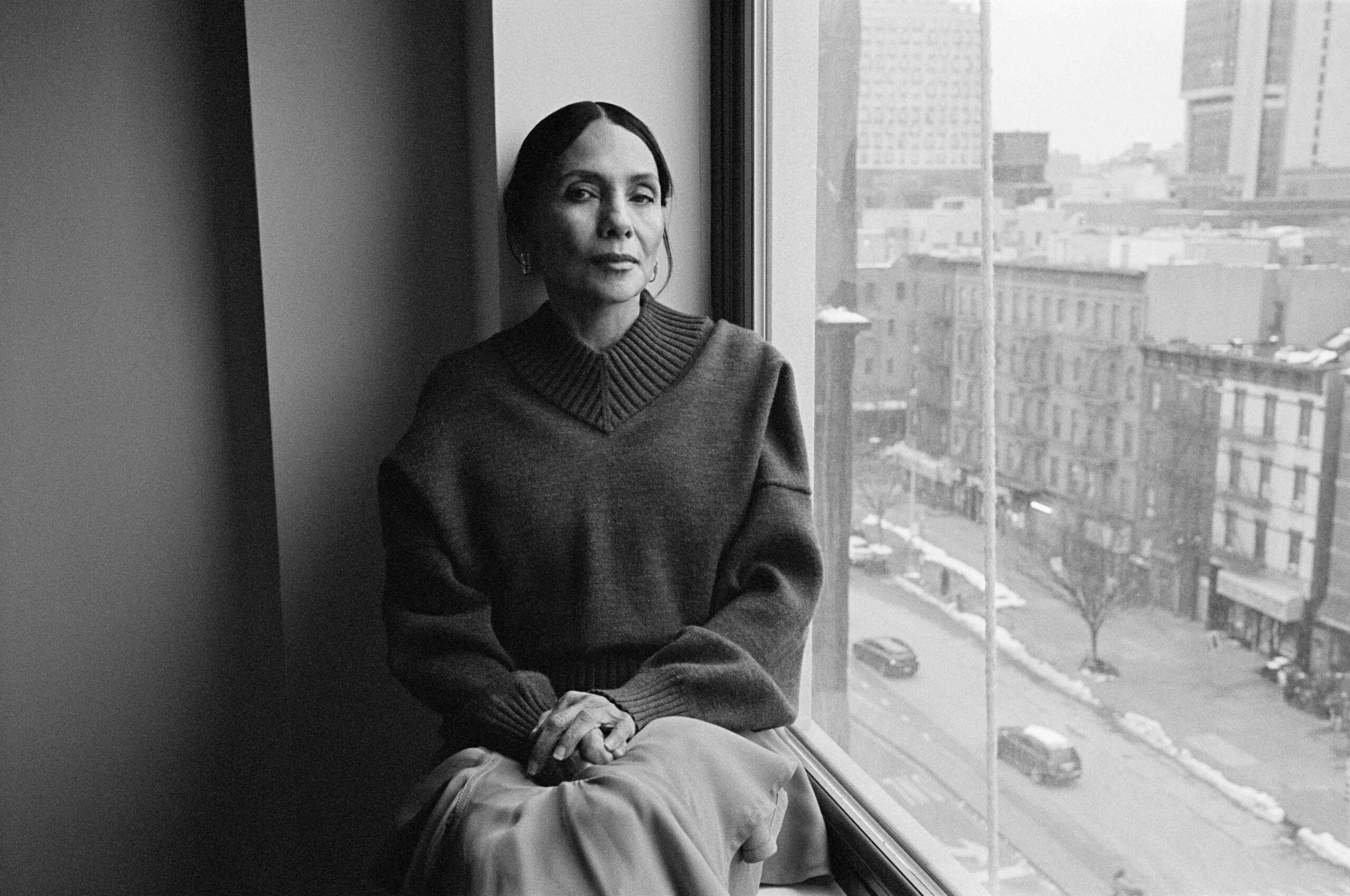

One a filmmaker inspired by photography and the other a photographer inspired by film, it seems fitting that Melina Matsoukas and Ming Smith’s lives should be cosmically intertwined, as if “ships [passing] in the night.”

