Cristina Moreno launched Ōmbia Studio in 2020, creating handmade sculptural ceramic objects, from coffee and side tables, to planters and vases. What is distinctive about Moreno’s designs is their rustic quality – each object is unique by virtue of the marks left in the process of making. These imperfections that are characteristic of Ōmbia Studio are inspired by Moreno’s love of objects that have a quirk to them. “I’m drawn to things that are a little imperfect,” she says – speaking over Zoom from her home in Los Angeles – “it just makes something more relatable table than a [perfectly-square] wooden table. I connect with an object a lot more when you see that the wood has a split or a dent, or something like that.” Moreno says that she was first drawn to clay because of its meditative qualities, because it’s a slow material to work with, in the sense that it requires time and patience.

For Moreno, the process of launching Ōmbia Studio was an organic one. Previously working as a footwear designer, the foundations for the studio were laid after enrolling in a ceramics class. Though she quickly realised that ceramics was her forte, the class-based approach was not, so Moreno began experimenting with clay straight away to create homeware objects. Furniture pieces that Moreno designs through Ōmbia Studio includes a series of “slab” tables, the name of which comes from what she describes as the act of dropping clay and seeing how it forms. More recently, Moreno has started researching for a new collection of items, which will move away from working primarily with ceramics. Here, Moreno discusses the organic process behind making her sculptural pieces for Ōmbia Studio has developed in the three years since it was launched, and where she draws her inspiration from.

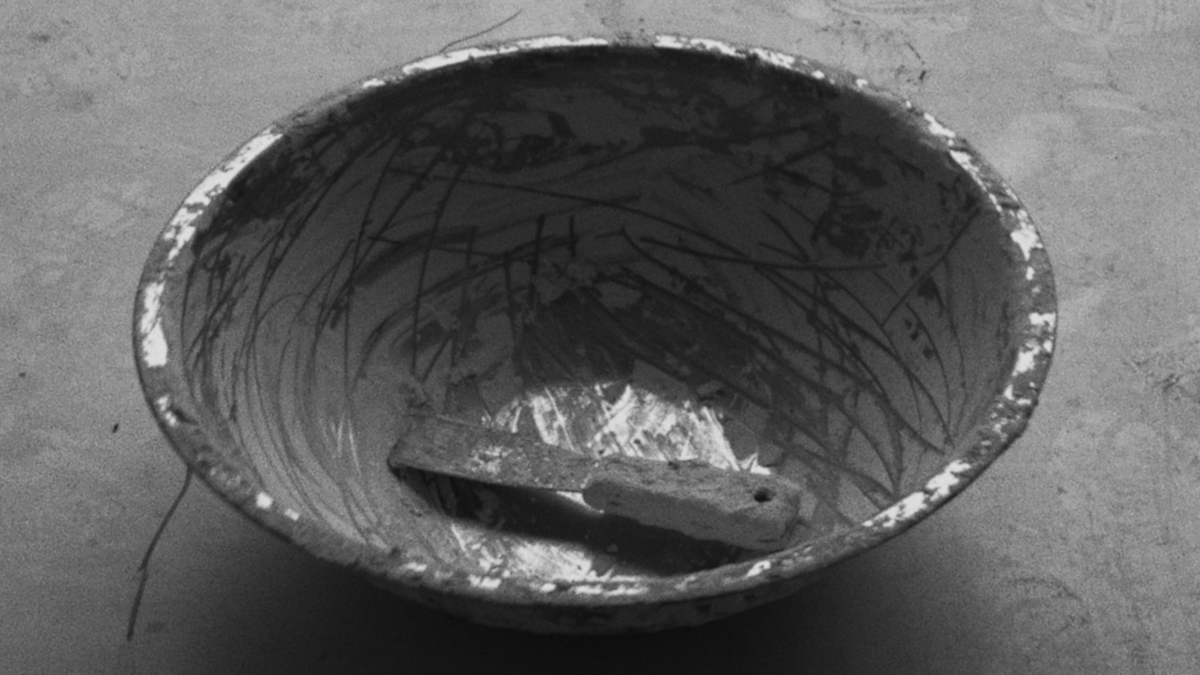

It’s been very organic. It started out of wanting to do something manual again. I was a footwear designer before working [digitally] a lot, and I knew I wanted to step away from that and start building with my hands. I started taking a ceramics class but I quickly realised classes [weren’t for me] as I didn’t want to learn the technicalities, but just explore the material on my own. So I got a membership and just started playing around and exploring – pushing the limits of what the material could do. I started with vases, because that’s what your brain immediately thinks of with clay. I tried plates. I tried so many different things, always trying to make something different and push the material.

