For almost a decade, the architect, artist and designer Harry Nuriev has been quietly transforming the design industry. I say quietly – though Nuriev is pensive, if slightly jet-lagged, speaking via Zoom from his apartment in Paris – his vision is anything but quiet. Having founded his design firm Crosby Studios in 2014, Nuriev has worked with clients ranging from private residences to retail stores. He’s also collaborated with Balenciaga, designed a furniture line for cult New York brand, Opening Ceremony, and, at the time of our Zoom call, recently exhibited a collection of furniture made out of denim at the Carpenters Workshop Gallery in Paris.

Though Nuriev is, first and foremost, a designer of objects and spaces, he draws upon the fashion world for inspiration. Thus, the intention for his show in Paris was to translate elements of fashion onto the design world, using a fabric as conspicuous and versatile as denim to create a modular sofa, vanity desk and chair, and gym gear, amongst other household items. In some ways, the idea of approaching furniture design through a sartorial lens recalls Nuriev’s collaboration with Balenciaga for the Design Miami fair in 2019, for which the designer created a transparent L-shaped couch out of biodegradable vinyl which he stuffed with deadstock clothing from the French fashion house.

But while the collaboration with Balenciaga was part of an exploration into environmentally-conscious design, the concept for the Denim collection stemmed from Nuriev contemplating “how people live today” – a question that has been thrown into sharp relief in the aftermath of global lockdowns, in which citizens the world over had to adjust to living, working and staying at home. Even now, as the World Health Organisation has declared the coronavirus pandemic officially over, aspects of this new way of life have lingered on. As Nuriev points out, the fact that our interview is taking place via Zoom, with each of us dialling in from our homes, would have been a totally unlikely scenario four years ago.

So, Nuriev decided that rather than fight against the changes wrought by the pandemic he’d embrace them, “and create a collection that accommodates those needs; work, sleep, sit, party. You can do anything there, and it’s modular so you can readjust it. It has a workspace, it has a DJ booth.” In this sense, the collection was part of the designer’s ongoing investigation into how furniture can be reimagined and reinterpreted to create new functional ways of living.

In light of the Denim show at the Carpenters Workshop Gallery, I ask Nuriev what it means to share his pieces with gallery visitors, or at pop-ups like the temporary 3537 space in Paris run by Dover Street Market, where he designed all the furniture for the Crosby Café? Nuriev replies that he sees the value in sharing his work both in real life and digitally, through platforms like Instagram where he has a loyal following. While he values real experiences as crucial, describing himself as “old-fashioned [in that] spaces can really [enable you] to feel or think about things differently”, it’s through digital platforms that he is able to reach a bigger, global audience who want to engage with his work.

In the decade since Crosby Studios launched, the rise of the metaverse and Web3 has had a transformative impact on the design industry – something that Nuriev has taken in his stride. While he often shares renders online, many of his real-life designs look as if they could exist only in a metaspace. To see how far Nuriev has embraced the increasing influence of the digital on the “real”, contrast the purple hand-shaped lamp he made for the 2018 collaboration with Opening Ceremony with the more recent video game stools. While both capture the subversive playfulness that Nuriev employs as a designer, the stools really do look like pixelated sketches made on Windows Paint. It’s hard not to see how Nuriev has immersed his furniture design through a digital gaze.

And so, while it’s possible to see how far Nuriev has pushed his own conception of design over the past decade, this progression is also a reflection of how far the industry has embraced new trends, too. Through Crosby Studios, Nuriev has built up a base of clients who are prepared, and willing, to be pushed to the limit. “I push everyone out of their comfort zone,” Nuriev says; from the beginning of Crosby Studios, he told clients “not to be scared of colours, of open layouts, of furniture that can look like art and function like art.” But, Nuriev acknowledges, those clients were people who wanted this change, “people who asked me to push their boundaries.” These early adopters (and everyone since) are people who share an appreciation and understanding of the fact that Nuriev designs for the way that he, too, exists. “This is how I live. This is how I eat. This is how I sleep. For me this is very normal.”

