In 2019 Juana Burga founded Nuna Awaq, a foundation that aims to raise awareness of, and promote, the cultural significance of traditional weaving and artisanal craft of her home country, Peru. A model and actress based in New York for the past fifteen years, Burga embarked upon launching the platform to act as a go-between for two realms she knows: the fashion industry—and its notorious ability to appropriate culturally important garments and motifs—and the rich heritage of Peruvian artisans.

Nuna Awaq—meaning “soul of the artisan” in Quechua—seeks to empower artisans and textile workers by advocating for fair trade practices, supporting sustainable production, and ensuring that workers receive recognition and compensation for their work. In particular, the foundation works with different Indigenous Peoples in Peru where these ancestral traditions continue.

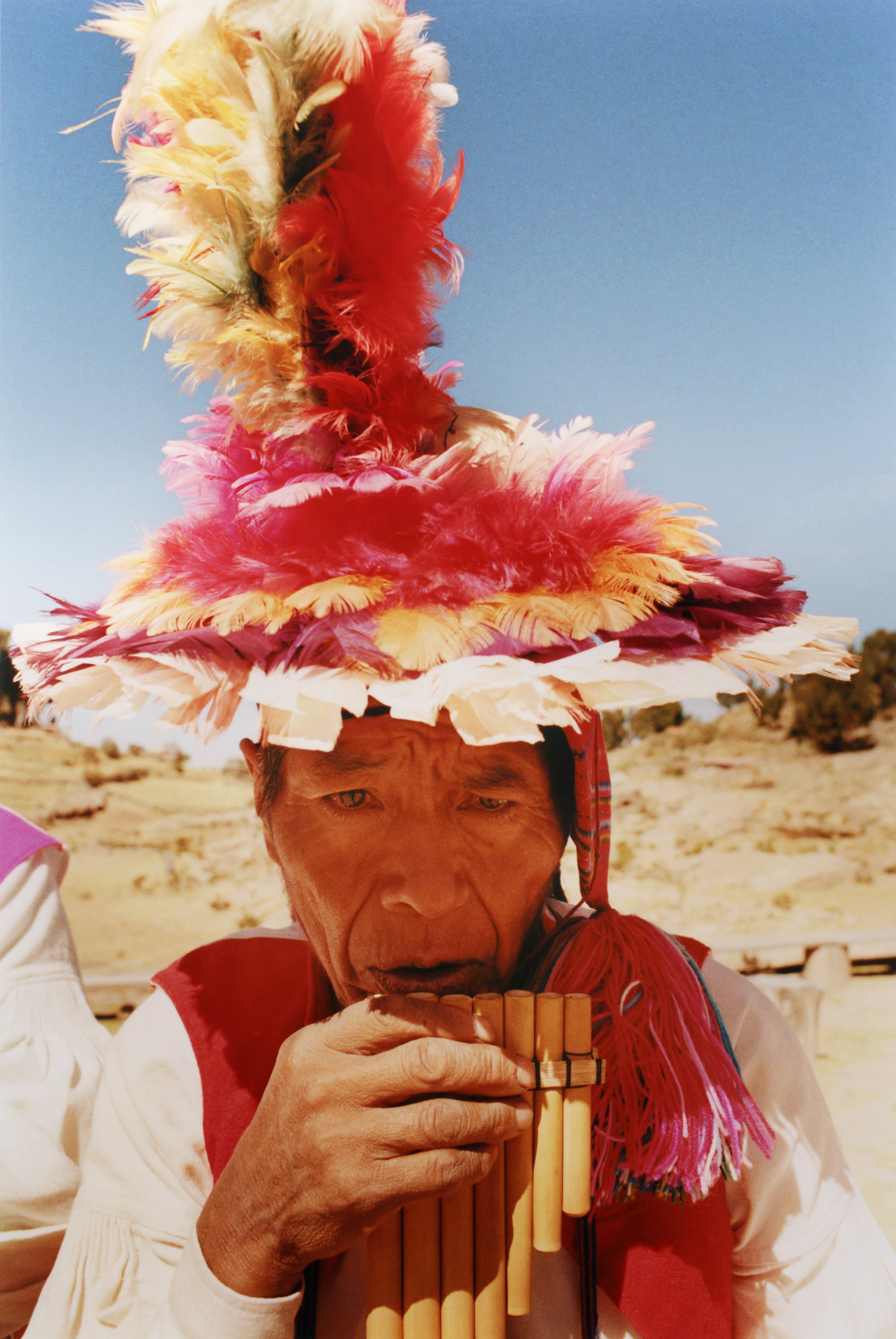

In June this year, photographer Diego Vourakis travelled to southeastern Peru, to spend time with different Indigenous communities. Though the Huilloc, Chinchero and Taquileños peoples all have their own traditions, all have a rich textile heritage dating back centuries.

There are long histories of textile and weaving practices amongst these communities, with techniques rooted firmly in tradition. Weaving is also deeply rooted in cultural and social tradition more generally; as Burga explains, the artisan’s craft requires extensive time and care to undertake. In that sense—and as the meaning of Nuna Awaq suggests—each piece of woven material or crafted item, contains a part of its creator’s “soul”.

The Chinchero and Huilloc communities both continue to use ancestral methods of working with textiles. Everything is handcrafted, using practices that date back to the Inca period. Vivid red wool and alpaca yarn, used for hats and other garments, gets its colour from a small insect called the cochineal, which is collected from cacti that grow in the region and, when crushed, is used to create a dye.

These weaving traditions have come under threat, much like the communities and environments of Indigenous Peoples themselves: the fashion industry has, at times, been culpable of appropriating traditional garments for shoots and collections. This is something that, through Nuna Awaq, Burga seeks to change. “[People] don’t [always] know the traditions [behind] these communities,” she explains: artisanal craft can be mistaken—intentionally or otherwise—as something “trendy”, or “fashionable” on account of the rich colours, motifs and styles of garments.