Clearly enamoured by her subject, filmmaker Melina Matsoukas interviews photographer Ming Smith, who is joined on their call by her son, Mingus. Reflecting on the theme of ‘genesis,’ the pair quickly bond over the work of mutual friends such as Mickalene Thomas and Arthur Jafa, speaking highly of the divinity of their collaborators, contemporaries and shared people.

The daughter of a pharmacist who was himself an artist and photographer, Smith grew up in Detroit, Michigan before attending Howard University in Washington, D.C., where she studied microbiology and took the University’s only photography class. Moving to New York in the early 1970s, she soon found work as a model. Visiting the photography studios of Anthony Barboza, Lewis Draper and Joe Crawford and later attending the dance classes of Alvin Ailey, Katherine Dunham and Syvilla Fort, in 1972 she became the first female member of The Kamoinge Workshop: a collective of Black photographers who gathered weekly to critique and review each others work.

Reminding her audience that “the Black man and woman were the first people on the planet and had the first high civilisation that dealt with spirituality and reciprocity,” prompted by Matsoukas’ thoughtful questioning, Smith discusses a life surrounded by sophisticated artists. Referring to legendary Black cultural figures such as Alvin Ailey, Grace Jones, James Baldwin, Romare Bearden and Sun Ra as either personal friends, subjects or both—and with Matsoukas counting contemporary figures such as Beyoncé, Rihanna, Daniel Kaluuya, Jodie Turner-Smith and Issa Rae as amongst her own subjects—it is perhaps surprising that the pair appear to be equally, if not more so, endeared by Smith’s anecdotes about the quotidian idiosyncrasies and genius of everyday characters, from a bricklayer she encountered as a young child to a little girl she recently bonded with over “a cute little purse [with] little butterflies on it.”