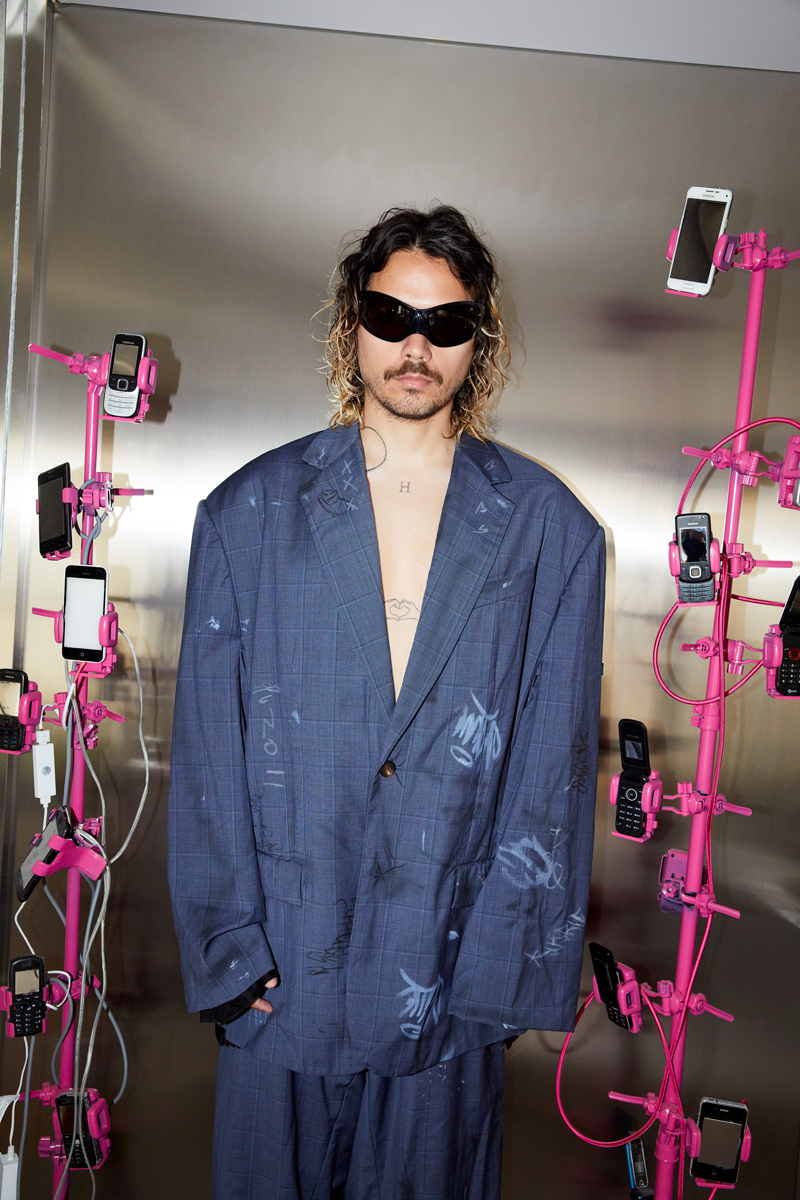

For the Present Space shoot, Nuriev is photographed in his apartment in Paris. While Nuriev has retained some of the features that capture the essence of Parisian apartment living, such as the building’s original wood parquet flooring, he’s also constructed what he describes as a “stainless steel capsule” for a bedroom. It’s from here that Nuriev wakes each morning, abiding to a mantra he’s lived by since he started out, “every morning when I wake up, I want to see the world change and be part of that change.”

I put it to Nuriev that one of the legacies of his work to date is that colours such as neon green, that may have had something of a shock factor a few years ago, are much more commonplace. While Nuriev acknowledges that much is the case, he demurs that his work is about shocking people. “I don’t care if they’re shocked, and I don’t think they’re shocked.” Rather, he says, people are drawn to things that look and feel nice. That’s certainly a truism, and reminds of the myth (because, apparently it turns out, it is a myth) that magpies hoard shiny things.

But – as if proving that myth correct (or at least, providing a neat metaphor) – Nuriev has turned to using silver as a material for recent interior design projects besides his stainless steel capsule bedroom. In fact, one of his first experiments with silver was at his previous apartment in New York (where Nuriev lived from 2016 until his move to Paris two years ago). There, he decorated the kitchen with leather silver cabinets. That apartment was featured in The New York Times in 2020, in which Nuriev’s soft-fronted kitchen cabinets were photographed with a subtle purple sheen reflected off their surface – an effect achieved by light shining through a purple plexiglass panel dividing the kitchen from the rest of the apartment. Some comments on that article were, as might be expected, critical of such a design choice – this is not something that seems to phase Nuriev however.

“I’ve been working for almost five years to prove that silver is not a cold, medical material. It’s just a very beautiful grey colour that reflects everything around you. It’s not cold – why do you think it’s cold?” Nuriev asks. “Yes, it’s cold in a sense,” he continues, “but it can be warm too.” He queries the kind of cultural attachment associated with certain colours: that metal equates sterile environments, that pink is for a girl’s room (a concept attributed to retailers divided kids’ clothing and toys in order to double the size of the market in the twentieth century), and that Klein blue is art. That kind of Klein blue is one Nuriev has previously appropriated for his design vision: a ultramarine blue powder-coated kitchen in a previous apartment the designer lived in (before the silver-cabineted apartment) is evidence of such.