But, Burga argues, “for the artisan, everything—how they dress, what they wear, what they use—is necessary for how they inhabit specific geographic spaces.” The importance of having a connection to place (especially a connection that is rooted in ancestral heritage) is something that is also threatened by modern society. Indigenous Peoples continue to be displaced by mining operations—their land seized for industrial-scale resource extraction. This displacement not only disrupts how Indigenous communities live, it also has a detrimental effect on the environment of these lands: affecting water supplies and the quality of those fibrous lands upon which many communities have historically depended.

These issues are not isolated; they reflect global patterns where small, artisanal communities are often the first to suffer the consequences of large-scale industrial activities. As the land of Indigenous Peoples is destroyed and resources made scarcer, preserving established cultural heritages becomes both increasingly uncertain and more essential than ever.

Burga’s work with Nuna Awaq is about respect—not only for the clothes, methods and materials that these Peruvian communities continue to use—but also in terms of establishing a clear framework for the fashion industry to avoid exploitation. Through Nuna Awaq, Burga works to ensure that brands are being honest in their intentions when seeking to work with artisans and textile weavers in Peru.

“The issue with brands [is that they] frequently run campaigns in Peru, in Mexico, and [wherever] everywhere there are artisanal communities. They give these artisans 5 dollars, 20 dollars, for a [large] campaign that ends up in [say] Times Square and is [published] in various magazines. Nothing protects these workers—no system ensures that brands are conducting a fair business model for artisans and their workers. There isn’t a comprehensive one that protects artisans in this regard,” says Juana.

“With Nuna Awaq, we are creating a registry that helps [address] this issue…working globally, we connect with a lot of brands and designers [to discuss] how they work. If they have a sustainability label, I ask them about their process and the impact their work will have on the communities they [want to] work with.”

Nuna Awaq only endorses brands if they can prove this to be the case. If brands fail to present clear evidence that they are treating artisans and their communities fairly, then support is withdrawn. By using her platform and foundation, Burga and Nuna Awaq are paving the way for a more sustainable and just future for Peruvian textile workers and artisans. The task is not just to protect weaving practices rooted in ancestral tradition, but also to preserve their future.