On a Zoom call from his North London home in mid-September, the artist Mark Leckey is preparing for the opening of his latest exhibition at the Turner Contemporary in Margate. Opening in October and running until January 2024, Leckey is both the organiser of this group show and a participant, where he will unveil a new audio-visual work. While the gallery takes its name from the artist JMW Turner’s frequent visits to Margate in the early nineteenth century, Leckey’s name is synonymous with Turner in another art context: as the winner of the 2008 Turner Prize.

Born in Birkenhead in 1964 and having studied art at Newcastle Polytechnic in the late 1980s, Leckey emerged on the British art scene in the late 1990s, when his first video work, Fiorucci Made me Hardcore (1999) was exhibited at the ICA in London. Using footage of Northern Soul in the 1970s and acid ravers in the late 1980s, the work takes its name from the clothing brand popular with the football casuals of this same era. Like much of Leckey’s work with video, sculpture and installation since then, Fiorucci offered an examination of popular culture alongside issues such as identity and class in Britain from the late twentieth century onwards.

While the video has gained a cult-like status in the twenty-five years since it was made, Fiorucci was—from the view of the late 1990s—an examination of the notion of “nostalgia” at a time when Britpop was cultivating a longing for a bygone era. For Leckey, subcultures like Northern Soul and rave offered something progressive in a way that British culture of the mid-late 1990s did not.

Leckey’s use of archival footage in Fiorucci would anticipate how the internet would cultivate a sense of nostalgia on platforms like YouTube. Ironically, or perhaps aptly, there has been a yearning for precisely the rave culture that Leckey saw as progressive in Fiorucci; the comment sections of old rave videos on YouTube are full of people reminiscing about time spent at raves and for those too young to have been there, to long for its promises. In a way, then, the internet has become a space for collective and personal memory, which is a theme that Leckey explored in Dream English Kid 1964–1999 AD (2015), a video which looks back on the larger cultural hinterland of his youth and includes found footage of a 1979 Joy Division gig that he attended as a teenager at the fabled music venue, Eric’s Club in Liverpool.

As such, space is a central theme of Leckey’s work: consider the cultural resonance that a space like the Wigan Casino, a club at the heart of Northern Soul, holds, and that also features heavily in Fiorucci. These were shared spaces, where subcultures were forged, and identities shaped. Crucially, the spaces that feature in Leckey’s work are often outside of national cultural institutions. Though, as an artist, it is often in the latter that Leckey now examines the significance of the former.

For example, in 2019 the Tate Britain staged a solo exhibition of Leckey’s work, titled O’ Magic Power of Bleakness, for which he created a life-size replica of a motorway bridge from the M53 in Merseyside. It’s a bridge that Leckey knew growing up in the Wirral, but it also stands in for the kind of in-between spaces that kids gravitate towards in the absence of having access to other places to hang out in. The bridge also serves as the backdrop of a video work Leckey made for the exhibition, Under Under In (2019), in which a group of teenagers have a supernatural encounter there.

Since 2016, Leckey has hosted a monthly show on NTS, an internet radio station based out of Dalston in London. He plays his own music amongst bits and pieces that he has found and collected over the years: it is not a show that can be defined by a particular genre or period, but an eclectic mix of sounds that, much like the images and footage used in his visual work, speak to him. (Fittingly, NTS’s home on Gillett Square in Dalston has long been eyed up by developers eager to monetise every inch of the capital—the fact it is an established multicultural hub for Dalston’s diverse population deemed an inconvenience).

