Artist Carlota Guerrero uses a range of mediums, from photography and installation, to performance, to critique and explore notions of the feminine and what the female body means – historically and in contemporary society. In doing so, the artist sets out to challenge, celebrate and redefine the ways in which we think about the female body. Here, the artist’s collaborator, Mariona Valdés Torrella, discusses these themes within Guerrero’s work. Exhibited as part of WHO AM? / I AM exhibition at the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart last year, the sculpture Sofia Willendorf (2022) encapsulates the artist’s exploration of how the body is viewed, and by whom. Performance also plays an important role in Guerrero’s, such as Registro 8: Venus, Dolce, Paula (2023) and Registro 5: Ami Diao, Susana Balde, Chelsea, Ring Akual, Maria Sacko, Oumou Sabaly (2020). Both works, staged in museum settings, provoke viewers to consider their role in shaping, or affirming, certain perspectives when it comes to viewing the female body.

Scrolling through Instagram provides occasional moments of light relief, like coming across a meme that reads “when i catch myself trying to look sexy at home and remember “You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman.”” The second part of the meme comes from a Margaret Atwood novel, The Robber Bride (1993), which is followed by another sentence: “You are your own voyeur.” But are we really?

Multiple gazes coexist within one’s body. Trying to dismantle all of them would be exhausting and, perhaps, impossible. If one pays attention to the effects of gender on the matter, essential questions confront us: have we internalised a gaze and a voice that is not ours? How to recognise and recover our own? Are we capable of representing our own bodies?

To start, let’s look at Carlota Guerrero’s exploration of prehistoric Venus figurines. These are one of, if not the first, figurative representations of the female body in history. One of the most iconic of these, the Venus of Willendorf [from 30,000 BP], features in one of Guerrero’s sculptures. Titled Sofia Willendorf, it is a hyperrealistic sculpture that depicts a modern-day woman gazing down at the Venus of Willendorf figurine, held in her hand.

Sofia Willendorf was inspired by the historian LeRoy McDermott and anthropologist Catherine Hodge’s thesis developed in their article “Decolonizing Gender: Female Vision in the Upper Paleolithic” (1996). The authors challenge the interpretation of Venus “as [a sex object] made from a male point of view”. Instead, they argue, Venus was made by women, and for women, as a form of self-representation.