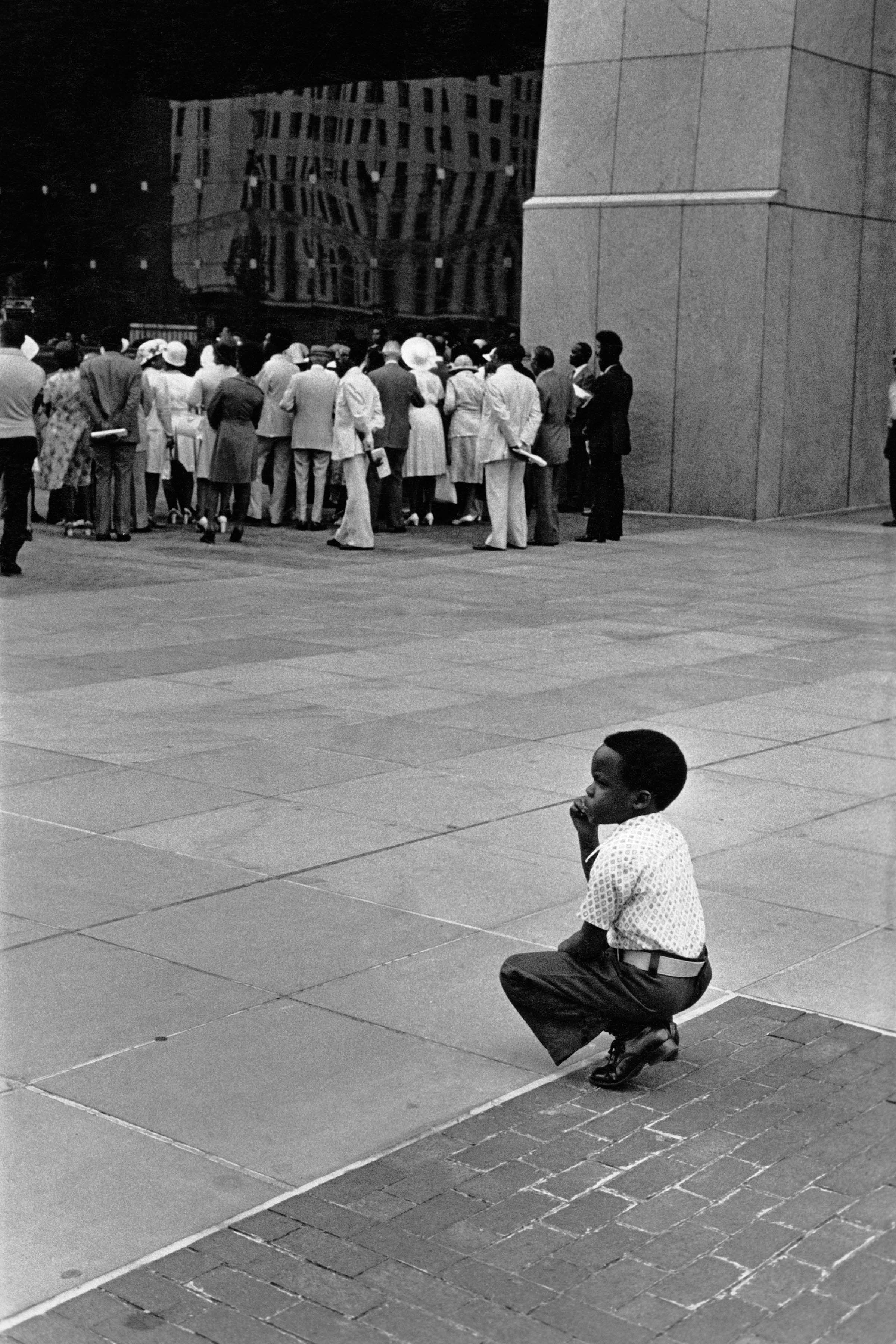

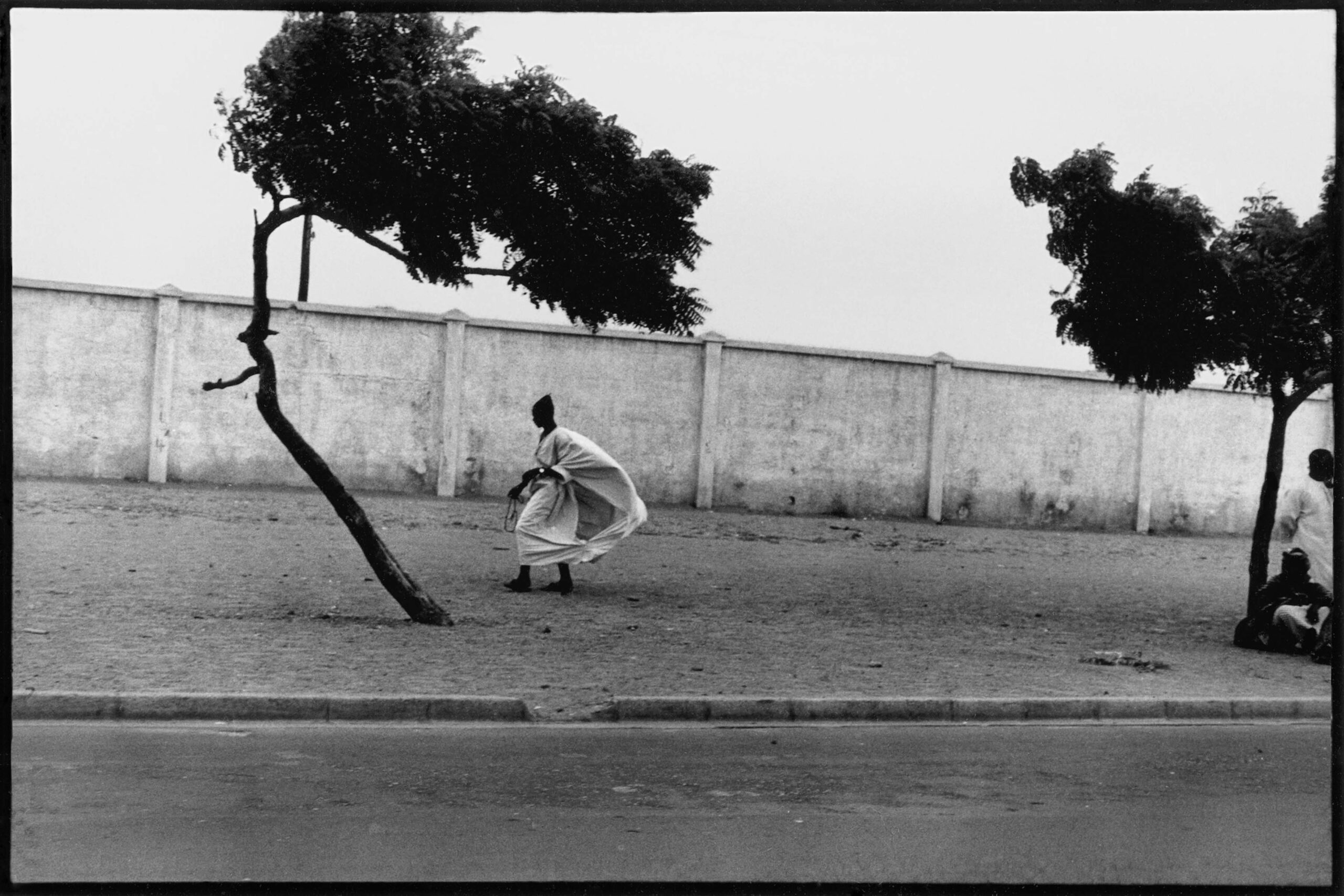

Finding divinity and grace in scenes of struggle and survival, Smith’s black-and-white photographs employ surrealist techniques to create dreamlike and ethereal imagery, embodying within them “a sacred, poetic intent.” The first Black female photographer to have her work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), recognition of her work has risen in recent years with thanks to several high-profile exhibitions: including Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography (2010) at the MoMA, We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85 (2017) at the Brooklyn Museum and Going Dark: The Edge of Visibility (2023) at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, as well as Arthur Jafa: A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions (2017) at the Serpentine Gallery and Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power (2017) at the Tate Modern in London.

Acknowledging the “remarkable, frightening, profound, barbaric and divine things” currently approaching the global community, Matsoukas and Smith close their interview with the exchange of information, requests to see more of each others work and the warmth of inevitable friends.

Hello

Thank you, thank you.

Well, thank you so much. I really appreciate that.

Oh, that’s great. I love that. Especially, I love Mickalene too.

She really is, I love her.

Yes, yes—definitely!

Sure.

I was inspired by cinema. Something about it shook me to my core and shaped my eye, how light and darkness can shape beauty and tell a story poetically.

That was hard, math. [Both laugh].

Did you have plans to go to med school?

And you took those hard courses? [Both laugh].

Well, I was around so many sophisticated artists—many were black, some were white. During that time, people didn’t have shows like they do now so people set out to have a real authentic voice, and that’s what I loved about New York. I loved all of the creatives. It was just wonderful to me, it was a new world I had discovered. Their stories were authentic and people brought their culture with them. It was raw and new. There was complexity and integrity in the art world. You had so many diverse characters; it was like watching a movie. They had their idiosyncrasies and genius. A prime example of that was Grace Jones, a lot of people didn’t get her. Or the hairdresser Cinandre who was from Belgium. He was the first one to put colour in the hair. You know, he cut her flat-top? He was the first one to do that. He was also the first one to cut my hair. I used to wear my hair—not for ads, but for different things—curly but for jobs they wanted it straight or in a bun or even an Afro.

