’t not engage with—I’m a water artist. I often pour small pools of water into these vessels; it’s like an uplifting and elevating of this ubiquitous material and it’s presented with such reverence that it becomes like a precious metal. Water is a life-giving substance. A lot of work I’ve been doing recently has been to instil a reverence for this material. People engage with water on a daily basis; they drink it, shower in it, water their garden with it. Maybe in my work they can have a completely new experience with it because it is this miraculous thing.

The water is a medium. Sound moves ten times faster through water than air. Dolphins’ and whales’ songs spread for miles through the sea. So water is an amazing sonic and optical substance. I was originally seeing the water as a way of making the sound visible, but it is literally holding the sound.

For me, it’s very exciting. I started looking at bodies of water within a city context, in and around LA. To begin with, I was looking for this perfect, pristine body of water that doesn’t necessarily embody the city. But I live across from the LA River, this giant concrete slipway taking all the runoff from the mountains into the ocean. So we decided to explore how nature and this polluted detritus full of moss and concrete can interplay. It’s this new foray into these really human-altered landscapes with laser work. When you shine light into the LA River water it takes on a whole new colour. There is life, pollutants. It shines a light back on us, it’s very revealing of what we’re doing.