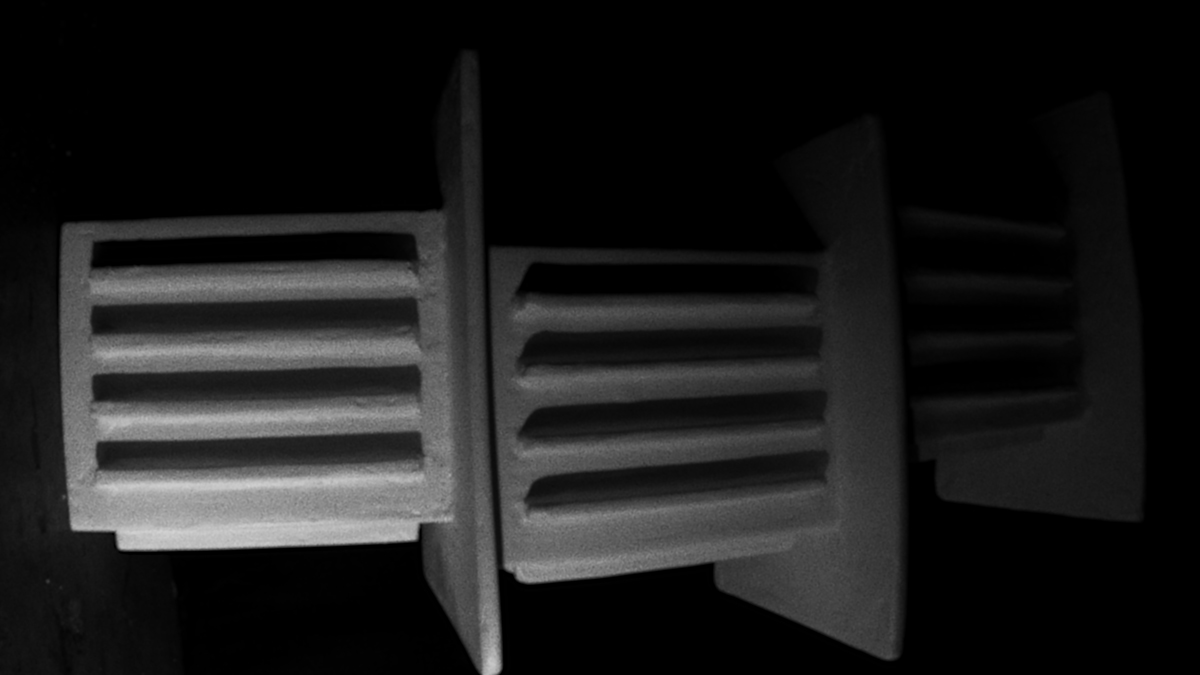

And then I ended up making little tables and little pedestals. I couldn’t go much bigger than that, because of the kiln size – but I [wanted to find a way] to recreate my small tables on a larger scale. So I developed this material that looked like clay that I could go as big as I wanted with no constraints; there was no breaking in the kiln, [or] firing it too high and the glaze dripping. There are so many problems that come with clay at that scale, so it was really nice to have more freedom to explore larger objects.

I really let the process inform my decisions and that’s something I learned by working with clay. You can’t really control it and you kind of have to let it do what it has to do. I would pass the clay through the roller and it would create these shapes – instead of cutting it into a certain shape I would just let it be. And so, I wanted to bring that into the [design of] tables. I mould the edges of the tables by hand, and you can see the thumbprints all over it when you look closely. When we were shooting the video for Present Space, David the videographer, was shocked by how manual the process is – he didn’t think there would be so much sculpting of the table legs!

Yes, there is definitely a distinction between these, but for me that doesn’t really matter. It was really important to me that the objects I created were functional. Coming from a textile and footwear design background, there has to be a purpose – I want people to use and enjoy [the object]; I want people to interact with it. And I want to understand how someone puts a glass on it or finds use to it. So I knew that whatever I ended up designing it had to have a purpose or a function to it, that is really important. But aesthetically, it could also be an art piece – something that you’re able to admire, be intrigued by, and form a connection, especially when you can feel that someone hand made it, I think that’s beautiful.

There are different reasons, but I think the main reason was to push the boundaries and understand how far I can take the material. It started with a table that was this big [miming a small side table], to making an 11-foot long dining table. You really have to get the structure right and solve a lot of issues from going from something [small] to something so massive. That challenge is really thrilling and exciting.

Yes, a lot! Sometimes I needed ten guys to help me flip a dining table – I built the tables upside down first, and then needed to flip it…

Never. This is why, when you ask me how I got where I am today, I say it’s been organic. And I think the main [goal] has been to remain organic, in every sense of the word – with the shapes, with the business model, with everything. I’ve really stuck by that and let it kind of unfold on its own. I never want to put too much pressure on it [and] just see where it takes me. In terms of the design, not one thing is perfect. Even with the rectangular tables that look a little bit more “perfect”, if you look closely, there is something crooked or imperfect. I’ve stuck by that, and I love that.

“I think there was a loss of identity, and I’m trying to connect with that more and bring that into my design”

It’s interesting because [the roots of what I’m doing] stem my childhood – growing up I would also be sketching objects that I loved. That’s informed where I am today. And I think that, in the future, I want to keep exploring that, and building on that, playing with materials and challenging myself. I want to connect more with my roots that I’ve [often] fought to erase. I was born and raised in Colombia but my mom is German/American, so I grew up multi-cultural. I think there was a loss of identity, and I’m trying to connect with that more and bring that into my design. “Ombia” comes from Colombia and this wanting to connect with my country that I always was running away from – that I felt like I didn’t belong to. [Now], I’m kind of going back to that, and paying tribute to it.