And it was in-between the curls. So, he advised me to wear it like that—natural—and that’s how I started wearing my hair like that for ads and things.

My hair was naturally like that and then it became a trend. All the top models were getting these perms and they were ruining their hair. He said, ‘Don’t tell them, just tell them that you got your hair done at Cinandre’s!’ [Both laugh]. It helped his business.

Well, as you know, Kamoinge was a Black photography collective founded in 1963 and it emerged as a shared political and artistic space for photographic improvement and self-determination. I never felt like the only [woman]. It was bigger than me, it was like being part of a people that wanted to change things. It was political and visual—and that was the biggest draw.

I don’t know. I was a certain point of view—not only being Black, but being a [woman]. And so, most definitely that was the intention, to break away from those.

It was most important but I always approached photography through myself. I wanted to be authentic and I wasn’t always thinking—as is the way today—this is a woman’s point of view. I am a woman, and it just came out of that. Being authentic and creating something that was like poetry or something that was beautiful, that was my goal as a photographer. But, even with the Kamoinge, I didn’t think of myself as the only woman because we were always thinking about what we wanted to do, how we wanted to change things… Actually, it was a safe place for me.

Well, if I would go to the grocery store or walk down the street some guys would always come on to me. But there, because that purity that was intention was there, it was bigger than me. It was really bigger than anyone. It was a group that wanted to change the world, basically. We were being revolutionary on our own terms. And this is why I always liked Angela Davis. I wanted to be her. [Both laugh]. I have hair all crazy like that, but it didn’t stand exactly the same way.

I tried all kinds of things; I even wore an afro wig. But I learnt about existentialism because she was really into philosophy, and all of that.

Well, I focus on breathing when I shoot. So, the action is what you are describing and it comes out in different narratives: microcosms of beginning, middle and end. It’s a frequency and a rhythm, and it’s right there in the moment. In photography, that moment can never be repeated but that moment has the genetic imprint, frozen in time with the start of a beginning and an end.

For me, it’s about being in the moment. The subject’s history, the lighting, the setting—everything converges to create a sacred, poetic intent. My goal is to capture that moment and freeze it in time to convey the beauty and essence that I see.

Yes, I see Black people as spiritual beings and children of God because the Black man and woman were the first people on the planet and had the first high civilisation that dealt with spirituality and reciprocity. I see God in all people, even ones that are not spiritually developed. It’s all part of the human experience. And usually, when I shoot someone and the image comes out as spiritual, that’s how they are in their own lives and I was attracted to their essence, creatively.

When I was a kid, I remember seeing this guy. He was a bricklayer in a yard and he looked like—I hate to say this but he looked like a bum. He was dressed in jeans and run-down shoes and he had a pint of liquor in his pocket. But he was a master mason so you couldn’t really judge him, and he had all these folklore stories. My brothers caught this possum in the garage but it became like a pet. And then one day, as he was ending the job—he had worked maybe a month, off and on, of Saturdays—my brothers went to see the possum and he was like, ‘Well, I cooked him last night!’ or something. And we were like, ‘Oh my God!’ So, I was always fascinated by characters like that. They were so rich to me because of the experiences and understanding they had. And actually, that is why I was so attracted to August Wilson’s plays—because of the richness of his characters. He just wrote about the people around him. That’s why I did an entire portfolio going to Pittsburgh, I was like, ‘Oh, I know those characters! I know those everyday folk.’ There was so much beauty.

It’s one thing; cinema is basically just about story and about repetition of images. That’s what film is—it’s stills running its course.

I really appreciate that. You know, I love my work as well—and I love being an artist. I think that it comes through in my art and I hope people are inspired to dream and know that we are divine.

