Duane Michals knows how to tell a story. This is apparent to anybody who has seen any of his Sequences, in which a narrative—often verging on the surreal—unfolds over several photographs. Take Things Are Queer (1973), a series of nine images, in which a framed photo hangs in a bathroom, which transpires to be a miniature bathroom, and that miniature bathroom is actually a photograph in a book being read by a man walking down a dark alleyway—a photograph of which is the hanging frame in that miniature bathroom. The stories embedded with Michals’ work are often only partially told. In the six photographs that compose Chance Meeting (1972), two men cross paths, turning back to look at one another after passing by: it is unclear what their relationship (if there is one) is—strangers, a familiar face?—but the sequence seems to be loaded with meaning.

As the French philosopher Michel Foucault wrote of Michals’s work in 1982, it evokes “an encounter that has no future, an irrational anxiety in a familiar street, the sense of a strange presence nobody else believes in” but ultimately, he adds, these are encounters that “no one but he had, but which, I do not quite understand how, glide towards me—and, I think, towards anyone who looks at them—evoking pleasures, anxieties, ways of seeing, and sensations I have already had or I anticipate having to feel on day, and therefore I always wonder if they are his or mine, although I know very well that I owe them to Duane Michals.”

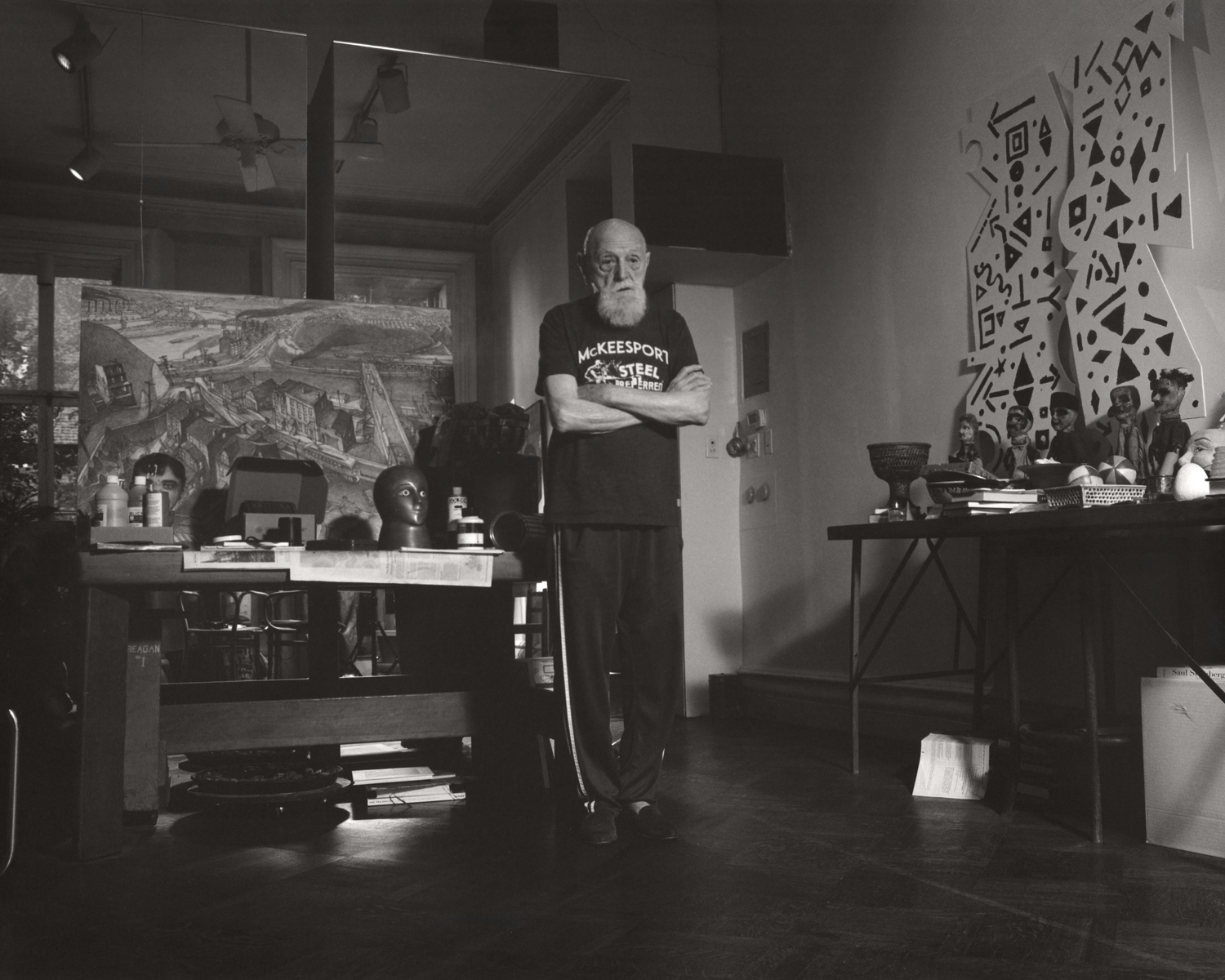

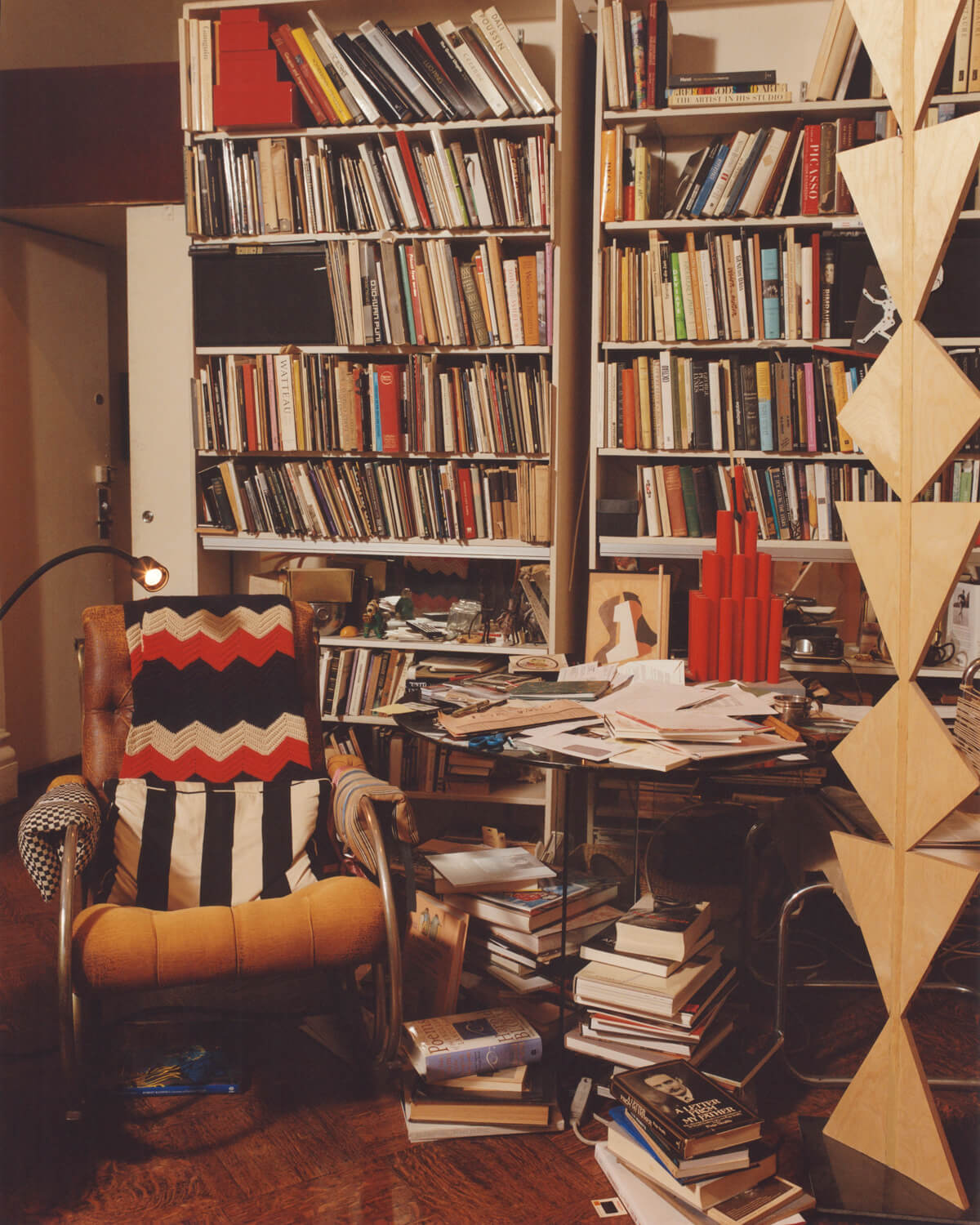

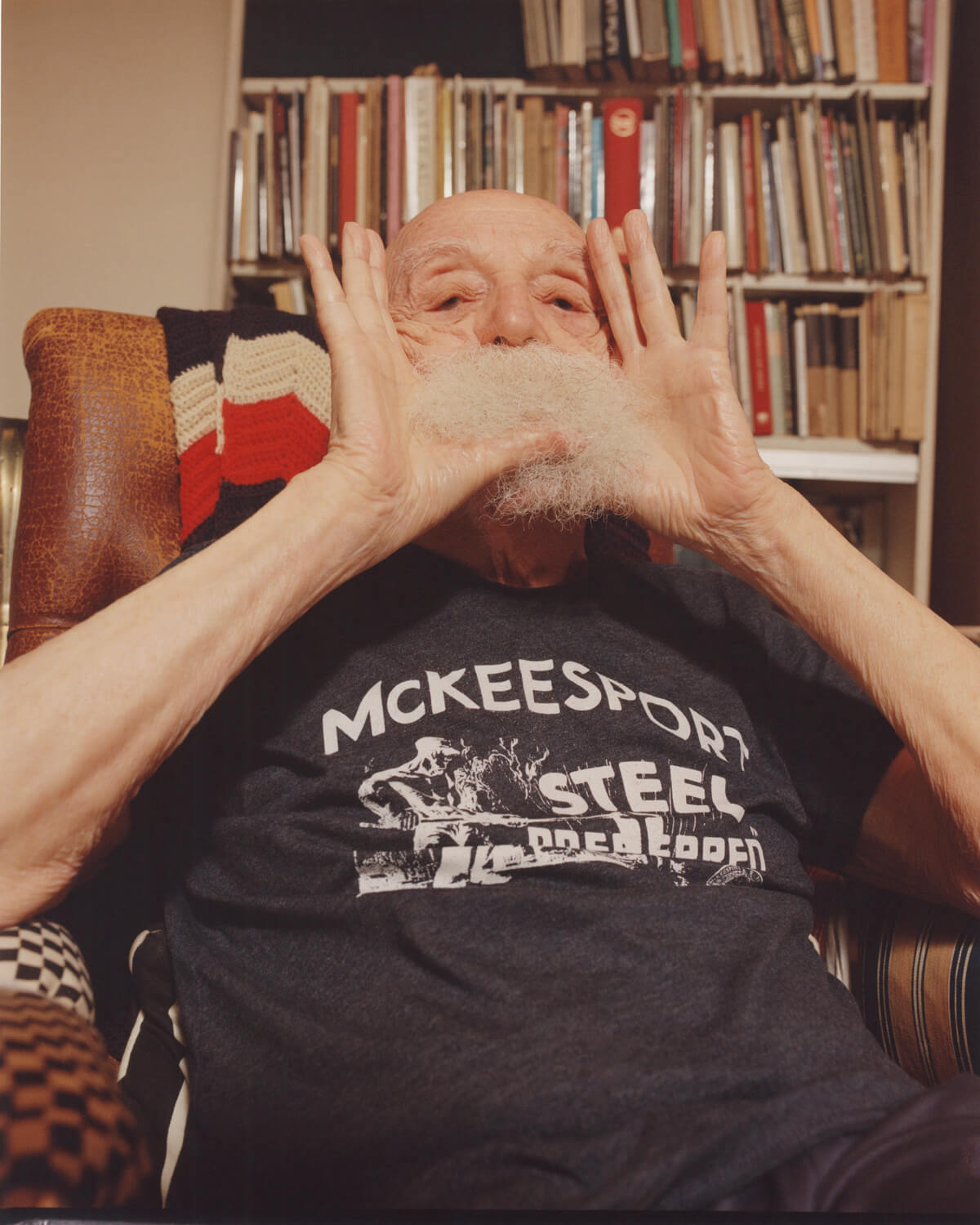

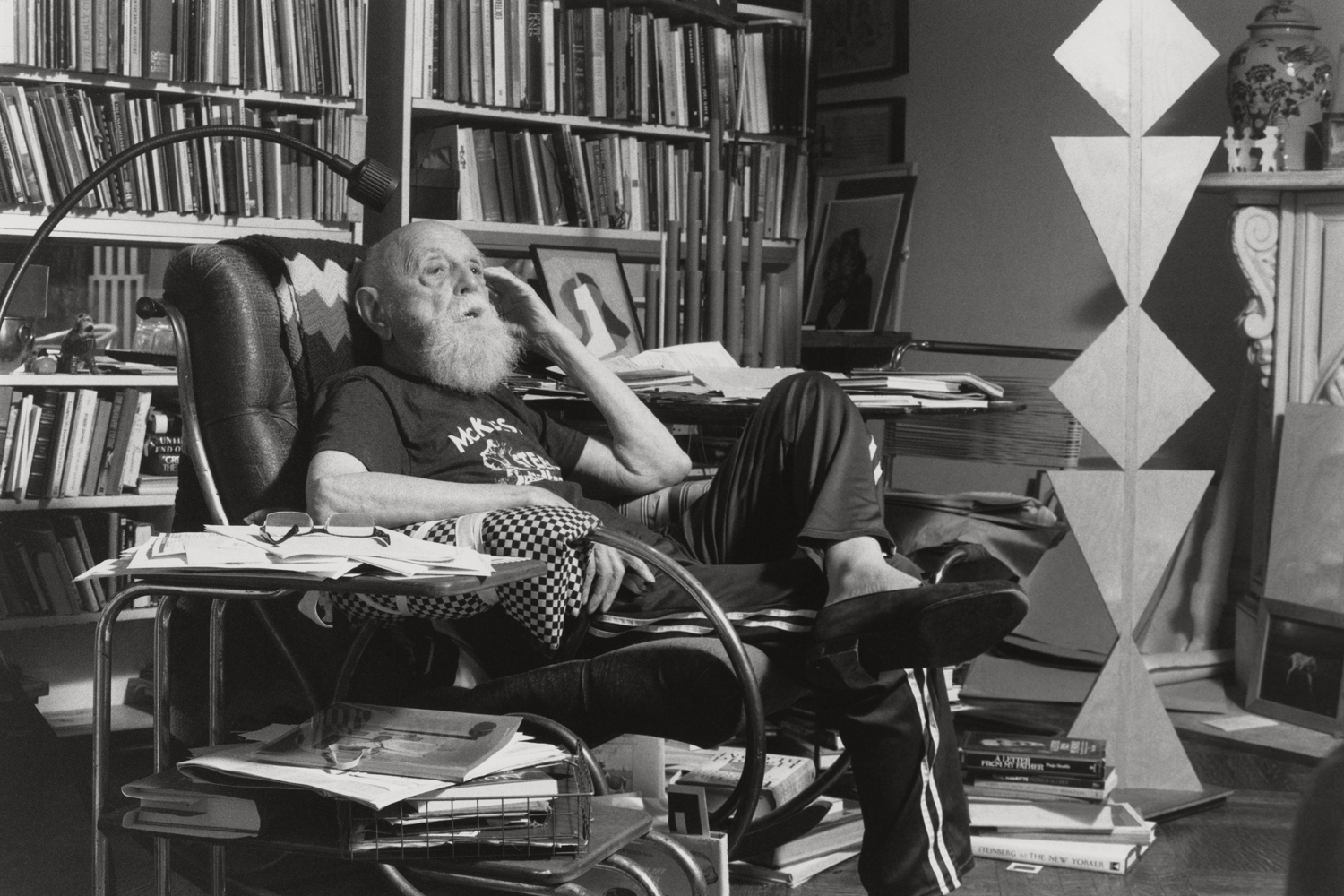

Michals, 92, is no stranger to sharing his experiences, his stories, as I find out over the course of a phone call from his New York studio. In fact, the photographer illustrates many of the points he makes in response to my questions through stories, encounters and photographs that he has taken. For example, Michals strongly rejects the idea that you can capture the essence of somebody: to illustrate this point he brings up a series of close-up portraits he made of Tennessee Williams in 1966 (in one, the actor’s face is blurred as he turns away—or toward?—the camera). Of this, Michals recalls, “I went to photograph his apartment. He was so high that he didn’t even know I was there, and I just leaned him against the wall in the kitchen, you know, high as a bat or whatever. That’s who he was. I didn’t capture anything.”