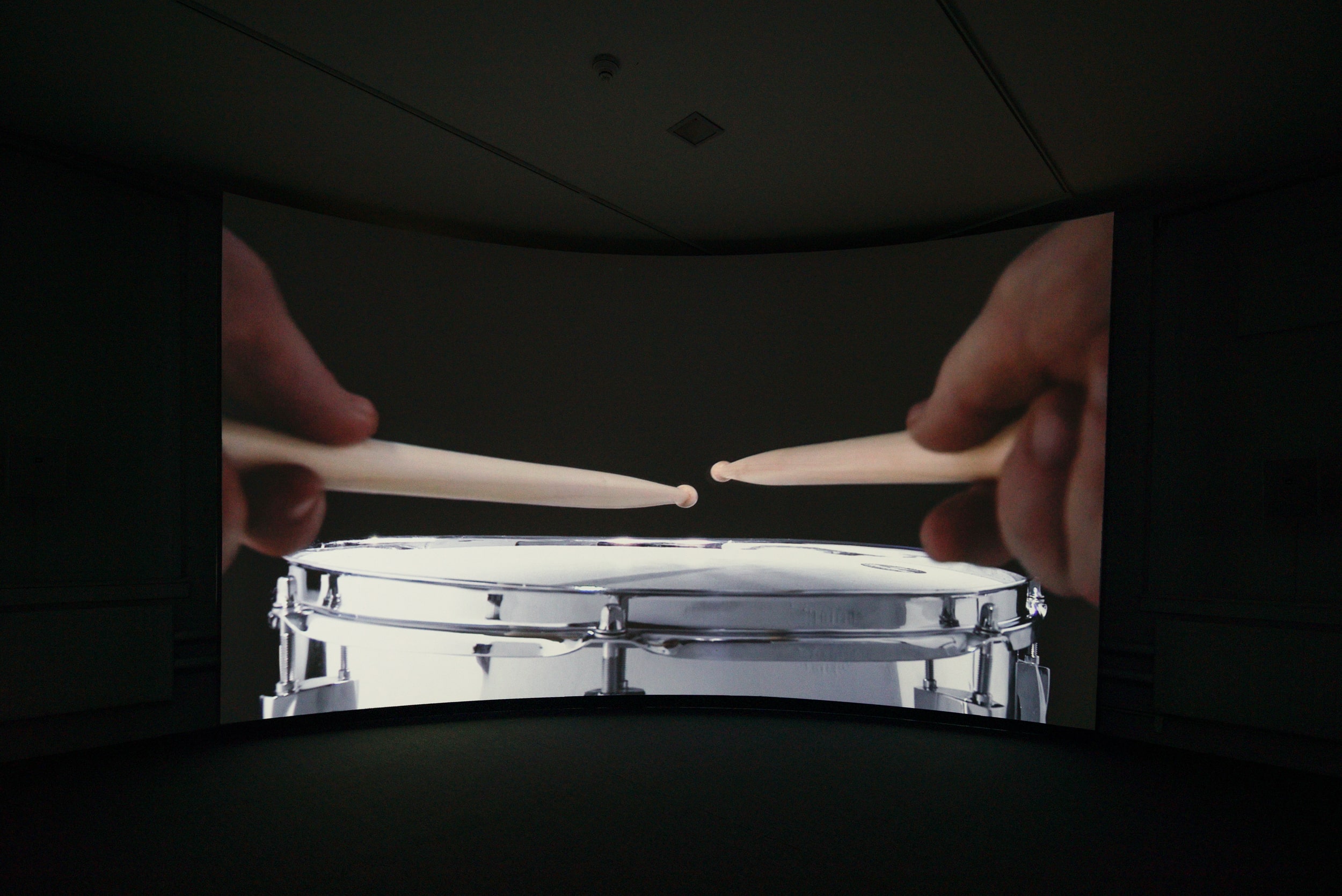

The NTS show informs the structure of In the Offing at the Turner Contemporary in that he approached the exhibition in a similar way to putting together a show for the radio station. “The way the show works,” Leckey says over Zoom, “is that it’s on a show system, which allows you to choreograph video and sound, so everything’s playing continuously and simultaneously without creating a cacophony of noise. So, things are going on and off, intermingling and intermixing.”

DAZZLEDDARK (2023), which Leckey made for the show, is in amongst this loop. “I play my stuff amongst everyone else’s, so it’s essentially the same as when I’m putting together a show for NTS, which over time I’ve come to enjoy maybe more than I do making art, so I wanted to see if I could transfer that enjoyment to putting on an exhibition.” As such, In the Offing looks to music as much as, if not more, than it does towards the art scene because Leckey explains, he was curious to see how they would respond “visually as well as sonically.” To that end, it is not only artists that feature in the exhibition but musicians, too – including rapper Blackhaine.

There is a site-specificity to In the Offing, in that it is an exhibition that examines the role of the Turner gallery in relation to Margate’s seafront promenade. The gallery is at one end of the promenade, while the nineteenth-century amusement park, Dreamland, is located at the other. While the Turner Contemporary opened in 2011 as part of a regeneration scheme in the town, Dreamland had fallen into decline by the end of the twentieth century and was saved from closure in the early 2000s. As such, these two spaces represent different forms of cultural investment. This dichotomy, between art and popular culture, is something that Leckey is ideally suited to examining. Ahead of the Turner exhibition, Leckey hosted a variety show at Dreamland’s Roller Room in December 2022.

“In the offing” is a seventeenth-century maritime term that is today used to refer to something that is on the horizon. In this way, Margate acts as a kind of microcosm for the seaside town in flux, as well as a site of exploration for the kind of collective memories that the seaside evokes. For Leckey, an early visit to Margate ahead of the exhibition “conjured up images of the seaside—I don’t know if they’re really there anymore—of palm reading and the clairvoyance.”

DAZZLEDDARK (2022) reckons with this. Looking towards the neon brilliance of Dreamland from a sandbank offshore, a unicorn plush toy (sold at the fairground in the film, and at the Turner Gallery shop in real life) and a merry-go-round horse are enthralled by the promises of the bright lights and the dizzying rides. The work is, by Leckey’s own admission, “very dark and noisy, it’s a sensory overload in some ways.” There is something sinister about DAZZLEDDARK—from its ominous soundtrack to eerie shots of the seashore at night. This is extended to the staging of In the Offing more generally, which Leckey describes as being like a dark ride at a fairground.