The complexities and isolations of Katherine Dunham really shaped my artistry. It sharpened my eye to the possibility of movements and subconsciously it comes out in my work. With dance you always look in the mirror and try to get things right, asking ‘Which is the most beautiful line?’ It allowed me to see and be comfortable with abstraction and the possibility of frantic movements that appear still. Or with music it can be avant-garde but it still has a Western harmonisation. Everyone who was a Dunham dancer did ballet, but she put her take on it. There were just so many possibilities in the medium. And just having the strength to do it. I mean, we are talking about lines, but Katherine Dunham, who she was—she was force. During the Vietnam War, she would fast, she would go on hunger strikes. And even with the health foods and things like that—she was a visionary. I attended one of her masterclasses at East St. Louis and what did she start out with? Yoga positions. And she taught us about the chakras…

It’s interesting because when I first found out about Katherine Dunham I was going to buy snacks for Kamoinge. I heard this drumming and I was like, ‘Wow!’ And see, I’ve always loved dance and I would always say if I came back I would be a dancer. She inspired Alvin Ailey. And, in fact, after seeing the Alvin Ailey exhibition [at the Whitney]—my whole life was right there, all the music, the people that I knew, the dancing. It was like an autobiography. I mean, I could go on because my friends were mainly dancers, not so much photographers and visual artists. I knew a few but I really kind of lived in the dance world because I was always taking classes, and I still dance.

Oh, yes—I dance. It’s the way I keep my sanity, literally.

I do Sabar and Cuban dancing.

Oh, you are? I had a friend who was an art historian and he was into the culture and he told me about how, when he was young, people would drop their kids at the Apollo and they would watch the dance troops and all the acts. It was just something that people did. Or after Church, how his whole family would go to the Apollo. Anyway, he had all these old stories and I love storytellers. He wasn’t a writer or anything but he knew about it and—all this to say—he always used to say, ‘A Cuban and a Southern person, if they have a child that’s the best combination you can get!’ So anyway, you’re Cuban. Are both your parents Cuban?

That Cuban—there’s definitely something in the Cubans! That’s what he said. [Laughs].

That’s why you are who you are.

No, I want to go there. In fact, my son went there a few times…because his father is a musician. My ex, my son’s father—that’s how I refer to him. I didn’t because, you know, we had broken up…

Yes, I’ve got to go. I want to do some film there, too. I’m really interested in the dance part. I mean, all of it—but visually, I don’t know. I’ll have to see because I don’t like to repeat, but everyone says just go and shoot and don’t worry about repeating.

Oh, yes—especially dance because they have dance conferences and all kinds of things!

That’s one thing. It’s very balletic, and I was never that good at ballet. In fact, I couldn’t stand ballet. It hurt too much. Not because I didn’t love the beauty—you know, [Mikhail] Baryshnikov and going to see all these different dancers—but the pain, my legs! You had to be so still. I was always trying to push to get that but I could never do it, all the classes in the world. It was interesting because when I would ask them, all my family, their legs would be like that naturally. They didn’t have to do anything, all they had to do was to build the muscle to enforce it. I was like, ‘Why me, of all people?’ [Laughs].

It’s the study of the lines.

Yes, it’s the interchange.

I just look for all the elements. In your filmmaking, when the light—but see, well now you have people who do the light—but naturally when you are shooting things without lighting, and even now in film when you have to shoot fillers, you learn how to play with the light, the movement, and then you also have dialogue. The great filmmakers, that’s what their art was…having that understanding and doing that dance.

I hear a collaboration brewing! [All laugh].

How are you?

I’ve loved your work throughout the years. I mean [Ming]’s seen your work too and she was like, ‘Who’s that, who’s that?’…

I’m so very much in the moment. It’s interesting that you say that because many times I’m working, mainly visually, and I see all the elements and I’m like, ‘Oh, I see the light! I love the way it’s hitting them.’ I grab my camera and sometimes you can miss it, that’s why the term ‘shoot.’ But then, many times afterwards—I’m sure this has probably happened to you in your film as well—you’re like, ‘Oh, this is much better than I even thought!’ As a photographer, even in the beginning, I was like, ‘What if you took a photograph and that wasn’t really the intent but it ends up being a better photograph than you even intended?’ But then people say, ‘No, but you recognised it. You saw it on the contact sheet so that is your work.’ So, it’s not just always the shooting; it’s the editing, it’s everything, right?