Nuriev summarises his role as one of exploration. “That’s my job, it’s nothing else. And if I bring colour and silver to the design industry, I’ll be happy.” Arguably, Nuriev has already done that; before the neon green and the blue, he was filling interiors with bubblegum pink before millennial pink became the colour of choice for marketers trying to reach an impressionable Instagram audience. Perhaps that’s what makes silver such an alluring choice now: it quite literally reflects the industry’s excited embrace of colour back on itself.

It’s not Nuriev’s intention to see homes the world over converted into identikit stainless steel pods. Nor is he dismissive of others’ tastes. Part of the beauty of design, he says, is that “we all want different things. Maybe someone has had a pink sofa for many years, and now they want a beige sofa… Maybe I’ll want a beige sofa,” he muses. Though, for the record, Nuriev says he’s not as concerned with honing in on one colour as the source of monochrome designs now. “I’m not about colours, or just about this, or that. I’m about transforming things.”

This notion of transformation is something that Nuriev elaborated on in an Instagram post from late 2023, in which he shared that he was using the term “transformism” as a label to describe his work where other, existing -isms don’t quite fit. (You can buy a denim cushion from his collection for the Carpenters Workshop Gallery that brandishes the term.) Transformism, then, stems from Nuriev’s approach of taking something and using it – literally, or as a source of inspiration – for a different end. While, to date, Nuriev has used materials like denim or everyday objects such as iPhones (reworked to form a Crosby Studios christmas tree), he mentions that he’s also been looking back into the history of architecture and design for inspiration.

The Gothic period, for instance, is something Nuriev mentions during our call. In particular, Nuriev mentions tapestry as an innovative and beautiful technique that doesn’t play much of a role in interior design today. “It’s like the first version of the pixelated screen,” he suggests, “because each thread is only one colour, and so each stitch is like one pixelated colour.” It’s an intriguing insight into how Nuriev’s eye for design works. For sure, the designer states that he is always looking for the next thing, as a way to avoid getting stuck into the same thing. But it also shows how Nuriev intuitively sees the potential in something to become a coveted object in an interior setting.

Though Nuriev draws on endless sources of inspiration when it comes to conceptualising his brand of design, one of the discussion points that pops up again and again during our call is how important clients and collaborators are for his practice. Nuriev may be the tastemaker, but the support and engagement of people help differentiate between ideas on paper or on the screen, and fully-realised projects. For recent examples of how he brings his vision for silver as a warm material to life, see the Crosby Studios-designed Amina Muaddi store at Harrods, or the collaborative We Are Ona pop-up restaurant that opened for a week in New York in May 2023.

When it comes to the Crosby Studios client, Nuriev says there is no particular kind of person that is drawn to what he does. We bounce words back and forth for a while, trying to find a word that might define a quality or an essence to Nuriev’s clients, before he eventually suggests that, “maybe the word is curiosity.” Yes, he says, it’s curiosity that neatly captures what draws people into his world of design.

While Nuriev continues to share this world with an engaged Instagram audience (with each post met with a stream of gushing heart-eyed emojis), he’s also created a more manual record of his work. In late April, Nuriev released his first monograph: How to Land in the Metaverse: From Interior Design to the Future of Design, published by Rizzoli. Nuriev describes the book as straddling both the metaverse and the real world. “Half the book is about virtual projects and [the other focuses on] real projects.” While this crossover stems from Nuriev’s engagement with both kinds of projects, he mentions that the book also sets out to clarify the distinctions between the two – especially for people who can’t always tell what is real and what is not.

Nuriev notes that some of the first projects he worked on were, in a way, the first iteration of the virtual projects he now creates; these “paper architecture” projects are not so dissimilar from digitally-rendered metaspaces. The difference though is that, where the term “paper architecture” has often been used as a snide way to describe projects deemed too unrealistic or too ambitious, it is precisely those characteristics that make virtual architecture so alluring today. While How to Land in the Metaverse will grapple with the overlaps between the two realms of design, it is also a chance to flick through a decade worth of Nuriev’s work – an opportunity to “share the evolution of my design and the evolution of Crosby Studio.” With the publication of Nuriev’s first monograph bound with a hardback silver cover, it’s hard not to feel that silver is undoubtedly the designer’s “colour” de jour.