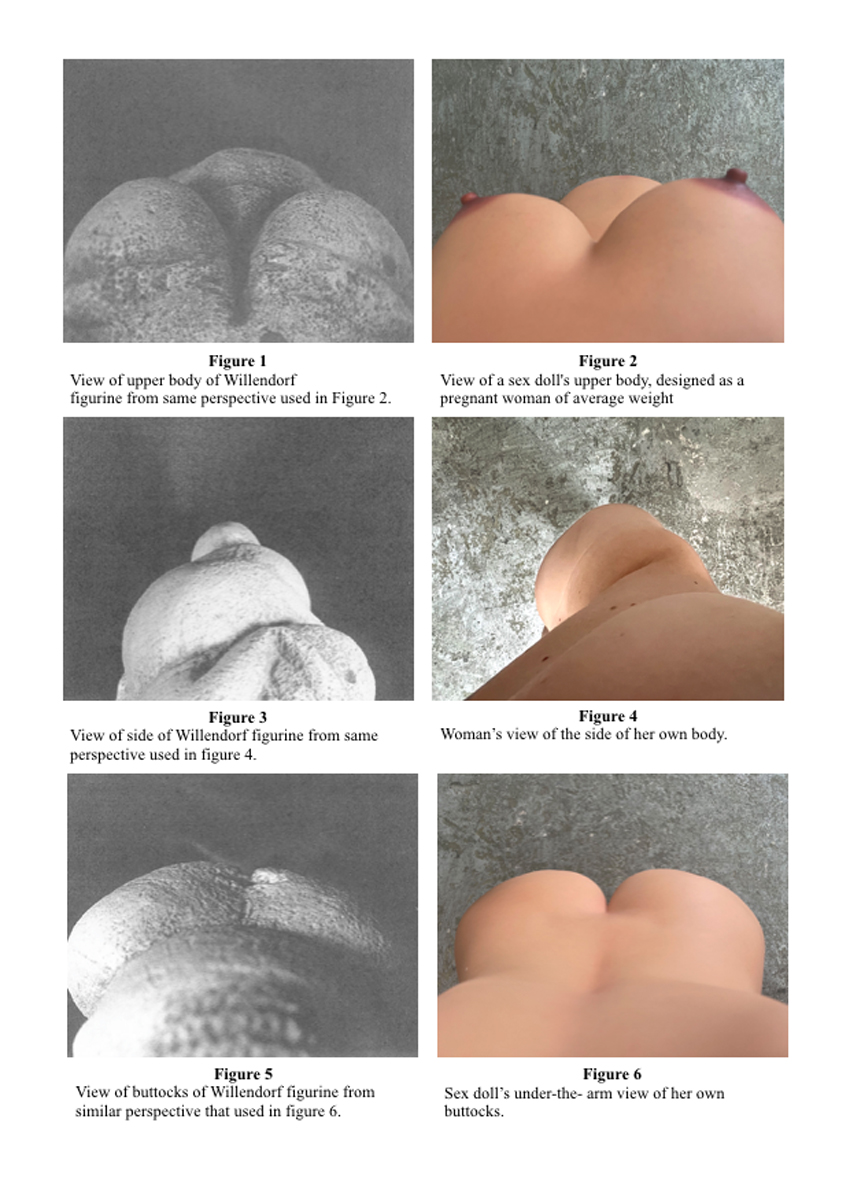

In their writing, McDermott and Hodge describe the features common to these Venus figurines: “a faceless, usually downturned head; thin arms that either disappear under the breasts or cross over them; an abnormally thin upper torso; voluminous, pendulous breasts; large fatty buttocks and/or thighs; a prominent presumably pregnant abdomen, sometimes with a large elliptical navel coinciding with the greatest physical width of the figure; and often oddly bent, unnaturally short legs that taper to a rounded point of disproportionately small feet.”

Just as Guererro does with Sofia Willendorf, McDermott and Hodge compare these Paleolithic statuettes to modern pregnancy, relating the distorted anatomies of the Venus figures to the perspective of their original creators. In other words, the researchers argue that these sculptures are accurate depictions of the female body – seen from the perspective of a woman, presumably pregnant, looking down on herself.

Though this theory has been criticised by some archaeologists (for only using figurines that fit the researchers’ argument), it does merit serious consideration. In fact, regardless of the thesis’s veracity, the essential question remains: why did it take so long to consider the logical possibility that a female point of view was involved? This is a rhetorical question with a clear answer: that is, thousands of years of patriarchy.

Sofia Willendorf gives voice to that pregnant woman in the contemporary context, where past and present archetypes are confronted under the veil of an imposed male gaze that Guerrero works to subvert. A certain discomfort emerges while staring at both Willendorfs – Sofia and Venus – separated by a 30,000 year gap. Originally purchased as a sex doll manufactured in China, Sofia cheerlessly exemplifies both the prevalence and the profound influence of the patriarchy.

Guerrero’s most recent performance, Registro 8: Venus, Dolce, Paula, represents another exercise in transcending historical bounds. Staged at the Louvre Museum in Paris, two performers are clad in white, draped garments posed in front of the Venus De Milo (150-125 BC). The expressionless look of the performers, absorbed in thought, is reminiscent of Venus herself. The triangle between performers, Venus and tourists also implies a direct questioning of the female gaze: how, and especially where, do we look from?

One of Guerrero’s previous performances, Registro 5: Ami Diao, Susana Balde, Chelsea, Ring Akual, Maria Sacko, Oumou Sabaly at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, works along similar lines. The performance examines the systemic lack of representation of racialised communities in the art world, for which the artist worked with six women who perform as “statues” in the museum setting. While the image of the performance speaks for itself, from an intersectional feminist perspective, it demonstrates that representation and the symbolic do matter.

Through her work, Guerrero questions the impact of the omnipresent male gaze, by focusing on the female perspective. In this vein, her work might be understood as an ongoing series of self-portraits because, as the artist herself states, she portrays women in order to understand her own condition. Indeed, one can observe certain similarities between the artist’s process and the Upper Paleolithic women who, in the absence of mirrors, supposedly sculpted their bodies in stone to bolster their own self-representation.

Because femininity is a plural and diverse concept that draws upon multiple sources, its social construction deserves our attention too. In this context, the French philosopher Luce Irigaray reminds us that, within a patriarchal society, the concept of the feminine is configured neither by what women are nor what they have been, but rather by how this has been historically constructed by men. In this sense, symbolic representations of femininity do not function as mere images isolated from their socio-political reality; they have historically served as catalysts for gendered metaphors. Religious and mythological symbols of femininity are important to consider because of their perceived ability to represent a power that human beings have interpreted as divine and unquestionable.

But as feminist theologian Isabel Gómez puts it, “un Dios descrito como varón se convierte en un varón Dios” (a God described as male becomes a man-God). Throughout history, the dissemination of androcentric symbology that attributes the creative power of life to a male God (together with the degradation of female symbols linked to power) has had a brutal impact on the shaping of our common imaginary. As kids, and later as adults, society is shaped by the symbolic world. The effects of this might seem abstract, but one can only become what one is able to imagine.

Guerrero aims to fill this gap in the imagination by continuously generating a new feminist symbology through the creation of the contemporary myths, vestiges and staged rituals. Together, these perform as windows into a raw matriarchal utopia that foster a sense of belonging. As paths through which the female millenary wound might be healed, Guerrero’s oeuvre brings the utopia closer to reality by presenting a series of poetically fabricated myths of a female past that has not existed, but makes space for the future.

Like a clash in the course of history, inside a space where multiple gazes intersect, we encounter the foundational moment of a woman staring at a woman, who’s staring at a woman, staring at a woman… in an eternal loop of shared consciousness. But, in reality, who is looking at whom? And from where?