I don’t think about my voice. It’s basically that my life is representative of my voice—so whatever period I was in. In the early 1970s, I wanted to change some of the images of the stereotypes of Black people. So, let’s say Harlem. Harlem was a community that had all these stereotypes. With Mother and Child (1977), the woman on the telephone [with] her child, you could tell that she was in distress but the girl clings to her. People see just the poverty but they don’t see the love there between the mother and the child. And even in Family Free Time in the Park (1982), I was going to a concert in Atlanta and I saw this family. They were in a park and it was this beautiful image. It was the father, the mother—they were swinging—and then three kids. But the way the trees were…I was like, ‘Oh, I have to take this image!’ But see, I had just read this sensationalist story about how there were no fathers and all these [little boys] were being abducted. I was appalled by them saying these young Black boys were being abducted because there are no fathers in the home. And I was like, ‘They’re talking more about there being no fathers in the home than the boys being abducted!’ That pissed me off so when I saw that image I stopped and went and took [it] because I was visiting. That was what was happening at that time. When the Million Youth March was happening in Harlem, that interested me so I went and shot that. So, all of it was representative of my time. In fact, sometimes when people see an image they’re like, ‘Well, where were you in August 2005?’ I can’t remember things by dates but when I see the picture I can remember. Some people are different, they say ‘Oh, yes. We met in March 1990…’

Yes, exactly! So, that wasn’t really a planned thing but as my life evolves my interests change with it.

Well, I wouldn’t say it changed my eye but it changed my energy. I had to learn to be more patient. [Both laugh]. That was one of the main things. But I don’t know, I don’t really think so. Like I took this image—I guess it was in New Jersey—of this woman and she’s holding her baby and she has the shirt ‘I have a dream.’ I love that image but I would have taken it even if I hadn’t been a mother. I think with motherhood, or just being a mother, you think a little bit more about your legacy and that becomes important to you because you realise your work is going to affect generations to come and you want to make sure that it’s coming from an authentic place that will make the world better. And the way you travel through motherhood, you’re going to be more aware of things, you know? You might have to go to do something else, even though your work is there. Like I would do my work in between things.

Do you have a boy or a girl?

A girl? Aww, that’s so sweet—I’m into little girls now. I start talking to them and bonding with them. I want to have a little granddaughter. I saw this little girl and she had a cute little purse and it had little butterflies on it. I mean, I would have had that purse if I was a kid. It was the best purse, really! I kept on looking at this purse and this little girl and we became friends so I said to her, ‘Oh, I wish I had a purse like that.’ And she said to me, ‘You could make one!’ I was like, ‘That’s a great idea.’ And then I said, ‘Where did you get your purse?’ And she said from her grandma. But anyway—how old is your daughter?

Oh, wow! I also saw this woman and she had two girls…and I asked them their ages. The kid took off her shoes. She was on the train, she was barefoot, and I thought, ‘Oh my God, I couldn’t do this again!’ It’s too much. But the mother, she was so happy—and it showed in the little girl, it really did.

I know! She took her shoes off and before [her mother] knew it she had moved so quickly…

Hopefully you don’t have to get on the subway with your daughter. [Both laugh].

Let’s see. I had a Moneta Sleet [Jr]. He worked for Ebony magazine and he called up and said he wanted one of my photographs. And I was like, ‘Oh, what an honour!’ Because he shot this famous photograph of Coretta Scott King with Yolanda at the funeral. And then he also shot Billie Holiday, who then was my favourite singer and she had these pot marks… I’m just telling you the ones I asked for so I said, ‘Well, let’s just do an exchange.’ So I had two of his pieces. And then I had a Romare Bearden… I didn’t have a lot of money. I think it was less than $1000, but it was all the money I had, literally. And I was even paying with some pennies and he was like, ‘Oh, don’t worry!’ He had three pieces and he said, ‘You choose the one.’ And so, we became friends. In fact, he invited me to Martinique after I was married because he liked jazz and everything. And then I had a Gordon Parks that I bought… This was way in the 1970s and I just had money and it wasn’t expensive—but I’m not really what you would call a collector.