He raises this point because he is critical of how images can be taken as fact: a tired-looking Marilyn Monroe looking away from photographer Richard Avedon’s lens—“that doesn’t expose her soul”—or, the story that Yousuf Karsh snatched Winston Churchill’s cigar in the moment before photographing the prime minister with a snarl on his face: “I doubt very seriously that…in the presence of Churchill, he would have the balls to pull the cigar out of his mouth”. This might seem at odds for someone whose photographs are recognised for their often complex emotions.

But to be clear, it is not the notion of presenting feeling that Michals critiques, but a seriousness that photography bestows onto itself. “All those claims, I think, are embarrassingly vulgar, to say that you took a picture of somebody, and you revealed them. That’s total nonsense. Really, it’s hyperbole.” Michals’s dislikes are well-documented: he is not keen on street photography: “there’s no invention, there’s no editorialising”. Nor is he a fan of photography as an art form—see Who is Sidney Sherman? (2000) or A Gursky Gherkin is Just a Very Large Pickle (2001) for witty, unsubtle takes on some of the targets of Michals’s ire.

Ever since he started out as a photographer in the late 1950s, Michals’s work has radiated with an irreverence and a playfulness such as in Self-Portrait as if Were Dead (1968), in which the photographer, crossed arms, looks down at himself, on an embalming table. This playful approach has lent itself to taking portraits of everyone from Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp to Shelley Duvall, Joan Didion and a young Meryl Streep. Of photographing the latter in Times Square in 1975, Michals recalls, “we were just running around and her vigour and her youth and her spontaneous combustion occurred. It’s a picture of a beautiful young woman and her energy exploded.” Rather than claiming to capture the essence of his subjects, Michals takes a portrait as if it is in the “manner” of the person. In 1966, for instance, Michals visited René Magritte at his home to take a series of portraits of the surrealist artist: in one image, Magritte dons an upside-down bowler hat on head, not unlike the kind of bowler hat that appeared in many of his paintings. If not evoking Magritte’s inner-self, it’s an image that speaks to Michals’s adept at turning photography, playfully, on its head.

Most photographers have somebody fit their style, but I love to work in the manner of the person. When I photographed Magritte, the pictures were in the manner of what Magritte would have done…if he had been a photographer, he might have taken photographs that look like that. I took a picture, which I really liked, of Tilda Swinton…and she’s wearing this suit, but she’s wearing it backwards. So, what you see is a person wearing a suit and tie, but their head is facing backwards. And she is holding a mirror, and so although her face is backwards, you can see her face in the mirror. It’s a picture of her in the manner of Tilda Swinton, the great actress who has played many parts and many roles. You see her, but you see her in her character, as an actress.

I mean, at that point I’m probably onto something else. I’m very productive and I do a lot of things. So, if I look at something later, I’m always anxious to see if it worked, if the concept works. And sometimes I think, “This should have been better,” but I’m my own worst critic.