Leckey describes himself as the editor of In the Offing, rather than its curator, inviting the artists and musicians to respond to the title. For him, the notion of being “in the offing” can be seen as a meditation on the present state of things at a time when the future, in the arts but also more broadly, looks bleak. The artist is aware that his journey into the art world was very different from the one that the current generation faces. “I got such an easy passage,” he says, “I had youth clubs, I had a full grant, I got housing benefits. It was easy for me to go to art school and follow this path.”

Partly for that reason, Leckey’s exhibition at the Turner will coincide with a Music and Video Lab for young people organised by the Arts Education Exchange in Margate. It follows a similar Lab with the artist and musician Liam Jolly in 2022, in collaboration with the Cornwall- based arts education charity, CAST. Not long after his call with Present Space, Leckey was heading up to Liverpool, where he has worked with the Greenhouse Project: Young Event Producers to help young people from Toxteth create an audio-visual installation for Late at Tate Liverpool. The premise of these labs and workshops, Leckey says, is that they’re akin to a youth club for those who are interested in developing music and video editing skills. As much as his involvement with these initiatives is about giving a new generation access to the arts and music, it is also a week for Leckey to look out to the horizon and see what’s coming.

I knew the phrase as an idiom, but I didn’t know the origin of it. When a boat comes into the offing that means it’s coming towards you; it’s coming into the harbour. So, it’s this whole thing of moving towards the present, but also the idea of what happens when you look out into the offing? From the beginning, I knew that I had to commission young artists to make work for the show, and so I liked that they were in the offing. Maybe you could use that for artists, instead of saying “emerging” you could say they’re in the offing. I didn’t want to curate a show, so I thought I’d do it more like a magazine editorial and say, the title is the theme, and the work has to respond to that in some way. I thought that gives people an opportunity to look out and gaze at the future, to try and see beyond the dismal tide that it promises—or maybe you can’t see beyond that; maybe you’re completely immiserated in the dismal tide!

I think there is some conflict between art as spectacle and art as something more contemplative. With O’ Magic Power of Bleakness, I kept saying that I wasn’t trying to think of it as an exhibition, I was trying to think of it as an attraction. And then down in Margate, I found it really fascinating that on the seafront there are these two poles: there’s Dreamland, and then there’s the Turner. And in some ways, they’re irreconcilable; it’s a culture clash. So, I wanted to do a show that was more like an attraction than an exhibition and invoke Dreamland because I like places like that.

I don’t know if it’s become a bit of schtick now, and maybe I’ve exhausted it, but for a while, I’ve been thinking that the best way to make art is to deny it in some ways. And the more I move towards music, the more I can make art or generate ideas about art. Personally, if I think too much about what I’m doing then it just ends up inhibiting me. I become overly concerned with meaning and history, and the continuum of it just overwhelms me. I love music, so it’s a way to avoid that kind of self-imposed constriction. Music gives me permission, and ultimately, that’s just what you’re looking for in art—you’re looking for permission. So, the attraction idea behind In the Offing, also allows me to not be, again, encumbered by exhibition making.

In terms of DAZZLEDDARK, I wanted to make something that was an impression of the seaside and all the things that I feel or have felt, the strongest impulses and sensations I have when I’m at the seaside. So, I was trying not to make it nostalgic— and I don’t think it is—but it has seeped in there. It’s quite hard to go to the seaside and not be nostalgic; it’s a nostalgic place, right?

But also, in terms of what you’re talking about in relation to the home, I think the biggest generator of the work that I make is the sense that I lived one life that determined me, and then moved to another life, or another culture, that redetermined me in some ways. There’s a sort of resentment in some ways. When I first went to art school I thought, “This is culture.” And gradually I realised that I’d come from a place that had a culture of its own. But then, you know, I can’t go home. I don’t want to go back. So, I guess home for me is some sort of unresolved tension that I will never be entirely at peace with. I’d say it’s behind most of what I do; home for me in that sense is very much a part of why I make art.

We were talking about music before, and I was saying there are more musicians in this exhibition. And one of the reasons I’ve leaned into music or have been leaning into music is because, to me, music is the evidence of the intelligence of the working class. It’s like you just point to it, and say, “Look how sharp, creative, imaginative”—whatever word you want to bring to bear to the canon of art, it’s there in music that comes from the working class. When I first went to art school and entered a more middle-class culture, music was never seen as being equivalent, less so now, but definitely when I started at art school. Art was aspirational, music was—or the music I’m talking about, rave and stuff like that— was just seen as being kind of crass. But I always thought crass is clever! You can be very clever with crassness. So, I think In the Offing is going to be quite crass.

Massively. There’s a drive now within art institutions to reach local populations and be more inclusive. And I think that’s what music does and has been doing for a long time. What I’ve always loved about music is that you can have music that’s both local and completely experimental. Whereas with art, the process for me was that you had a kind of division between those two things, that you couldn’t be local and avant-garde. But you can because music demonstrates that.

I think I’ve spent too long denouncing art. Music introduced me to the esoteric, and then art allowed me to really investigate that. So, both of them have been equally positive [influences] in my life. I like trying to find the balance between the esoteric and the popular. That’s the one that rings my bell! And I think it’s doable, so I’m hoping the show in Margate gets somewhere towards approaching that.