Actually, those pieces I ended up selling because I needed money when I was in LA during my divorce and it was either these pieces or my own career and survival so I ended up selling those pieces, happily selling those pieces. But I know who has them: these big collectors in New York, they got them really cheap! At least in the past, [as artists] you would rarely buy other peoples work—unless you were really rich—but you would do exchanges.

So as far as visual artists, I love Lorraine Hansberry and Romare Bearden. I love David Hammons…and Phyllis Harmon and just people that I knew. Alvin Ailey, I loved Alvin Ailey—just seeing him walking down the street.

Yes, I would see him just walking down the street going to Vogue. Oh, so—I have to tell you this one thing. When I first went to Paris, it was with someone who was with the Ailey company. It was their first season in the company and they were going to Paris and I was modelling so I was like, ’Oh, well I’m going to go too!’ Because I kind of had this crush on this guy. And I just remembered this because they had an Alvin Ailey exhibition at the Whitney. So anyway, he said, ‘We’re having a rehearsal.’ I came in and there was Alvin Ailey in the Josefine Baker auditorium and so I went right in and sat next to him. [Laughs]. But you know, he was still struggling then because I remember I followed him to different schools and locations. And there was another teacher, Henry LeTang, who did tap and he taught Savion [Glover] and Gregory Hines, who [was in] The Cotton Club so he was a famous person. I followed them and the reason I’m telling you this is because I guess he couldn’t pay his rent so he had another location and was always moving places. Alvin Ailey was the same but he finally got the school and everything else was history. But there were other people too: Elio Pomare and other artists that were around. Alvin was one that was successful but I knew of all of them so I sat next to him and that’s when I first met Judith Jamison and Sarita [Allen]—she had danced the longest. These were really beautiful, beautiful dancers.

Things that relate to a global consciousness. There’s so many remarkable, frightening, profound, barbaric and divine things approaching us as a global community. I want to deal with the subject matter as a human race in photographic collage form in stills and film.

Well, someone had said they wanted to do a documentary on me—a few people had asked me to do a documentary, actually—but you have to be kind of wide open and I don’t really like to talk about negative things that happened in my life. I really don’t, but I like this one. We’re still in the beginning [stages] of ‘Do I really want to go here?’ but it gives me the freedom to further my work only with me being the subject matter, visually. So, I said I would do it because of that.

Well, I’ll give them your name. [Laughs]. I don’t know, I don’t want to call the people that I know. I just want to call people that I work with—it’s organic, like right now.

Well, you could always send me some of your work. I’d like to see some of your films.

Okay, great—I would love that! Thank you for the interview.

What are you working on now?

I love that.

Have you worked with [Arthur Jafa]?

Wow, that’s beautiful!

Yes, I’m right on [redacted].

Oh, okay—so if you do, let me know! I know a few people that do real estate in Harlem.

That’s just up from me!

Oh, I’ve been here for 20-something years but before I lived in Laurel Canyon in Los Angeles. I was there for 12 years.

We switched positions. [Both laugh].

You know, I have a little short film—10 minutes or something—that my son Mingus and I did. He did the music because he’s a musician and it was shown at the CAM. I shot the images of the people that we used for the film and then we put it together.

I don’t know where it is. [To Mingus] The little 10 minute film we did for CAM?

Is it there now? I saw you were just in Spelman.

Yes, please. Please send me all your info so I have it.

Well, thank you so much again for everything. I appreciate you and your eye and the beauty that you bring to the world—and your energy is also just so incredible.

It was so wonderful talking to you and wonderful to meet you too, Mingus. Thank you, talk soon.