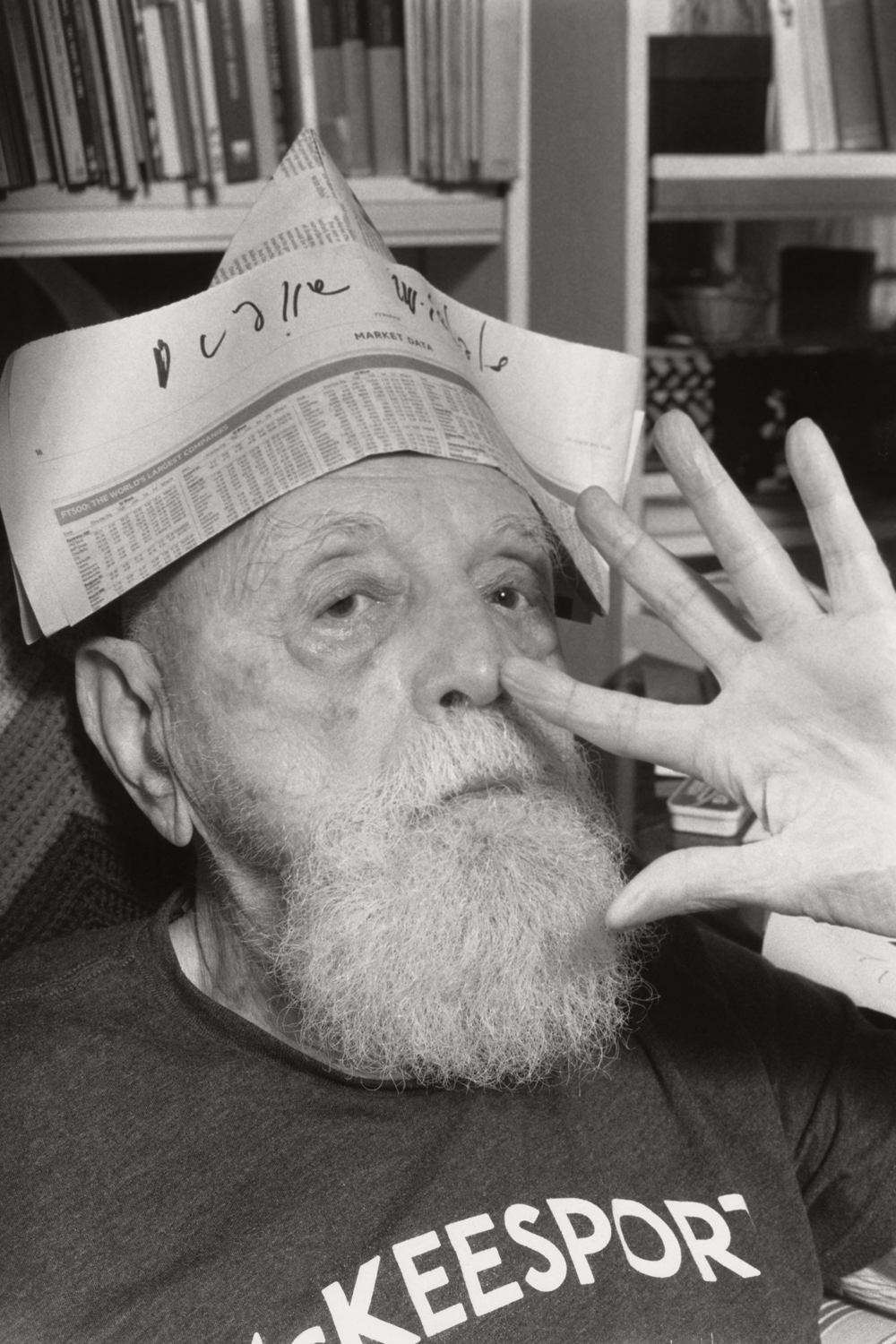

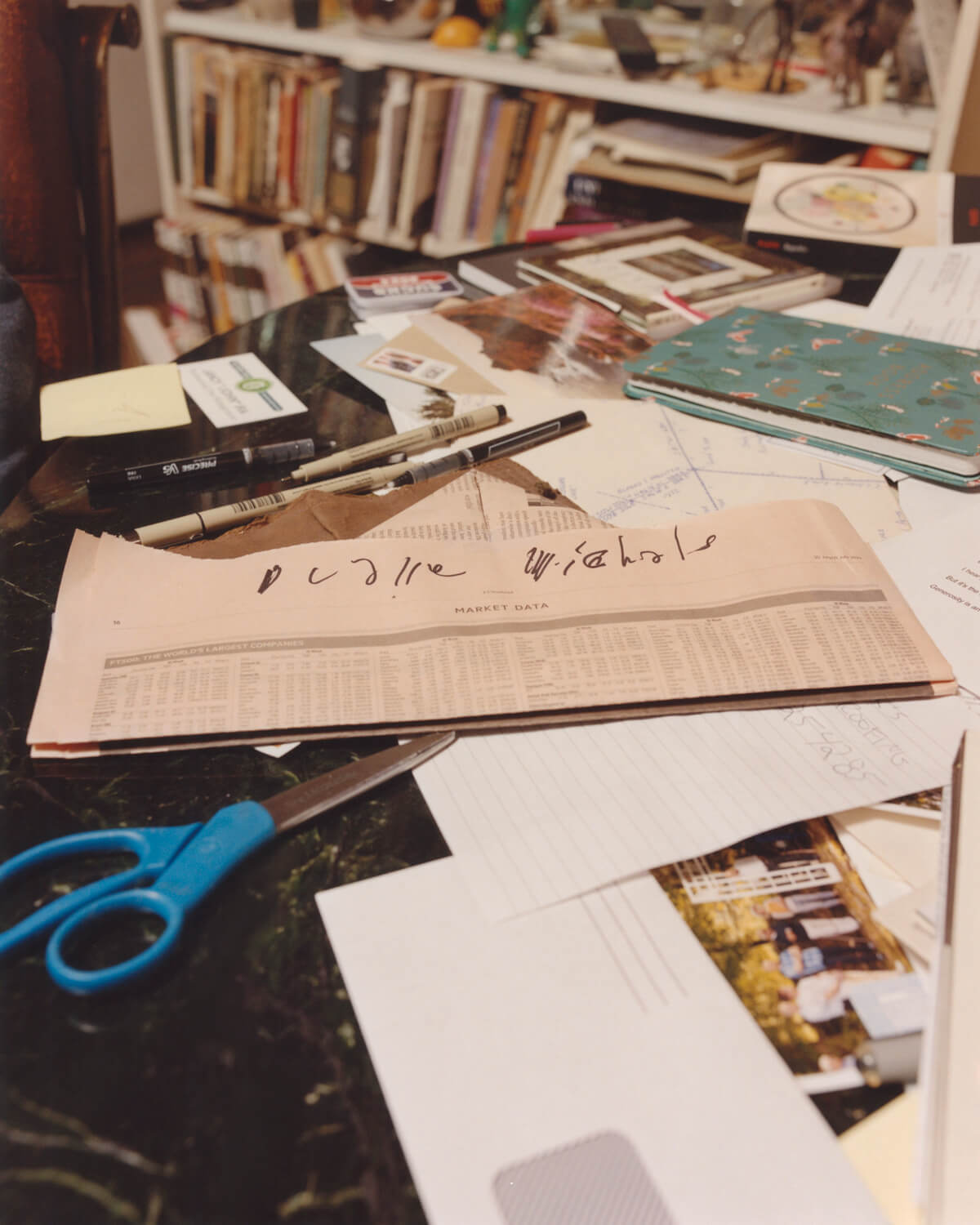

I didn’t have any other choice… In Self-Portrait as If I Were Dead (1968), you see a table and you see me laying on the table with the sheet and my eyes are closed. I thought [it was] very reasonable, but for a lot of people—I mean, I don’t know of any other photographer who would do his self-portrait if he was dead. [But] I didn’t take the traditional route. I always did what I found amusing, or contradictory, or fun. You have to be light-hearted, and I’m light-hearted about everything, and goofy. And now that I’m really old, I’m goofier than ever.

I use all the vocabulary of the camera. When I first went to Russia [in the late 1950s], my cheap Argus C3 double exposed. I was photographing this guy and then I looked at the picture and I thought, “Well, that’s interesting.” I didn’t think, “Oh, I fucked up—I double exposed!” I thought, wasn’t that great. That’s what the camera does. I use all vocabulary in the camera: time exposures, blurs, you

know, and I found it more and more liberating. Most people like the perfection of the camera, but I like the flaws….I’m an expressionist.